Police academy recruits endure harsh road

They stand on the sidewalk in two lines, staring straight ahead in silence.

The Las Vegas dawn washes the nearby rocky foothills in a stunning orange glow, but the 23 men and four women in matching black running shorts and light blue T-shirts don't seem to notice.

For them, this is more than a new day. This is a new life.

They come from all walks of life -- among them a 21-year-old security guard, a 37-year-old track coach, a 30-year-old mechanic and a 41-year-old Air Force veteran -- but none of that matters on this June morning.

Today they are all simply police recruits, each hoping to have the will, skill, discipline and desire to survive the next six months and earn the badge of a Las Vegas police officer.

When the clock strikes 6:15, they get the first taste of what lies ahead at the Metropolitan Police Department Academy.

"Quit freaking looking around!" officer Dean Leslie barks as he emerges from the academy gate.

Four other officers follow him into the frenzy, yelling in ears, shouting in faces:

Adjust your hands!

Yes, sir!

Is that all you got?

Yes, sir!

Louder!

Yes, sir!

"If you're going to sound off, you'd better sound like you want to be here," Leslie growls.

The recruits scamper inside, hauling their wheeled duffel bag, shoulder duffel bag and garment bag with them.

Hurry up!

They've barely assembled in a large, lecture-hall-style classroom when Leslie barks new orders. Change into their tan recruit uniforms. Three minutes.

The men and women split up, scrambling to their respective locker rooms. In the men's locker room, a couple of officers wade through the flurry of flailing arms and legs, cranking up the stress as the half-naked recruits frantically change.

"You're not going to make it ladies," officer Jonathan Simon bellows over the chaos.

Simon spots a recruit, shoes in hand, heading for the door in his white socks. But he is supposed to be in black socks. Simon stops him and screams. The terrified recruit scampers toward the door, slipping on the linoleum in his white-socked feet on his way out.

Simon eyes another recruit's black polished shoes. He runs his finger across a heel and closely inspects his smudged finger with disgust.

"This is not Kiwi. That's fake shoe polish," he screams as the recruit scrambles from the locker room.

Time's up, and the remaining recruits race to the classroom, still stuffing belts into pant loops and shoving shoes on to feet. The recruits stand at attention behind their assigned seats as Leslie frowns beneath his graying crew cut.

"Freaking wake-up call!" he shouts, his voice filling the room. "It ain't no joke. When I tell you to move, you're gonna freaking move!"

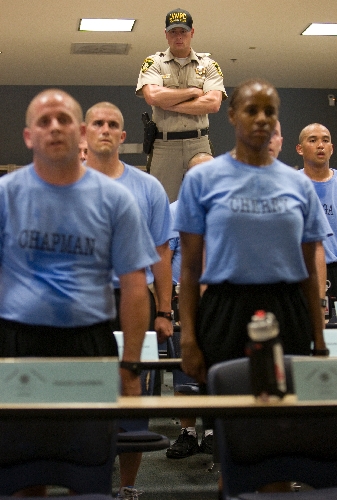

With the recruits standing in various states of disarray, a handful of officers circles them like a pack of wolves stalking prey. They lurk on the fringes of the room, scanning for a sign of weakness -- an unbuttoned shirt pocket, an unnecessary twitch, a wandering eye -- then pounce on the fresh meat.

Like wide-eyed deer on the plains, the recruits have nowhere to hide. Each one is in survival mode, terrified of the next attack, hoping the next bite goes to a classmate and not them.

"Claaaaaasss, take seats!" Leslie barks.

The recruits settle into their plastic swivel chairs.

"Back up. Too frickin' slow!"

The process repeats several times as the recruits learn how to sit at the academy. Spin the chair. Slide in. Hands on knees. Stare straight. Don't move. All as one.

They bumble through, and Leslie is furious.

"Show some pride, people. This is a career, not a freakin' job. If you want a job, go back to where you freaking came from," he says.

For most of them, the classroom is a long way from where they came.

Months ago they were mechanics, business owners, security guards, military men, retail clerks and even a staffer for a congressman. Some dreamed of being cops their entire lives. Others, academy staffers suspect, joined for the good paycheck in a down economy.

They started by filling out applications and taking a test alongside a couple thousand other police hopefuls. They passed written and physical fitness examinations. They passed drug tests and background checks. They passed psychological exams.

