‘Taxi wars’ of ’60s predate today’s stand-off with Uber

They’ve been called anticompetitive, protectionist, unfair and un-American.

But the state’s lawmakers had good reason in 1969 to adopt the regulations the taxicab industry abides by today in Nevada.

In the words of former Sen. Richard Bryan, a Democrat who served side by side with Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., in the Nevada Assembly at that time, “all hell had broken loose in the taxi industry.”

Taxi regulations are overseen by the Nevada Taxicab Authority, which was established in 1969 after more than a decade of confrontations among cabdrivers that casino executives feared were getting so violent that they would discourage tourists from coming to Las Vegas.

Now, the regulatory system is again under scrutiny as companies that use technology to match people who need rides with drivers who have cars but aren’t licensed as taxi drivers try to crack the market.

The company trying to gain a foothold in Nevada is Uber, a San Francisco-based outfit operating in 46 countries and more than 120 North American cities. The company views the state’s regulatory system as archaic.

Uber launched operations in October, but suspended service late Wednesday after Washoe County District Court Judge Scott Freeman issued a preliminary injunction preventing the company from operating statewide.

Bryan and longtime industry leaders remember when the legislation was enacted.

“It was ugly,” said Bryan, who in 1969 was a freshman assemblyman from District 4. “There was violence. There were burning cabs. Because of the absence of a regulated structure, there was chaos in the taxicab industry. Finally, there was some strong support from the tourism industry because of its concern as to the impact this had on the visitors’ perception of Las Vegas.”

Jonathan Schwartz, a director for Yellow Checker Star, the second largest taxi company group in Southern Nevada, viewed the turmoil growing up as the son of a Las Vegas taxi company executive.

“The Taxicab Authority was formed as a result of a tumultuous time in the taxi industry known as the ‘taxi wars,’ ” Schwartz said in a recent interview.

“Taxis were essentially unregulated prior to that period and the environment was characterized by fighting among drivers for fares, poorly maintained vehicles, lack of insurance, lack of background checks and a host of other issues,” he said. “Due to the problematic service, the casino industry, in part, demanded that the taxi industry be regulated. The TA is now the foundation of the most stringent set of regulations in the U.S. taxi industry, which accepts nothing short of operational excellence.”

‘WARS’ PUT UNION AGAINST NONUNION

Many of the “taxi wars” battles were waged between union drivers represented by the Teamsters Local 881 and nonunion drivers for companies such as Checker Cab — Schwartz’s father’s company.

One of the first violent acts in the Checker-Teamsters dust-up occurred on Jan. 2, 1969, when a Checker driver was cut in the face when a jack handle was thrown through a cab windshield. Two Teamsters drivers from Whittlesea Blue Cab were arrested by Clark County sheriff deputies and charged with assault with a deadly weapon.

Before the incident, union representatives complained that Checker cabs were blocking the driveway to McCarran International Airport. Checker countered that Teamsters were getting out of their cabs and intimidating passengers into union cabs even though Checker cabs were ahead of them in the taxi line.

Lawmakers had had enough.

Gov. Paul Laxalt backed efforts to regulate the industry. And, when a bill was introduced in the state Senate, he made a strong statement of support.

“This industry has been a legal football for years,” Laxalt said then. “We can no longer afford to play Russian roulette with this problem.”

State Sen. Floyd Lamb, D-Las Vegas, introduced a bill creating a Clark County Taxicab Commission to regulate the industry locally.

Several Northern Nevada legislators opposed Laxalt’s proposal, saying it penalized the whole state for a problem that existed only in Las Vegas. What eventually emerged was an agency overseen by the state that applied only to populations the size of Clark County.

Over the years, statutes were modified and the five-member Nevada Taxicab Authority remains in place and only regulates taxis in Clark County. Cabs that operate in other counties are administered by the Nevada Transportation Authority, which also regulates buses, limousines, towing and moving van companies.

That’s why both the Taxicab Authority and the Transportation Authority are involved in Uber’s bid to operate in the state. The company’s operation in Southern Nevada concerns the Taxicab Authority while its efforts in Washoe County and Carson City is on the Transportation Authority’s radar.

Also, if Uber introduces its Uber Black, SUV and Lux services — the top-tier versions of the company using high-end sedans and sport utility vehicles — in Las Vegas as expected next year, the Transportation Authority would have an interest if they compete with limousines.

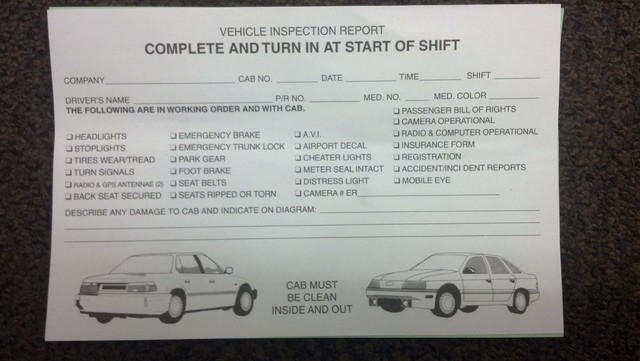

In Taxicab Authority proceedings, licensed operators and driver unions serve as interveners, meaning they are entitled to file legal briefs and provide testimony to the authority board when deciding on issues such as taxicab medallion allocations, rate cases and special medallion allocations for large conventions and special events.

