Assemblyman, longtime educator Munford honored for legacy

Overcome by tears as he towered over a microphone in Las Vegas City Hall’s chambers, Harvey Munford touched his chest, spread his arms and leaned forward to sob into his hand.

“Oh, my God,” the 82-year-old retired Nevada legislator exclaimed at one point.

The tender moment occurred moments before the City Council voted unanimously in October to rename Sunny Place, the road he’s lived on for decades, after him.

The new Harvey Munford Street, tucked in a Historic Westside neighborhood, was just one in a long list of accomplishments for a Nevada fixture, who grew up when racial segregation and free-flowing epithets abounded to work through the post-civil rights era into a lengthy career as an educator and six-term state assemblyman.

Munford was the first Black student to attend and to graduate from Montana State University, Billings, where he was inducted into the Hall of Fame as an All-American, two-sport athlete.

He then played professional sports before moving to Las Vegas, where he taught in the Clark County School District for decades and served in the Nevada Assembly from 2004 to 2016. He was known for championing diversity, prison reform and workforce development before he left office because of term limits.

“My father has been a great example to myself and to the community,” his teary-eyed son, Stephen, told the council. “I just want to thank him for giving me a legacy of his last name to carry on.”

At a November street unveiling, the younger Munford again grew emotional as he honored his father in front of dozens who attended the ceremony. He told the crowd about the times Harvey Munford’s rental applications in Las Vegas were denied because of his skin color, decisions reversed only when others with lighter skin tones advocated for him.

Yet, his father never wavered and taught him grace, “even though sometimes the community didn’t love him back.”

Several of Munford’s former students, now middle-age adults, attended the event.

Others wrote online about an educator who helped shape their lives.

“This man was my teacher and friend, and he should’ve been president of the United States,” said one message Stephen Munford read from a Facebook post. “Cause he would’ve changed this world for a better place.”

‘I love Las Vegas’

Munford shares a ranch-style home near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Washington Avenue with his wife, Vivian, 73, and a horse named Majesty.

