Did someone hire a faux advocacy group to protest the Mayweather-Pacquiao megafight?

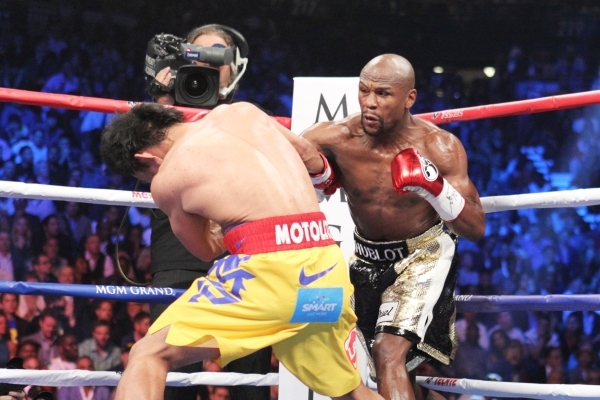

As hype mounted and the money poured in for Floyd Mayweather Jr.'s so-called "Fight of the Century" in Las Vegas, a national conversation began about the undefeated boxer's behavior outside the ring.

Several national news articles questioned why Mayweather, who has done jail time for domestic violence, is able to keep his career unscathed. His bout against Manny Pacquiao was the most lucrative boxing match of all time.

Just before Mayweather would best Pacquiao in the May 2 fight, Deadspin, a sports news website, turned its cross hairs on Las Vegas itself.

The headline read, "This Is How Las Vegas Protects Floyd Mayweather."

The story chronicled difficulties getting public records from Mayweather's court cases and described Las Vegas as a city built to cover up for someone with enough cash.

"His biggest-ever fight is pouring dollars into the city ravaged by foreclosures just a few years ago. Few have any interest in turning off the tap ... What's special about Las Vegas is the openness with which it happens, as if this is just how business is done," Deadspin wrote.

But on the eve of the big fight, some in Las Vegas did seem to care. A group called Hold Athletes Accountable announced a protest to spotlight Mayweather's history of domestic violence, and about 40 people identified as members of the group picketed the prefight weigh-in at the MGM Grand.

But not all was as it seemed. What looked like a grass-roots gathering of concerned citizens was, for some, more like a job. Some of the pickets interviewed by reporters turned out to be public relations operatives, and the protest group appears to have been created mainly to dog just Mayweather.

Who created the group, and why they did it, remain mysteries. Mayweather declined comment for this article.

Secretive protesters

The Hold Athletes Accountable protest prompted some local groups to issue statements against Mayweather, but only one woman from any of those groups appeared at the event: Melissa Clary, vice president of the Southern Nevada chapter of the National Organization for Women, who said at the time that she was not familiar with Hold Athletes Accountable.

Many of the protesters who gathered in front of the MGM Grand that hot day in May had traveled from Los Angeles, but a few identified themselves as locals. Several told the Review-Journal they were not allowed to say how they had heard about the event. Some declined to say anything at all. One protester handed a reporter an ID card but snatched it back when she started writing down his name.

One advocate, Jose Trujillo of Los Angeles, spoke to the Las Vegas Sun and KSNV, Channel 3.

The Sun reported that Trujillo saw many domestic violence victims while volunteering with a crisis response team, which "led him to make the four-hour drive from Los Angeles to Las Vegas to participate."

The day after the fight, though, on his Facebook he advocated a different sort of awareness:

"Grabbing a pair of boobs decreases stress up to 70 percent — Retweet for awareness," read the message he shared. His post featured a photo of a woman grabbing another woman's breasts.

Trujillo could not be reached for additional comment.

Among the protesters was Harris Harrigan, who called himself a Miami-based "grass-roots organizer."

Asked how long he had been with Hold Athletes Accountable, Harrigan said he couldn't remember. He also couldn't say how long the group had been around, who started it, or why.

Harrigan also neglected to mention that he and fellow protester David Abrams ran Abrams Harrigan Consulting, a Miami public relations company whose website, since taken down, listed staging protests among its services.

