Man who shined light on Las Vegas’ tunnel dwellers moving on

The afternoon sun hammers hard as Matthew O’Brien approaches the entrance to the storm-drain tunnel, this solemn gateway to a subterranean netherworld inhabited by living things — insects, animals, even humans.

He pauses at the mouth of the twin shafts that run beneath the south end of the Las Vegas Strip, standing inside a concrete culvert littered with beer cans, plastic bottles, cigarette butts and a tangle of soiled blankets as traffic whizzes past just a few feet away.

He removes his sunglasses, dons a knit cap and peers cautiously into the abyss.

These first moments inside will be critical, before his eyes acclimate to the darkness. As much as he can, he wants to know what — or who — awaits just beyond the weakening beams of daylight.

“It hits you as you look into the darkness,” he said. “At first, you’re not sure whether a tunnel goes across the street or for 6 or 7 miles. Before you step inside, you’re nervous, on edge. You don’t want any drama right away because you’re blind. Even after your eyes adjust, sometimes you have to summon the nerve to keep going.”

O’Brien, 46, isn’t any sanitation worker and he isn’t a cop. He’s a former journalist who since 2002 has embarked on a project to plumb the 250-mile-long network of underground drainage tunnels that run beneath the Las Vegas Valley like murky arteries or godless catacombs.

What started as a magazine writer’s daredevil foray into the unknown soon became something more: an unlikely urban outreach. As he inched through the gloom with a flashlight for guidance and a golf club to fight off the sticky spider webs and plumb the depth of running water, O’Brien discovered that the tunnels are home to a complex human subculture with its own rule-of-law.

Denizens of the dark

There in the depths, often lurking directly beneath the lavish casino gaming salons on the surface, an entire community of castaways has turned the tunnels into makeshift domiciles that range from sleeping bags tossed onto the concrete to makeshift bedrooms featuring painted walls, lighting and queen-sized beds propped off the floor with milk crates or shopping carts.

These residents, many fighting addictions, bad decisions and skeins of rotten luck, seek out the darkness, enduring the vermin, bacteria and the occasional flash flood as a way to escape the heat and police harassment. O’Brien estimates some 300 people call the tunnels home.

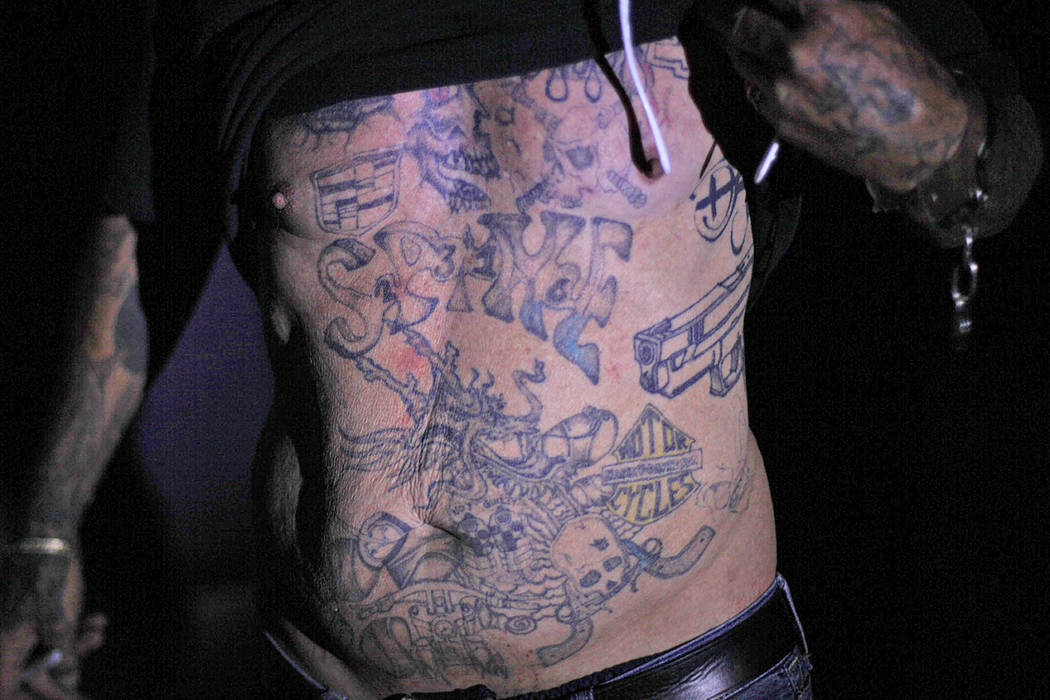

There’s John, a former Florida bar owner who after seven years here considers the tunnels a respite from the “real world,” the demand to “pay bills, pay bills and pay bills.” There are residents who read by flashlight, or relax on chaise lounges in the darkness. And there’s Spike, a rangy 62-year-old with a constellation of tattoos, a Mohawk and a wrist-ring handcuff he wears as a bracelet.