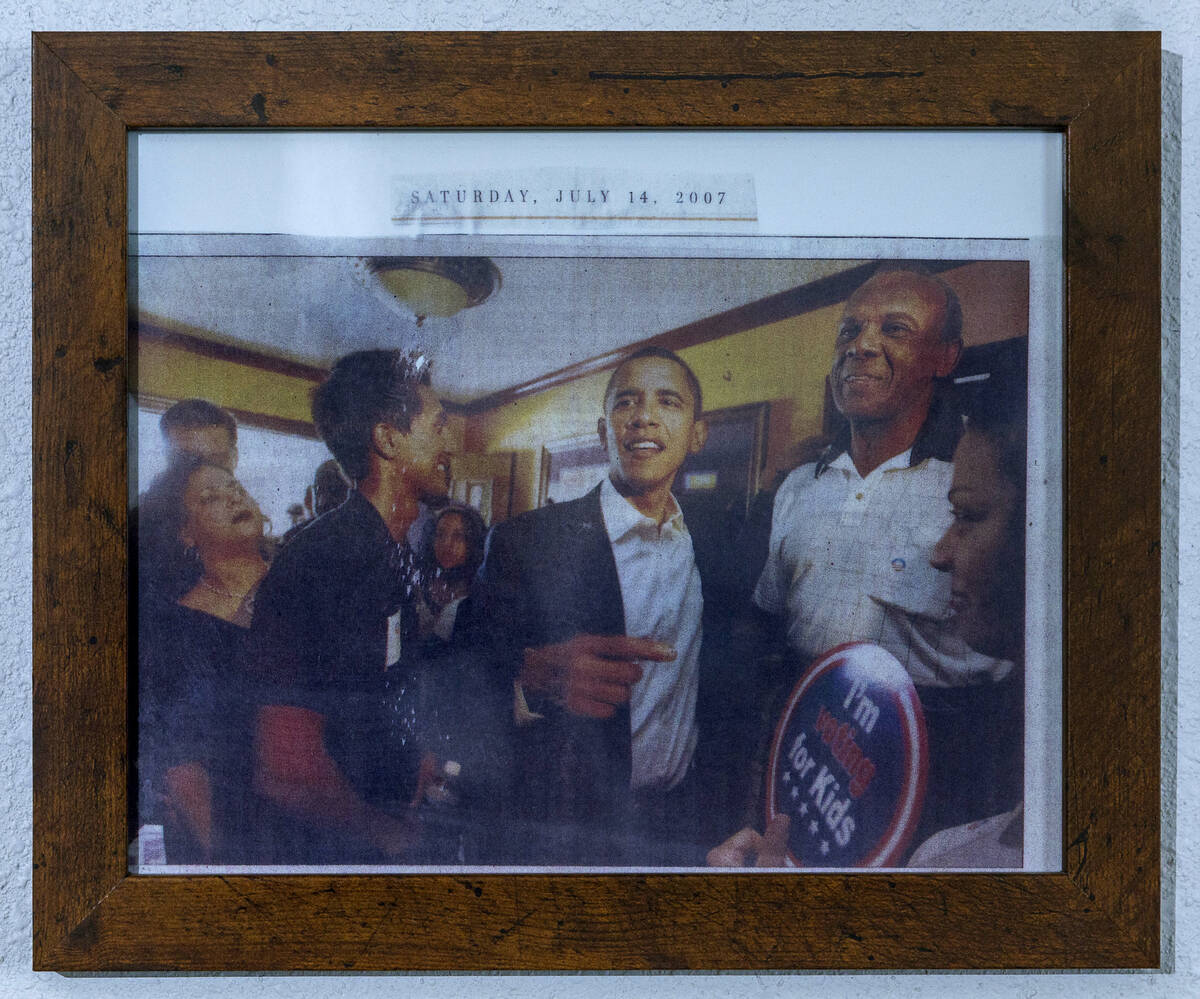

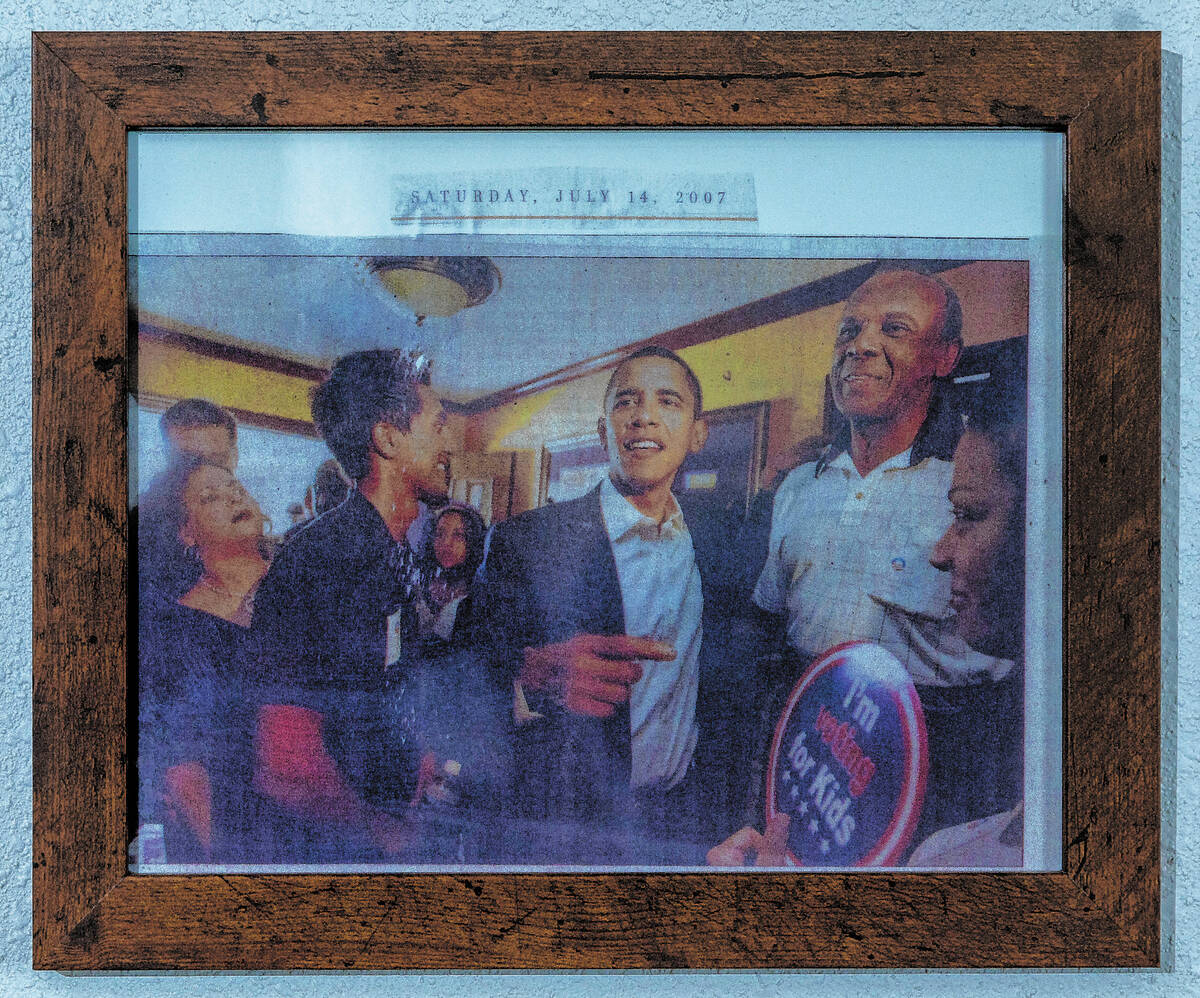

The couple married in the early 1990s and through the years hosted dignitaries at their house for meet-and-greets, including the likes of former Vice President Al Gore and former President Barack Obama, whose photos adorn a spacious meeting space. Other mementos, such as a Raiders-theme shovel the team gifted Munford, were on display.

