Veterans say legitimate claims routinely denied or ignored

Vietnam War Navy Cross recipient Steve Lowery isn’t alone in his battle to convince the Veterans Benefits Administration that his wounds are linked to his military service.

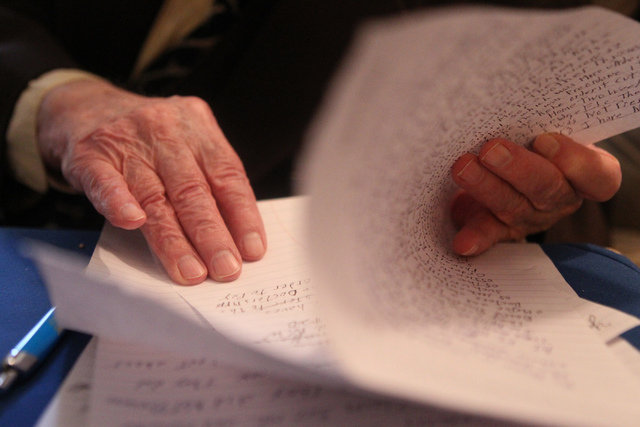

Lowery, a retired Marine major from Las Vegas, took a long-awaited physical examination Thursday at the North Las Vegas VA Medical Center to show a doctor that scars from shrapnel in his knee and those on his thighs from an AK-47 resulted from a 1969 firefight in Vietnam.

In 1994, the VA benefits office in Reno told him those wounds weren’t related to his military service, and he’s been fighting with the agency ever since.

The VA apparently disallowed his initial claim because the government’s archive agency failed to send his records to Reno. Bewildered by the decision, Lowery provided a copy of his personal medical file in 2010. Two years later, his claim was rejected again.

Since the Review-Journal wrote about Lowery’s case last week, other veterans have come forward with complaints about tactics employed by the agency, which demands that veterans prove their injuries were service-related but can deny claims without proving anything.

They include Phil Cushman, a Vietnam War Marine veteran from Oregon who beat the VA system there by winning a “due process” challenge in a federal appeals court that netted $400,000 in compensation. Now, through his nationally recognized nonprofit veterans rights advocacy group, Cushman is helping disabled Korean War soldier Charles P. Mahoney, of Las Vegas, with his appeal for more compensation.

“I’m not filing claims for the money. I want justice,” Mahoney, 82, told the newspaper. “What the VA did to me 60 years ago is they tore up the Bill of Rights.”

Mahoney, who served with the 1st Cavalry Division in Korea in 1950, suffered wounds and mental problems from a mortar blast that heaved him 15 feet into the air. After a hospital stint in Japan, he was taken to Fort Hood, Texas, where he underwent a series of electroshock treatments in 1951 that “blotted out my memory for nine months.”

Two Army evaluation boards determined he was 100 percent disabled, but a third said he was only 10 percent disabled. The Army then told him he was cured and discharged him in 1952.

The VA immediately opened a claim but never processed it or issued a decision and never told him about it. Concealment of the claim effectively denied his right to counsel, Cushman said.

It wasn’t until 2012, three years after Mahoney filed a claim with the VA, that he obtained records showing he had been diagnosed in the early 1950s with a permanent mental disability.

“I thought I was normal, but I wasn’t normal. I had problems with, I guess they call it post-traumatic stress disorder now,” Mahoney said, describing dreams that would cause him to “wake up in the middle of the night screaming.”

“I knew something was wrong with me, but I didn’t find that out until I read (about) my physical evaluation boards that I got out of (military archives in) St. Louis in 2012.”

In resolving his 2009 claim, the VA awarded him 30 percent disability for one year and 10 percent disability retroactive to 1952, a total of about $37,000. But in a 2013 letter to former VA General Counsel Will Gunn that Cushman crafted for Mahoney, the Korean War veteran argued that his rights were violated because the VA and the Army knew his file held two different discharge papers, one of which omitted his mental condition.

This year Mahoney sent a certified letter to the VA Reno benefits office about his quest for 100 percent retroactive compensation to the 1950s. If successful, that could mean Mahoney would stand to collect between $800,000 and $1 million.

The VA signed for the letter but never responded.

Cushman said there are similarities between Mahoney’s and Lowery’s cases — bureaucratic foot-dragging, missing documents, lack of communication and unwarranted denials without regard to the VA’s own doctrine that says the veteran should be given the benefit of the doubt when records are missing or unavailable.

Cushman said the VA’s actions amount to a violation of a veteran’s constitutional guarantee of due process.

“The VA routinely, and as a matter of illegal policy, frequently denies clearly meritorious claims by simply ignoring the evidence and applicable VA laws and regulations,” Cushman said.

Like Lowery and Cushman, other vets and their loved ones have expressed outrage at the way the VA Reno benefits office has handled their claims.

The widow of one Vietnam veteran said the VA constantly dragged its feet in processing her husband’s claim. Many issues related to his bout with illness attributed to Agent Orange exposure, treatment for PTSD, Parkinson’s disease and deteriorating eyesight were in limbo when he died a month after his 63rd birthday.

“Lowery is not a story but a reality of how the Department of Veterans Affairs … (has) failed and still fails to enforce the constitutional rights of our soldiers of wars,” said Johnnette Fafard. Her husband, former Army Sgt. Raymond Fafard, died in 2013.

More than a year after his death, the VA continued to mail him a summary of payments for medical service it made on his behalf.

“Please contact the VA facility listed below ... if you have any questions about the information on this notice or you believe that VA payment was made in error,” reads a Sept. 13, 2014, letter from a local VA office. “Thank you for your military service.”

Johnnette Fafard believes “this is evidence of CUE (clear unmistakable error) done by the VA.

“The VA sent a summary of payment letter to the deceased veteran of 18 months. Why? Was the VA expecting a response?” she asked.

Retired Navy equipment operator Pete Wallace of Pahrump said in a letter last week that he was informed by “A. Bittler” — the same veterans service center manager in Reno who denied Lowery’s claim and handled Fafard’s case — that the VA had no record of him being at Fort Hunter Liggett, Calif., where he was injured in 2000.

Reached Friday, Wallace said he finds that hard to believe because he submitted copies of his orders, a letter of commendation and his medical records “three or four times.”

“I went through the same thing (as Lowery) a few years ago, although for a much lesser injury, and the common denominator is A. Bittler,” Wallace said.

Lowery is now getting some attention from the VA, which scheduled his Thursday medical exam in the wake of last week’s Review-Journal article.

“The Reno Regional Office has worked directly with Mr. Lowery and the VA Medical Center to expeditiously complete examinations so his claim can be processed as soon as possible,” Nathanial Miller, a management analyst for the Reno office, said in an email to the Review-Journal.

But VA Reno officials declined to answer any questions about any of the veteran’s complaints, nor would they even confirm that A. Bittler works there.

A call to Alan L. Bittler in Reno seeking comment for this article wasn’t returned.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.

LOWERY’S STORY

Read about Steve Lowery’s battle with the VA system.