Each step whittled the numbers a little more until 26 men and four women were hired to fill Class 6-09, the sixth academy class of 2009.

Three of them would be gone by the start of Day One, and another 10 would quit by graduation day.

This is what happened in between.

A week before Class 6-09 began, relatives and loved ones of the recruits gathered in the same classroom for Family Night, where academy staffers explain what's in store for them.

"If they haven't prepared for this, they're in for a rude awakening," says Sgt. Dan Zehnder, who oversees the Training and Counseling officers. One TAC officer is assigned to each class to serve as a mentor, coach and disciplinarian.

Anyone can make it through the academy, but it's not easy, he said.

Much like military drill instructors, the academy staffers will break the recruits down, then build them up. If they don't have the commitment for the job, they won't make it to graduation, he said.

They will learn under a revised academy curriculum and structure that Zehnder calls "Cop 101." The program was overhauled in November 2007 when the department was in the middle of hiring 600 new officers under the More Cops sales tax initiative of 2004.

Previously, the department ran three or four police academies a year, each with 100 to 120 recruits. Because of their size, the classes were heavy on lectures.

Under the new program, that number was slashed to 45 recruits. Class 6-09, the last class fully funded by More Cops money, began with 30. The smaller classes made it easier for recruits to learn and harder for them to hide their shortcomings.

The revamped curriculum focused on the basic tasks of a patrol officer. No more learning about blood spatter patterns and other advanced topics no beat cop in Las Vegas has to worry about.

Classes were more hands-on, with fewer lectures and more practical learning scenarios.

Under the revamped program, more recruits quit during the academy, but more make it through field training, a five-month on-the-street training regimen that teams new officers with veterans.

Under the old program, 19 percent of recruits dropped out of the academy, and 17 percent didn't finish field training. Under the new system, the academy attrition rate spiked to 31 percent, while all but 8 percent of the new officers made it through field training.

As he wrapped up his talk with the recruits' loved ones, Zehnder told them they would be the keys to the recruits' success. Not only would they need to keep them focused and help them study, but they would have to assume more household responsibilities such as paying bills and taking out the trash.

Between long days at the academy and long hours of homework, the recruits won't have time. For the next six months, they'll eat and breathe the police academy.

"Your life goes on hold," Zehnder says. "That life has to be put away."

Nathan Herlean was an Air Force brat who moved 15 times before his family came to Las Vegas when he was a senior in high school.

He always wanted to be a police officer, but life took him in other directions first.

After high school, he attended Brigham Young University, then completed a two-year Mormon mission in the Dominican Republic. When he got home, he married Brittany after a three-month courtship and joined her father in the real estate business.

He went to night school at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, got his degree in business management. He sold hundreds of homes in Las Vegas, and he thought he had a career for life, he said.

Yet the thought of being a police officer lingered. Herlean recorded every episode of "COPS" he could find. He joked with his wife about becoming a cop. He made the Metropolitan Police Department's recruiting site his web browser's home page. He even filled out the online application a couple of times but didn't send it.

Then the real estate market collapsed. The 29-year-old was working nights and weekends to make ends meet for his family, which had grown to include three sons.

After talking about becoming a cop for two years, he finally sent in the application.

Six months later, he was standing on the sidewalk with 26 others in the pre-dawn twilight, getting chewed out by a bunch of intimidating, tough-looking cops. He hoped to become one.

"I was scared to death of these guys," Herlean says months later. "I just kept telling myself, 'Don't worry, it's going to get better. ... It's just this game.' But it felt like it never ended."

After a morning filled with stress and screaming, Zehnder allows the recruits to relax, for a few hours anyway, while he talks to them about the academy and the history of policing.

Zehnder, an All-America distance runner in college, served 21 years in the Army, including stints with Special Forces, airborne and armored corps. He came to the Metropolitan Police Department at 38, older than all but three of the recruits sitting before him.

"Clearly, many of you are not prepared this morning," he says in the gravelly voice of the grizzled general in a Hollywood blockbuster.

They've entered what Zehnder calls the toughest all-around police academy in the country. Some might be more physically challenging, some more academically challenging, but none will tax both the mind and body like this one.

He reminds the recruits that they aren't in the civilian world anymore. Shifting blame and making excuses won't cut it here. Everyone is accountable for everyone else.

Cops are held to a higher standard, so when one screws up, they all screw up. Everyone pays.

