Prospectors search for denim gold in old Nevada mine shafts

SULPHUR — The two amateur prospectors moved along a rocky hillside in the wooded wilds of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, picking their way across an unyielding landscape studded with juniper trees and pinion pines.

They were looking for holes in the ground.

Finally, they spied what they’d come for — an abandoned mine shaft whose tiny, jagged mouth was gouged into the side of a rock wall that flashed a signature of iron and copper. The men flushed with the excitement of archaeologists encountering a Pharaoh’s tomb, anticipating the riches that might be found inside.

But it wasn’t gold or silver they sought. It was blue jeans, the remnants of old denim work clothes — shirts, trousers, jackets and coveralls — worn by the countless grizzled veterans of the Comstock Lode, men who plied this same ground with picks, axes and caches of dynamite some 150 years ago.

Caden Gould, 41, a handyman and adventurer dressed in an old pair of Wranglers, flannel shirt and scuffed boots, set down his can of Coke and considered the task before him. He knows the most dangerous part of any mine excursion comes in the first 15 or 20 feet, where the exposed rocks and crushing boulders looming overhead are most likely to break free and come tumbling down on top of him.

Ron Bommarito is Gould’s sidekick and neighbor from the nearby town of Genoa, an antique dealer who at age 70 is old enough to be the younger man’s father.

He sensed his hesitation. “OK, so get in there,” he deadpanned.

Turning on his headband flashlight, Gould slid onto his belly and wiggled into the tight chasm.

Soon, only the soles of Gould’s boots were showing. Then he disappeared entirely. “This is where you get killed,” he muttered.

‘Iconic Americana’

The unlikely duo has formed a rustic brotherhood of historic pants, joining a handful of vintage-denim hunters who plumb abandoned mines across the West looking for the mother lode of denim.

They’ve searched the back rooms of old hardware stores, plumbed retired outhouses, scoured the crevices inside aged barns and once found a pair of old denim lying right there on the desert ground near the town of Mina, dyed white by the sun and alkaline crystals growing out of its seams.

But most blue-jean booty lies underground, inside often-forgotten mines spread across the Silver State, with names like the Ben-Hur, Silver Pick, Marble Monster and Sage Hen. Most wooden-ribbed shafts and crawl spaces they enter have no names at all, or if they did, they’ve been lost to the mounting dust of time.

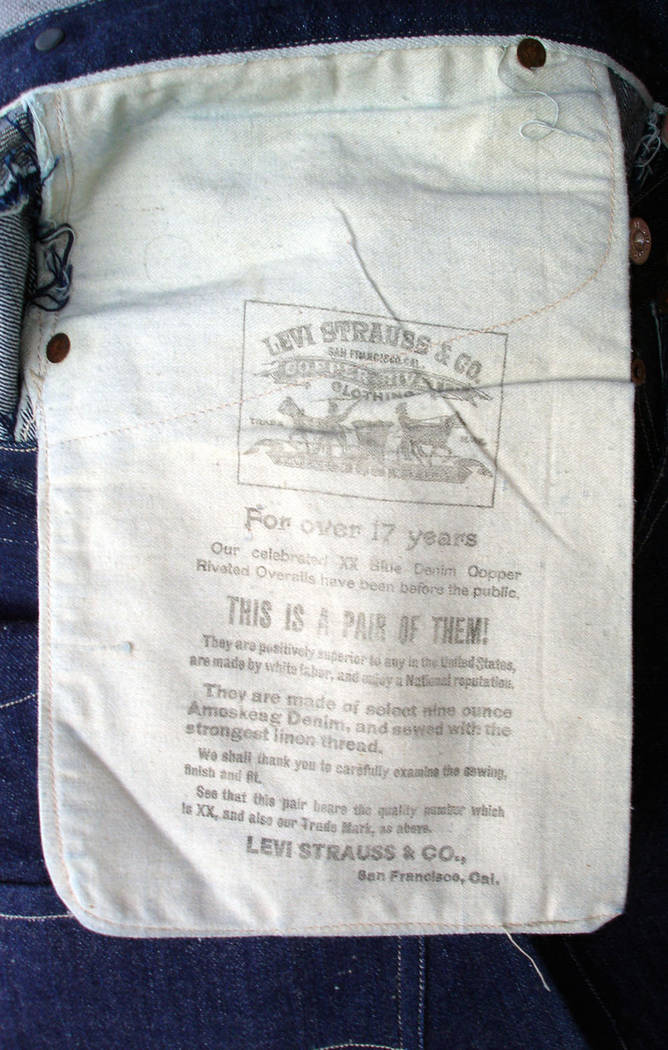

The pair pursue the holy grail of vintage denim — the line of apparel patented by entrepreneur Levi Strauss and Reno tailor Jacob Davis in 1873. The corners, rivets and pockets made the dungarees the sturdy favorites of not only miners, but also loggers, farmers and cowboys across the American West.