On the day of the protest, Danny Barefoot, the press contact for the event, told the Review-Journal he didn't think the protesters were paid to be there as he hadn't given Harrigan a budget for that. He later could not be reached for comment. Messages left at the Google Voice phone number of Abrams Harrigan Consulting have not been returned.

This isn't the first time an Abrams-and-Harrigan-affiliated protest has come under scrutiny for paid performances. In May 2013, the two helped organize a protest against Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim. Demonstrators showed up at a Slim speaking event and began laughing at him. According to Forbes, the protesters said they were denouncing Slim's "monopolistic and predatory practices."

Reporters who tried to interview the protesters at that event had trouble getting answers about the organizers. On social media, Abrams took credit for the event, linking to a video of the protest and writing: "Harris and I officially know what it takes to make a video go viral."

Holding boxer accountable?

Hold Athletes Accountable came to life on the Internet just before the fight. Although its stated purpose is "to shed light on the off-the-field, out-of-the-ring records of athletes who commit acts of domestic violence," the group focuses on Mayweather, with only occasional social media posts about other athletes. Protesting Mayweather's fight appears to be its only public event.

The Review-Journal tried to reach Hold Athletes Accountable through social media, by sending messages through the group's website contact portal and by emailing email accounts associated with the group over the course of seven months. In November, the group's Twitter account finally spat back an answer:

"First Regina has a question for you," the tweet read. It was accompanied by video clip from the movie "Mean Girls," featuring a character named Regina saying, "Why are you obsessed with me?"

No other response was forthcoming.

Attempts to untangle the mystery of Mayweather's critics then lead to Sean Holihan of Anvil Strategies, the Washington, D.C.-based political consulting firm responsible for news releases announcing the protest.

Holihan said in November his company slogan — "Helping the Good Guys Do Better" — was involved with Holding Athletes Accountable only for a few months, and he couldn't comment on a former client. When asked if he could get the group's permission to talk, Holihan passed the reporter on to Barefoot, his Anvil Strategies colleague.

In May, Barefoot was the soul of sensitivity, telling Channel 3, "We believe that glorifying and rewarding these known domestic abusers with exorbitant paychecks and public adoration just furthers the cycle of abuse."

Barefoot's response to a request for help reaching Holding Athletes Accountable was significantly less sensitive.

"You'd like some help? For free I'm guessing? We bill by hour here. Would you like our rates? If not, is there a project I can assign you in return? I have a couple of things I could use some help on, normally I would find it inappropriate to email a professional, who I have no existing relationship with and ask for free help, but if we're opening that door … " he wrote in an email.

"We are a business,'' Barefoot advised. "I'm not sure pestering a former client who seems to not want to talk to you is profitable or a good use of my time."

Unknown motives

Thus the mystery of the Mayweather protesters remains unsolved.

There are many reasons why people try and hide that they've backed a movement, said Nancy Weaver, a member of the Public Relations Society of America's ethics and professional standards board. One of the most common motivations is to create the perception of a grass-roots effort, she said. Something that appears to be a spontaneous gathering of different community voices speaking together is seen as more trustworthy, authentic and powerful, she said.

Corporations have a successful history of partnering with advocacy groups, but those relationships work well when their ties are disclosed, Weaver said.

The Public Relations Society of America's ethics code states that transparency, truth and trust are key, said Weaver, who also teaches at the Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

"Unfortunately there are a lot of people out there who hang the public relations shingle in front of their door," Weaver said, pointing out that public relations is not a licensed profession.

"This sounds like a group that maybe has worthy intent to highlight an issue, but it does beg a question when they won't disclose who's funding the organization," Weaver said. "Grass-roots campaigns are successful because of their authenticity. When you're not transparent about who that sponsor is, you undermine the very value of that grass-roots campaign."

Contact Bethany Barnes at bbarnes@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Find her on Twitter: @betsbarnes.