In 2002, O’Brien co-wrote two stories on the tunnel culture for the Las Vegas CityLife alternative weekly, traveling underground with a journalist companion who carried a Samurai-sword-like knife. But after the stories were published, something drew O’Brien back into the dark. This time, he went in alone, carrying his tape recorder and flashlight to conduct further research into the hard lives and predicaments of these often-destitute tunnel denizens.

He eventually published the book “Beneath the Neon: Life and Death in the Tunnels of Las Vegas.” He believed the broken lives portrayed in the book would bring concrete results, good or bad — either a dreaded police crackdown of the tunnel subculture or a renewed outreach there by social service agencies.

Neither happened. So O’Brien founded the nonprofit Shine a Light, which collects and distributes food, water and other necessities for the people living down under. Fifteen years later, he is still going back, no longer as a journalist, but as someone tending to the needs of people he now considers friends.

On a recent afternoon, O’Brien cautions two other tunnel visitors to wait while he steps inside the gloom. After so many years, he takes such precautions not as much for his own safety but as a concern he might be invading someone’s privacy.

O’Brien walks into the shadows and extends a hand to a man named Gordon, a Pennsylvania native who has called these tunnels home for four years. The temperature inside is 20 degrees lower than the sweltering weather outside.

“Hey Gordon,” O’Brien says, his voice light. “How’ve ya been?”

The man takes the question literally, dropping his shoulders heavily.

“Not good,” he says. “My back’s really bad. Some days, I find it hard to even move.”

Gordon is 56, “but I feel like 76.”

O’Brien lowers his backpack, rifling its contents for hand-outs. He keeps up a steady patter of conversation, raising his voice over the roar of departing jets at the nearby airport.

He offers Gordon a snack-sized package of Pop Tarts. Sensing hesitation, he quickly includes a bag of Goldfish crackers.

“Everybody likes Goldfish,” O’Brien says.

Las Vegas Review-Journal

His offerings include socks, underwear, shampoo, deodorant and bottles of water. Gordon extends an unsteady hand, gnarled and blackened from a life both above and below ground.

“What’s new down here?” O’Brien continues.

The two talk briefly about such colorful residents as a man known as “the Mayor,” as well as those who have moved on from the tunnels. As he talks, O’Brien slips Gordon a $10 McDonald’s gift card, re-shoulders his backpack and moves deeper into the darkness.

Life underground

O’Brien is parts urban spelunker, psychiatrist and tour guide; he’s someone who readily interprets the environment at the end of his flashlight beam. As he walks, his 6-foot-3 frame bends slightly to accommodate the tunnel’s low, rounded ceiling. After so many visits, he knows to walk in the tunnel’s center where spider webs and their makers are less likely to make one’s skin crawl.

Like a summer counselor around a campfire, he lists the tunnel’s nonhuman inhabitants he has encountered: rats, mice, stray cats, strangely glowing crawfish, cockroaches and once, a spider “the size of a Volkswagen.” He once heard a rumor that mountain lions sometimes entered the tunnels in search of food.

His book portrays the realm as a metaphor for the dark state-of-mind that brought many residents here in the first place.

“If (these walls) could speak,” he wrote, “they would tell startling tales; tales of addiction, desperation and madness; of loneliness, love and regret; of triumph, disappointment, and, yes, death.”

The writing is evocative, describing a place that “had no air, no sound, no light. It was as still and dark as the inside of a coffin.” He tells of clutching his flashlight and entering one tunnel “with the uneasiness of walking into the barrel of a gun. I was ambushed by darkness. It flowed along the floor, walls and ceiling like floodwater.”

On this day, O’Brien pauses, shining his light on a graffiti scrawl. He’s seen phrases from Yeats, Conrad and Milton, all penned by down-and-out denizens of the deep pondering the fate of mankind. This one is personal, even revelatory. “I think of myself as a sensitive intelligent human,” it reads, “with the soul of a clown which forces me to blow it at most important moments.”

The tunnel guide shakes his head: “There’s something about the tunnels — maybe it’s the drugs or alcohol — that turns people into philosophers.”

Dangers down under

In the dark, he senses a figure ahead. He calls out, observing one of the unwritten rules of the tunnels. Encampments are considered people’s homes; you don’t just blunder through them. You first ask permission, and if no one is there, you turn around rather than trespass.

There are other dangers. Flash floods can wage surprise attacks, leaving tunnel residents to scramble up ladders to avoid the torrents, or toss their belongings into a shopping cart for a fast getaway. On this day, a basketball, soccer ball and several golf balls tumble past, presumably deposited here by a recent tide of storm water. O’Brien also has encountered an iron safe, oxygen tank and even an automobile swept into the storm drains by the relentless current.

