Las Vegas cop behind controversial killing now influential union leader

Detective Bryan Yant was the face of incompetence at the Metropolitan Police Department: a poster child for wrongful shooting deaths and million-dollar payouts, a driving force behind sweeping reforms to the agency’s deadly force policies.

In other cities, an officer who kills an unarmed man under suspicious circumstances and is accused of lying to cover his tracks might be prosecuted. In Las Vegas, Yant kept his job.

And he’s taken on a role that will make him more influential at Metro.

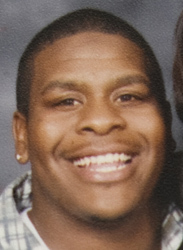

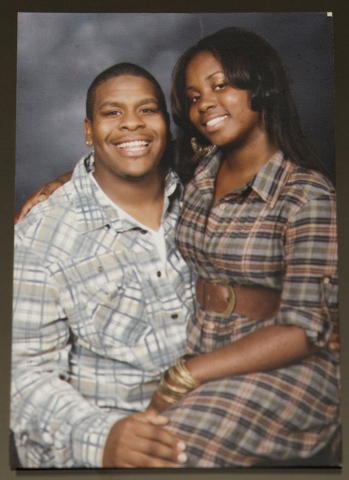

The officer, infamous for the 2010 killing of Trevon Cole, a small-time marijuana dealer, is doling out advice in his new job as a union director in the Las Vegas Police Protective Association.

Part of Yant’s duties include advising officers in police shootings, said Chris Collins, executive director of the union that represents rank-and-file Metro officers.

“He’s a huge asset to the union,” Collins said. “Bryan Yant lived through the hell of being in a police shooting.”

Yant, a 14-year veteran, has been in the position a few months and has already responded to “a few” police shootings, although Collins declined to say which ones.

“When he goes out in these situations he can tell somebody that it’s like biting a s—t sandwich. You’re not going to like it, but you’ll get through it,” Collins said.

Yant has more experience with police shootings than just about everyone at Metro. Most police officers never fire their weapons, but Yant shot three people — killing two men and wounding a third — in his first 10 years on the job.

He shot and killed Richard Travis Brown after a foot pursuit in 2001. Two years later, he shot and wounded Melvin Gilchrist after mistaking a baseball bat for a gun. Both shootings had significant problems, with Yant’s version of the events failing to match either evidence at the scene or witness testimony.

But neither of his earlier shootings were as controversial as the night raid into Cole’s apartment on Bonanza Road on June 11, 2010.

Yant, while working with an undercover narcotics unit, targeted the 21-year-old after he bought 1.8 ounces of marijuana from Cole in four exchanges over several weeks.

But Yant made mistakes during his investigation, confusing Cole with someone with the same name who had a lengthy criminal record in other states. That person did not match Cole’s description or age, but a judge approved a search warrant with the false information.

Yant also made significant mistakes during the raid.

After he kicked in the door to Cole’s pitch-black apartment, he rushed to the bathroom to find Cole flushing marijuana down a toilet.

Yant said Cole, who was unarmed, lunged at the officer as if he had a gun. Yant shot Cole once in the head with his AR-15 rifle, which had a flashlight that wasn’t working.

But the evidence, as in his earlier shootings, didn’t match his story.

During a Clark County coroner’s inquest two months after the shooting, Assistant District Attorney Chris Owens noted that the position of Cole’s body and the downward angle of the bullet through his cheek to his neck pointed toward an accidental discharge.

“That version is consistent. Your version is not. How do you explain that?” Owens said.

Yant was unable to explain the discrepancy.

“I’m not a forensic scientist,” he said. “I’m not a physicist. I don’t know. That’s what I saw.”

Yant stuck to his story, and the coroner’s inquest jury — an often-criticized rubber-stamp process that has since ended — ruled the shooting justified.

Owens wasn’t the only one who thought Yant wasn’t telling the truth. Owens’ boss, then-Clark County District Attorney David Roger, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal he thought Yant lied on the stand. But there wasn’t enough evidence for criminal charges to be filed.

“We still believe that it was an accidental discharge,” Roger said after the inquest, “but we have to respect the jury’s verdict.”

Roger quit his job as district attorney a year after the inquest and joined the police union as general counsel. Roger did not respond to questions this past week about his union’s decision to appoint an officer he’d publicly accused of lying.

The Cole killing was one of three major shootings in 2010 and 2011 that prompted Metro, with the help of the U.S. Justice Department, to overhaul its deadly force policies, including its internal use-of-force disciplinary board. Many officers believed Yant would have been fired if the harsher policies had been instituted at the time.

Yant was one of several problem officers identified in “Deadly Force,” the Review-Journal’s 2011 series on police shootings.

Cole’s family later received a $1.7 million settlement from Metro, the highest single payment for a police shooting in the department’s history.

The family’s lawyer, Andre Lagomarsino, said he was surprised and disappointed about Yant’s new job.

“I’m no public relations expert, but probably not the best move if you’re the PPA,” he said. “(Cole’s) family would be extremely upset to hear about this.”

Reaction to the move within Metro has been mixed. Several officers told the Review-Journal that Collins and the union likely took Yant to irk outgoing Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie, who had promised to keep Yant in desk jobs for the rest of the officer’s career.

That was better than firing Yant, Gillespie said, because there was a chance Yant could appeal his firing. If he won in arbitration, Gillespie would have no choice but to reinstate Yant to his former position as a detective. By choosing to suspend Yant instead, Gillespie could control his place in the department, he told the newspaper.

But the union has a lot of leeway when it comes to choosing its board members, and that’s one way to free an officer from the sheriff’s grasp, officers said.

“It’s a big f—k you to the sheriff,” said one veteran officer who asked not to be identified.

Gillespie said he didn’t look at it that way. He could have raised an issue with Collins, but his chief concern was ensuring Yant didn’t have any assignment involving contact with suspects, he said.

As for Yant’s credibility in his new position? That’s a question for the union, the sheriff said.

“There was a number of people who questioned Bryan’s testimony in regard to what occurred that evening,” Gillespie said. “But he stuck to his original statements, and he was the only one right there at that time (of the shooting).”

Collins acknowledged that the union approached Yant for the cushy, competitive gig but denied that the move was to incite Gillespie. Yant had been working at Metro’s fusion center — apparently helping write Metro’s new body camera policies — at the headquarters of the Southern Nevada Joint Terrorism Task Force, Collins said.

He defended Yant’s actions in the Cole shooting and said he had no qualms with the officer representing the union.

“The bottom line is if you open the door when police knock, when they have a search warrant, you don’t get shot,” he said. “(Cole’s) actions played a huge part in him being shot.”

Other officers were embarrassed that Yant was representing their union, however, and questioned what advice he’d give to officers in shootings.

“What is he going to tell them?” one officer said. “To lie?”

Contact reporter Mike Blasky at mblasky@reviewjournal.com. Follow @blasky on Twitter.

DEADLY FORCE

Read the Review-Journal’s award-winning series on police use of deadly force.