And he reminds them that being a police officer carries risks that few jobs do, so they shouldn't stick around just for the paycheck.

"In 95 days, you're going to be on the streets of Las Vegas," he says. "There are no dress rehearsals. You could lose your life on your first day on the job."

On the projection screen behind Zehnder, the photos of every agency police officer killed in the line of duty appear, including those from the Las Vegas Police Department and Clark County sheriff's office, which merged in 1973 to form the Metropolitan Police Department.

The last photo is officer James Manor, who died a month earlier in a crash while speeding to a call.

Manor was in the last large academy class before the revamp, he says.

"That's what we're here for. No more of this. No more," he says earnestly, motioning to Manor's photo. "Your journey starts now."

Day One has almost ended for Class 6-09, but not before the recruits get another taste of stress.

Zehnder gives them 30 seconds to stow all of their gear in their bags. They rush from their seats to the back of the room, each one charging to be first, or, at least, not last.

They don't make it. They get another 30 seconds. Then another 15 seconds.

The fast recruits rush back to their seats and stand at attention panting for breath, seemingly pleased with their success, while fellow recruits struggle to finish on time. They're acting like individuals instead of a team, and Zehnder is not happy.

He sends them to change into their workout uniforms. Three minutes. Go.

The recruits rush out the doors. When time runs out, nine recruits don't make it.

Everyone drops to the floor and does 10 pushups, followed by squats and arm circles.

They're still acting as individuals, Zehnder tells them.

"We expect that to happen, but not for much longer," he says.

They run in place. More push-ups.

Change uniforms again. Some don't make it, again.

Sit-ups. More pushups. More running in place.

Sean Barrett, a tall, lumbering man whose paunch curls over his waistband, labors through the exercises. He signed up at 41 after 22 years in the Air Force.

"Just quit, Barrett," says Leslie, himself a former airman. "Those 22 years don't mean anything here, Barrett. You're going to be treated like everyone else."

The recruits get 90 seconds to get their garment and duffel bags from the locker room. They fail.

"No sense of motivation," Zehnder says. "You're already starting to piss me off. Don't worry, every class pisses me off. You're only thinking about the easy way. That's why you can't get this done in the allotted time."

The recruits rifle through their bags and get another 20 pushups for each missing piece of equipment or clothing they were required to bring.

Barrett scrambles to find space for pushups on the crowded classroom floor.

"Any day Barrett. You're always freaking last," Leslie growls.

Four minutes to put their gear back in their lockers. They shove their clothes and gear in their bags and scramble up the aisles toward the door.

They don't make it.

More pushups. More sit-ups. More running in place.

Someone left shoes out. Another 100 pushups are added to the running total.

A locker's left unlocked. Another 20.

Two and a half minutes to change uniforms. Too slow. Five-hundred more pushups.

More squats. Scissor kicks. Pushups. Sit-ups

"The trouble with dealing with me instead of your TAC officer is I just don't know when to stop," Zehnder says.

Change uniforms. Three minutes. Go.

The recruits hustle now, running to their spots instead of jogging. They reach their seats, huffing for air. Two recruits straggle in late.

Change uniforms. Three minutes. Go.

"You're going to learn to move with a sense of purpose," Zehnder says.

Three don't make it. Five-hundred more pushups, bringing the total to 2,500. The recruits will do all of them by the end of the academy, 10 pushups at a time.

The recruits run to the field for more pushups. They grunt and groan, pain and exhaustion on their faces.

Barrett, with one sock ripped and frayed, gets pulled from the group and sent to the shade of a nearby wall.

"You're not ready for this," Zehnder tells him.

Barrett's sagging face agrees.

The class runs inside, failing to beat the time limit again.

"You're all thinking as individuals. Where's MY bag? Let me get MY stuff," Zehnder tells them.

With a little bit of teamwork and organization, the class could have easily accomplished the tasks, he says.

"Quit worrying about yourself. Start worrying about the team."

The class assembles in the parking lot for more pushups before rushing out the gates that brought them into this agony. As they run out, Leslie shouts his cell phone number.

"You can check out. I don't care," he says. "All you have to do is call me."

Day One is officially over for Class 6-09, but the recruits are huddled outside before heading home. Some take charge. They assign tasks. They share tips for changing clothes faster. They organize.

They begin to show the teamwork Zehnder was looking for.

Only 95 more days to go.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281.

The Making of a Cop

COMING MONDAY: 'No quitters'