He points to a water mark on the tunnel wall to demonstrate just how high flood waters rise down here, warning that the torrents can rise a foot per minute. Once, a tunnel resident rode his mattress on a black wave of water until he reached sunlight. Last year, a flash-flood surprised a number of people inside this tunnel, including a couple named Jazz and Sharon. Jazz survived, but Sharon’s body was found a mile downstream. She was one of three tunnel-dwellers who drowned that day.

Tunnel vision

O’Brien first descended into the tunnels on the heels of a rapist and murderer.

In April 2002, something snapped inside Timmy “T.J.” Weber: He killed his girlfriend and one of her sons, and raped her 14-year-old daughter before going on the run, seeking shelter in the drainage ditches beneath Las Vegas.

Las Vegas Review-Journal

Curiosity drew O’Brien to follow in his footsteps after Weber’s arrest and later conviction. “I wondered what Weber experienced in the storm drain,” he wrote in the introduction of his book. “What he saw, what he heard, what he smelled. How, apparently without a light source, he’d splashed more than three miles upstream. Did clues of his escape route remain? Could he hear the police dogs howling overhead? The sirens screaming?”

And so, O’Brien writes, he grabbed his tape recorder and went in. “I pressed ‘Play’ and ‘Record,’ snapped on the flashlight, and followed him.”

At the time, O’Brien was the managing editor of CityLife, so he assigned the tunnel story to contributor Joshua Ellis and tagged along as a reluctant observer as he searched for his tunnel legs. Together, the pair charged into the underground space. Ellis wore a trench coat, knit cap, head lamp and combat boots. He carried an 18-inch curved knife “that could gut a shark.” O’Brien wielded a 7-iron.

Colleagues at CityLife thought the pair had lost their minds.

“I told Matt, ‘You’re gonna get killed,’” recalled Jarret Keene, who edited the pair’s tunnel series. “I was scared for him. We were all concerned. We thought it was kooky.”

Even after the stories were published, O’Brien returned to the deep to continue research for his book, this time replacing his golf club with an expandable baton.

Turning point

The journey helped turn him into an activist.

“He never struck me as someone who was particularly activist. But he’s done an incredible amount of good in the last decade and a half,” Ellis said.

“Beneath the Neon” was published in 2007, setting off an international media interest in the people of the tunnels. Television, radio and print reporters flocked to Las Vegas for an excursion into the storm drains. An art exhibit based on O’Brien’s findings was staged downtown.

“One of the reasons the subject received as much attention was the irony of having this dark and gray underworld existing right below the bright lights of the casinos,” O’Brien said. “If I had explored the tunnels below, say, the city of Atlanta, it would not have had the same appeal.”

But O’Brien did not flaunt the tunnel dwellers for his own ends. He only escorted journalists with the legitimate goal to publicize the strength and resilience of people who lived there. And he encouraged them to make a contribution to assist in their cause, just as he was doing.

Into the light

Word has spread throughout the storm drain community: O’Brien is leaving Las Vegas.

After 20 years here as an writer, editor and teacher, he’s moving to Central America to teach and to write. One of the toughest parts of the move, he said, is walking away from the tunnels. But O’Brien is working on a parting salute to the people he has met there. He has recruited volunteers to continue his “Shine a Light” outreach. He is also at work on a sequel to “Beneath the Neon” to tell the stories about the survivors who have walked out of the darkness and into the light.

“I want to tell an inspirational story about people who made it out,” he said. “It’s an oral account of the people who have survived the storm drains.”

He has interviewed nearly three dozen former residents, people like Bill Richardson, a military veteran who is now working under the Texas sun.

“That’s my bro right there,” Richardson said of O’Brien. “He climbed down the ladder that led to the tunnel where I lived. And then he saved my life.”

Cynthia Goodwin also once lived in the Las Vegas storm drains. Now she works at a rehab center in Texas: “Matt didn’t have a lot of money. Sometimes the things he gave us came out of his own pocket,” she recalled. “He was the only person who treated us like we were human.”

Rick Ethredge, Goodwin’s partner, said O’Brien’s kindness showed him how to start a new life as an addiction counselor in Texas. “He restored my faith in humanity — I had completely lost faith in people,” he said. “The only way I can repay Matt is to help people in the same situation I was in. Matt showed me how to do that.”

Now the name Matthew O’Brien has joined the graffiti-therapy inside the Las Vegas storm-drain tunnels – written by a departing longtime resident giving thanks to the people who helped him survive the dark until it was time to emerge into the daylight.

John, the former Florida bar owner, lies in his sleeping bag, resting up for his graveyard shift job at a convenience store. In a croaky voice, he says he’ll miss the man who after seven years has become his friend.

“Matt has definitely brought a little help to the people of the tunnels. He’s brought us all a little sunshine,” he said.

Award-winning journalist John M. Glionna, a former Los Angeles Times staff writer, may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com. Follow @jgionna on Twitter.