For the lucky finder of a vintage pair of Levi’s, the payoff can be princely.

Vintage denim is big, according to Daniel Buck Soules, president of Lisbon Falls, Maine-based Daniel Buck Auctions and a regular on PBS’s “Antiques Roadshow.”

He should know. Earlier this year, a pair of Levi’s denim jeans originally purchased in 1893 by a dry goods store owner in the Arizona Territory sold for nearly $100,000, through Soules’ auction house. The cotton jeans with a 44-inch waist and a button fly had no belt loops because most men wore suspenders back then.

“People all over the country are coming to me with pairs of Levi’s to sell. We have 15 to 20 pair coming up in our spring auction,” Soules said. Among the items at that auction will be a rare pair of child’s overalls from the early 20th century, he said.

Why are people so willing to shell out six figures for a pair of blue jeans?

“In two words — iconic Americana,” Soules said. “It really comes down to the fact that nothing says ‘America,’ especially to people in Asia, like a pair of Levi’s.”

The brand — and some of the jeans — have stood the test of time.

“There is a huge history to this apparel, from mining to its role in pre-earthquake and pre-fire San Francisco at the dawn of the 20th century,” Soules said. “When you say the word ‘Levi’s’ anywhere in the world, people know exactly what you’re talking about.”

Soules has been involved in the sale of more than a dozen pair of vintage Levi’s but has never bought apparel from mine searchers like Bommarito and Gould.

Buyers of old jeans, many from Europe and Asia, include curators from Levi’s own company museum in San Francisco as well as high-end clothing designers such as Ralph Lauren, who repurpose the material into modern apparel. Twenty years ago, Levi’s even launched a vintage clothing line that featured replicas of recovered pieces — including those with holes in the legs and without pockets.

For many, the vintage jeans scream out with the colorful history of the Old West.

Many hunters who come across vintage jeans call the Levi Strauss company in San Francisco for assistance in pertaining their value.

Demand became so high that Levi’s historian Tracey Panek has a telephone voicemail greeting that points denim finders to websites such as Denim Hunt and Denimology. And watch eBay, she advises — the selling prices there will help determine value.

Gould and Bommarito have yet to find their pot of gold at the bottom of a tunnel.

Bommarito found his first pair of vintage denim in the 1970s and has since sold numerous pairs for a few thousand dollars or more. A veteran antiques picker with a major collection of Nevada artifacts, he has the low-key humor of an aging Bill Murray. He’s intellectual, a storyteller, who plumbs not just for denim but any artifacts from the state’s territorial days, including a rumored lost box of gold plundered from an early stagecoach robbery.

“There’s all kinds of neat stuff out there,” he said. “Nevada’s funny that way.”

‘Addicted to denim’

Gould, whose ancestors ran the Gould and Curry Mining Company in 1860s-era Virginia City, grew up on his grandfather’s ranch before becoming Bommarito’s protege five years ago. Quiet, muscled, determined, he wields the energy of a settler who lived on the land 150 years ago, or a miner who went below it. He likes to repel deep into the shafts, going far lower than the amateur spelunker, where many of the denim finds lie, while Bommarito stands on the surface to offer sage advice via walkie-talkie.

Gould had traditionally looked for minerals, not clothing. “Now I’ve created a monster,” Bommarito said of his partner.

Gould said he once drank to excess, but denim has helped him overcome that crutch. “It’s the thrill of the chase,” he said. “It’s like the alcoholic chasing the drink. Now I’m chasing something else. I’m addicted to the denim.”

On a cool day in early autumn, the pair left Genoa just after daybreak in Gould’s 2002 Ford diesel truck with 600,000 miles on the odometer, two cracks that meander across the windshield, an ashtray overflowing with cigarette butts and a pair of binoculars stashed on the driver’s side floor. In the back was a case of dog food and, under the seat, a roll of toilet paper, which Gould calls “mountain money” because “it’s more valuable than any currency once you get up there.”