TOP OBJECTIVE: SERVING RIDING PUBLIC

The authority board’s top objective is to best serve the riding public. But state statutes have other criteria that the public has been quick to criticize as anticompetitive and protectionist.

For a new company to operate, the authority board must consider this section of the state statutes, under Nevada Revised Statutes 706.391:

“The granting of the certificate or modification will not unreasonably and adversely affect other carriers operating in the territory for which the certificate or modification is sought.”

That’s why Uber representatives believe getting the “certificate of public convenience and necessity” necessary to legally operate is a long shot. They expect the cab companies to line up as interveners to shoot down any proposal they deliver.

And they’re probably right.

Just ask Jay Nady, who owns A Cab, a small taxi company limited by geographically restricted medallions that prevent his company from picking up passengers east of Interstate 15. Nady has been trying since 2003 to amend his operating certificate to allow him to pick up passengers on the Strip or at McCarran when his West Las Vegas customers request to be dropped off east of the boundary.

He’s argued that he wastes fuel and employee time for his drivers to deadhead back to his zone after dropping off a customer.

Nady’s rivals used all kinds of legal maneuvers to block his bid, and it wasn’t until earlier this month that he finally negotiated a settlement with them to allow about 15 percent of his fleet to pick up east of I-15.

Uber also would have to contend with statutes that require taxi customers to pay based on a meter in the cab. Since Uber relies on contract drivers who use their own vehicles, there’s no taxi meter.

Uber also doesn’t pay the licensing fees that pay for all the regulation the state has mandated.

Schwartz is quick to point out that the state’s regulatory system is built around passenger safety — and companies such as Uber are no match to the safety protocols companies such as his have built over the years. Schwartz can’t even bring himself to call them “ride-sharing companies,” preferring to refer to them as “transportation network companies” or TNCs.

“Without regulation and constant oversight by the Taxicab Authority that the TNCs reject, service to Las Vegas’ tourists would decline dramatically,” Schwartz said. “Uber will attempt to obtain a carve-out set of rules for itself from the Nevada Legislature, which is truly just an expense-reduction ploy that will erode Nevada’s public safety-focused model.”

Schwartz said there’s nothing “sharing” associated with the Uber model.

“They are a transportation company, plain and simple,” he said. “They’re charging a fare. They’re transporting people from place to place. They completely meet the definition of a common carrier under the law. ‘Ride-sharing’ must have been something that some bright advertising or PR person came up with.”

EMPLOYEES VS. INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS

Another big difference between Clark County cab companies and Uber is how they view their own workers.

“There’s a critical difference between having employees and having independent contractors,” he said. “It’s the difference of me as an employer saying, ‘I’m going to be responsible for what you do,’ versus ‘I’m going to disavow responsibility for what you do.’

“The critical difference in the way we view our business model focused on public safety is that we believe one can’t manage a relationship with drivers for the safety of the public without a daily interpersonal relationship whereas my opinion is that Uber believes it can manage that relationship completely over the Internet,” he said. “You can’t do that. It’s reckless. …You’ve got to see them, you’ve got to assess them, you’ve got to look them in the eye every day.”

Schwartz’s company uses technology every day to keep drivers on their toes.

One tool Yellow Checker Star uses is DriveCam, a camera system that captures video images of what’s happening on the road in front of a cab and a separate camera that simultaneously shows what’s going on inside the vehicle.

The camera runs constantly and saves images 30 seconds before a triggering incident — a sudden braking, a sudden acceleration or change of direction, a collision or even hitting a speed bump too fast.

Because the video captures the action leading up the incident, monitors can analyze the footage and coach the driver on how to prevent an occurrence in the future.

Yellow Checker Star runs DriveCam footage on a continuous loop in the driver break room to serve as a constant reminder of things that can happen on the road.

The company also was the first to install a driver training simulator. The three-screen unit, which the company began using in May, lets trainers throw any kind of scenario at a driver before ever going on the road.

New drivers are required to take simulator rides before driving with customers.

Schwartz said safety isn’t the only thing Yellow Checker Star and other Clark County cab companies are addressing with technology. He said several companies are developing a smartphone app that will operate just like Uber’s.

He said testing on the app should be completed by early next year — right around the time lawmakers will be convening and deliberating on what, if anything, needs to be done with the state’s ground transportation regulations.

Contact reporter Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow @RickVelotta on Twitter.