From that room, Munford shared his life’s story days before the street name was formally changed.

“It was emotional,” said Munford, who stands 6-feet-8-inches tall. “I saw so many colleagues.”

Born in Ohio to church-going parents — a factory worker father, and a stay-at-home mother — who raised four children, Munford recognized his athletic prowess at a young age, but also became keenly aware of the racial division in the evolving country and the cruelty perpetrated against the Black community.

He notes being the same age as Emmett Till when the Mississippi teenager was lynched in 1955.

“I went to a white school in Akron, Ohio,” he said. “But we lived in the Black community.”

He remembered the “N-word” often hurled at him and recalled the inhumanity of not being allowed to share a dance with, let alone date, white girls.

Still, he said, he was voted prom king in high school, the first Black student to hold the honor there.

After grade school, he briefly enrolled at the University of Akron, where he played basketball.

“My ambition was to be a mortician,” he said, but he hung around with the wrong crowd and “didn’t study too hard and flunked out.”

Training to be an athlete

Looking to improve his life, he began running, training with weights attached to his ankles. He still keeps the worn-out weights at home, with a pair of antiquated, ripped-up skates.

The effort paid off, and Montana State’s coach recruited him. He joined the football team his last year and was known to be the fastest player for both teams. In 2013, he returned to the school to give a keynote address for the graduating class.

A few years later, he was inducted into the Montana Football Hall of Fame. He told a news outlet there from the ceremony hall that while he experienced racism at the university, he also encountered kindness.

He met his first wife in Montana, and they share children. She is a county commissioner in that state, Stephen Munford said.

After making history by becoming the first Black student to graduate that university — with a major in biology and a minor in physical education — the Los Angeles Lakers and the NFL’s Rams recruited him. He played pro football for a year during a time of racial riots in Southern California.

He decided to teach when his football career ended. And when he found out the Clark County School District was recruiting Black educators, he and his wife moved here in the late 1960s.

They bought the Sunny Place house a few years later.

Teaching and coaching

Munford taught and coached at K-12 schools and colleges, with his longest tenures at Bonanza High School and the College of Southern Nevada. He also taught at UNLV for about a decade.

“I enjoyed teaching because I wanted to shape and, you know, mold the young people,” he said. Money was not his motivator, he said, noting that his yearly salary early on was about $5,000.

Munford’s current wife met him at a driving school he owned in the early 1990s. His son said that he held four jobs at once at one point.

The Filipino woman had just divorced and was finishing nursing school. Learning to drive was one of her first steps into becoming an independent woman.

“He’s a nice teacher,” Vivian Munford said in a recent interview. “He’s a very, very good person.”

It was love at first sight when he got into the car.

“Immediately when I saw him, my heart pumped so bad, really really hard, and I said, ‘Why is it that my heart beats with this man,’” Vivian Munford told the Review-Journal.

“That means you’re in love,” she said a friend later told her.

They dated a couple years. When she graduated from medical school and her children moved to Las Vegas, he welcomed them into his home.

He wasn’t one to verbally profess “I love you, she said, he showed it with actions.

Vivian Munford described him as an exceptional stepfather who helped raise and put her kids through college.

“He is a good man,” she said.

She offered her full support when he decided to run for office, becoming a campaign worker of sorts. Politics did not change him a bit, she said.

“Now when I say, ‘Harvey, I love you,’” she said, “he will tell me, ‘I love you, too.’”

Asked if he had any regrets, Munford stood over a roll of schematics for a skating rink he had advocated for, but wasn’t built in the Historic Westside. He also mentioned not being able to do more to revive the historic Moulin Rouge hotel-casino.

“When I first came to Las Vegas, the Historic Westside was very productive and it was like Wall Street,” he said. “And that’s why I love Las Vegas,” he said. “That’s why I stayed in Las Vegas.”

Legacy cemented

Las Vegas Councilman Cedric Crear, who introduced the street name change at the council, said the idea was born out of conversations he had with Clark County Commissioner William McCurdy III. Fellow council members, some of whom held back tears, showered him with praise at the council meeting.

At the renaming ceremony, Crear told attendees he first learned about “Mr. Munford” when he was a child growing up in the neighborhood. The councilman highlighted Munford’s yearly Halloween block parties, with the turkey giveaways during the Thanksgiving Day holiday.

“Mr. Munford is a great guy,” Crear later told the Review-Journal, noting that he regularly hears about Munford’s impact in Las Vegas.

“Not just people in the Black community,” Crear said. “That comes from folks that are all over the city. So that’s great; that just reinforces our decision to do what we did, and it really validates it.”

Munford smiled widely at the Nov. 10 renaming ceremony.

After a three count, and eager anticipation from the jovial attendees, Munford pulled a tarp that unveiled a new, shiny, green sign: “Harvey Munford Street.”

He rolled up a fist, and momentarily cried onto it. He quickly regained his composure and flashed a smile as he waved at an adoring crowd that rushed to embrace him and take photos.

Contact Ricardo Torres-Cortez at rtorres@reviewjournal.com. Follow him on Twitter @rickytwrites.