Before they left, he had completed hours of computer research, scouring various internet sites for tips on the mines they intended to explore — information that included the years of operation, total depth, production numbers and types of yields.

And, perhaps just as important, whether they’re already claimed.

DenimThe excavations are not for the faint of heart. More than 50,000 of Nevada’s mines pose public safety hazards, according to the state’s Division of Minerals. Risks include “falls down inclined or vertical openings; rotted, decaying timbers; cave-ins; bad air; old, left behind explosives; poisonous snakes and spiders; disease-carrying rodents; and bats that can occasionally carry rabies,” according to the agency.

Since 1971, when the state began recording mine injuries, more than one dozen people have been killed and many more injured exploring underground shafts. Gould and Bommarito have heard the ominous cracking of a mine’s wooden supports, climbed on rickety 150-year-old ladders, dislodged rocks that have fallen atop their heads, denting skulls. But what the denim prospectors fear most is poisonous gas.

Bommarito said the two follow a trusted rule-of-thumb: “If anything smells funny, you get the hell out of there.”

On the most recent hunt, Gould walked upon the mouth of a mine shaft that had been fenced off with a sign that warned to stay out, adding, “Thank you for being on my trail cam! Evidence is going to BLM at this time. Have a nice day!”

Gould knows that mine owners can be a prickly crowd. The internet is filled with videos taken by amateurs who go poking into already-claimed mines looking to pillage gold and silver.

Gould claimed his first pair of vintage denim after watching an online video he recognized was filmed in a Tonopah mine. He saw the relic hunter step over a pile of clothing he figured contained some denim, and later went back to claim his prize.

Now he and Bommarito know not to give too many details about where they hunt.

Otherwise, the pair admit to be being amateurs in their quest. They know falling rocks could kill them but rarely wear helmets and don’t want to spend the $4,000 for an air-quality meter.

At mine sites, tempers can flare. Bommarito once had a fistfight with another denim hunter right at the open mouth of a vertical mine shaft.

“We could have tumbled into that hole like in some cheap movie,” he said. “If it’s not that, God only knows what real stupid is.”

Outside one mine shaft, Gould stooped low to throw in some rocks.

“Snakes,” he said.

Added Bommarito: “Caden has become a snake connoisseur.”

A few years back, Gould was searching out a mine in central Nevada with Colorado-based denim hunter Bret Eaton. On a steep hillside, he felt an old wooden retaining wall give way beneath him and out rolled a ball of rattlesnakes that hit him in the leg before the creatures slithered into the sagebrush.

He’d left his shotgun back in the truck a half-mile away, so he called out for his partner to start throwing rocks. But Eaton thought he was kidding and stood on the crest of the hill laughing. “Every bush was vibrating with rattlesnakes,” Gould recalled. “There was so much sagebrush I couldn’t see them, but I heard those rattles.”

He said he finally scampered up the hill untouched but will never forget the encounter. Sometimes, though, the danger gives way to jaw-dropping up-close views of history.

The pair have encountered underground scenes of half-filled ore carts still on their tracks, dynamite-packed walls with blasting caps at the ready, long-dead candles burned down to their wicks, the dirt floor littered with Wells Fargo receipts — as though those miners of another era had just walked way momentarily for a coffee break.

“Those old miners worked hard,” Gould said. “I wouldn’t do it. It’s scary down there, even with all the modern conveniences.”

In the end, the day failed to yield any denim finds. The pair’s best hope was a mine they believe was staked just after the end of the Civil War, pointing out the date “67” burned into a plank of wood with an acetylene gas lamp.

Often, when a mine’s era is in doubt, they scout for discarded bottles — canaries that suggest a mine’s age. Finally, Gould called it quits on the search, saying he planned to return and rappel down into the mine system from another vantage point.

Earlier, the two wandered around the remnants of an old 1910-era mill, inspecting cracks the walls for any secret spaces that miners could have stuffed with denim to stop the incessant wind.

“Here’s some old fabric,” Gould said, turning the dirt with the toe of his boot.

That’s when Bommarito looked up at the ceiling and uttered a truism about the vintage denim hunt: Sometimes rabies carriers and old blue jeans inhabit the same space.

“There might be some stuff up there next to that nest,” he said. “But I’m not gonna fight the rats for it.”

John M. Glionna, a former Los Angeles Times staff writer, may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com.