Group works to turn feral cat colonies into ‘retirement communities’

If Clark County’s free-roaming cats could talk, they might compare Keith Williams’ charity work to an alien abduction.

The signs are all there: Strange white vans swooping in, fellow felines disappearing overnight, returning days later with clipped ears and fuzzy memories of operating rooms.

But the well-bearded Williams and his group of 54 volunteers aren’t taking these ownerless cats with malicious intent.

Since 2009 the Community Cat Coalition of Clark County (C5) has been rounding up the county’s estimated 200,000 free-roaming cats for sterilization and vaccination against rabies.

That’s right, 200,000 cats. Roughly the same size as Salt Lake City’s human population.

As Williams, C5’s director, sees it: “Love them or hate them, there’s too many of them.”

The cats blanket Clark County, living in matriarchal colonies that are, on average, 11 members large. Williams said C5’s goal is to humanely turn these breeding colonies into “retirement communities” to reduce the overall population and aggression between males.

“With no kittens, the primary occupation seems to be hitting the food dish and taking naps,” he said.

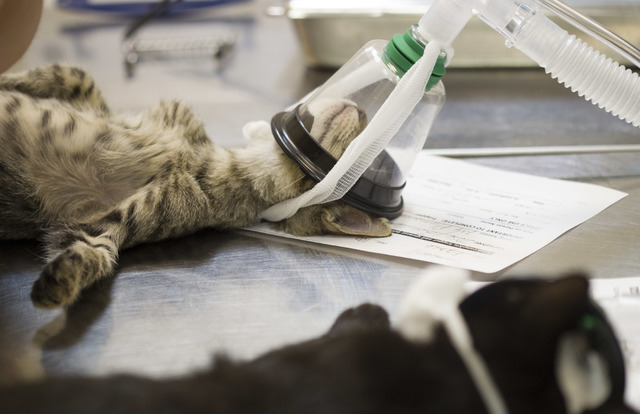

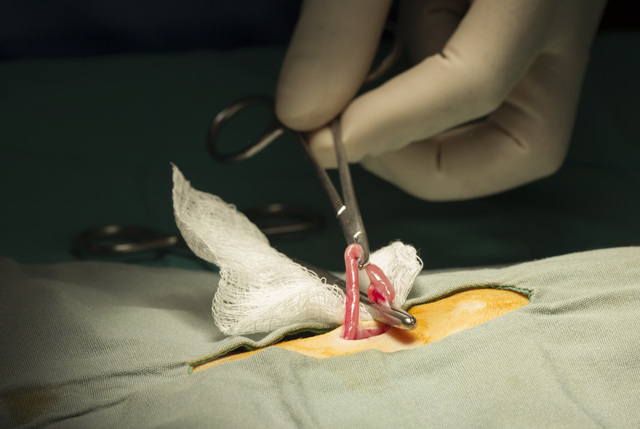

Trap-neuter-return works just like it sounds: Volunteers will trap an entire colony of free-roaming cats, bring them to a local shelter, where they’re treated for about $30 a head, and then return the felines after a few days’ recovery.

Only the youngest cats are kept for adoption. Only the unhealthiest are euthanized.

C5 is fueled by donations and grants from Clark County. One of their vans, a 1997 Ram with wood paneling used to transport cages and cats, is a retired fire department vehicle. They split the cost of treatment with the Heaven Can Wait Animal Society, which runs a local spay-and-neuter clinic.

The nonprofit hit a remarkable milestone, 25,000 cats sterilized, at the end of May. Hundreds of more animals are treated each month.

“That’s over 2,000 locations that are not producing any more kittens,” Williams said. “It goes directly to the source of the problem rather than trying to clean up the mess after it’s already happened.”

As a result, he said, admission and euthanasia rates at the Lied Animal Shelter are down some 75 percent since he and others founded C5 in 2009. That’s a decrease of more than 15,000 cats a year.

Clark County has also undertaken a trap-neuter-return approach.

Chief of animal control and code enforcement Jason Allswang said the combined efforts of local government and nonprofits, like C5 and the Las Vegas Valley Humane Society, are “making a big difference.”

We’re not seeing other cats or colonies moving in and slowly we’re seeing the numbers drop,” he said.

Managing the county’s population of free-roaming cats may seem overwhelming, but for Williams, a retired defense contractor and data analyst with a cat allergy, it’s just a numbers game.

“It’s a very technical problem that needs sorting out, and dealing with technical problems was what I did for a living,” he said.

THE FERAL LIFE

The life of a free-roaming cat in Clark County isn’t one of luxury, according to Williams.

There’s no guarantee of food or shelter. Infectious diseases and predators, like coyotes, can claim a life.

Ninety percent of newborn kittens don’t survive a year.

Adult females become underweight after birthing one to three litters each year. Adult males are shunned from colonies and duke it out over territory and the chance to reproduce.

“We’ll see a 3-year-old cat that looks like it’s just been run through a meat grinder because it’s just fought and fought and fought,” Williams said.

The cats wind up on the streets in a number of ways.

Some are born feral; others are lost pets. Still others, like the friendly “foreclosure cats” that Williams started seeing after the bottom fell out of the housing market, are abandoned by their owners.

The colonies stake out territory, and, if they’re lucky, nearby home and business owners will welcome the furry residents and start setting out food.

C5 usually gets a call a few months after that.

Such was the case last week when Williams and a handful of other volunteers drove to Lucille Thompson’s home.

About a year ago the self-described “bleeding heart” 91-year-old began feeding a trio of felines roaming her neighborhood. By the time C5’s old white van parked in the dirt lot beside Thompson’s home, more than a dozen pairs of tiny eyes were watching from underneath a weathered RV in her driveway.

“I’m so glad you’re here!” Thompson said, clapping her hands as the volunteers placed food-filled traps. “I just couldn’t bear euthanizing them.”

The youngest, most inexperienced kittens entered the long metal cages first, victims of their own curiosity. They inched toward food, before stepping on a panel that shut the cage door behind them.

It was a familiar sight for volunteer Joe Hamrock, a 46-year-old computer engineer who has been trapping cats for the last 15 years.

“Hunger is the key,” he said. “If you get out here and they’re not hungry they’ll just sit around.”