A trip beneath the Nevada State Museum reveals 225M years of Nevada history

Sarah Hulme walked backwards with her hands stretched across time.

“We are now spanning 225 million years as we stand here,” the Nevada State Museum’s outreach coordinator declared, leading two journalists into an aisle in the museum basement. The warehouse-esque storage room was dim and dry; it had to be to preserve the new, old and ancient artifacts and pieces from the state’s history within its walls.

To her left, headdresses worn by showgirls during the now-defunct “Les Folies Bergere” show that lasted nearly 50 years at Tropicana, hanging from a wall upside down to protect their shape.

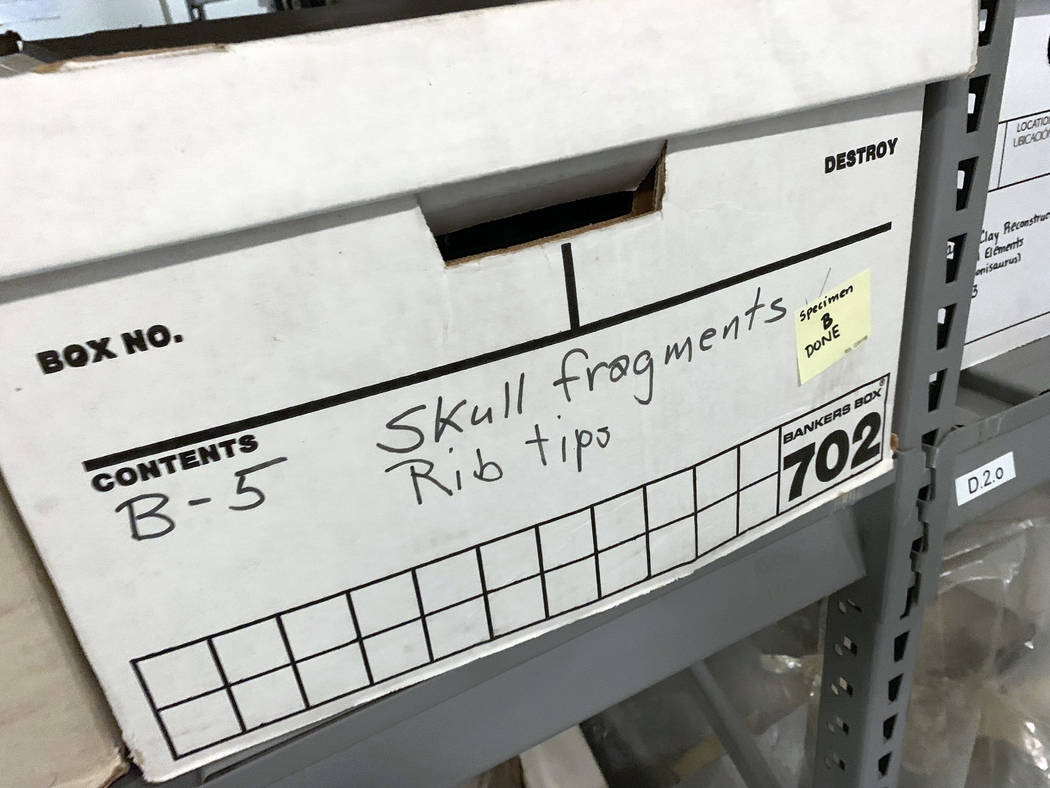

To her right, the fossilized bones of the ichthyosaurs that ventured to the waters of the Great Basin during the Mesozoic Era, packed away in boxes lining the shelves.

“If you were a paleontologist, you would rebuild an ichthyosaur from these boxes,” she said.

The museum maintains the most complete collection of ichthyosaur (Greek for “fish lizard”) fossils in the world and represents a leading reference point among paleontologists on the long-extinct sea creature, Hulme continued.

Ichthyosaurs were found across the planet but mothers came to Nevada to give birth to their young. Elsewhere, they could be the size of a pony, she says. Here, they could resemble a floating bus.

She says this aisle is one of her favorites because it represents all of Nevada’s history: “This is what the museum is.”

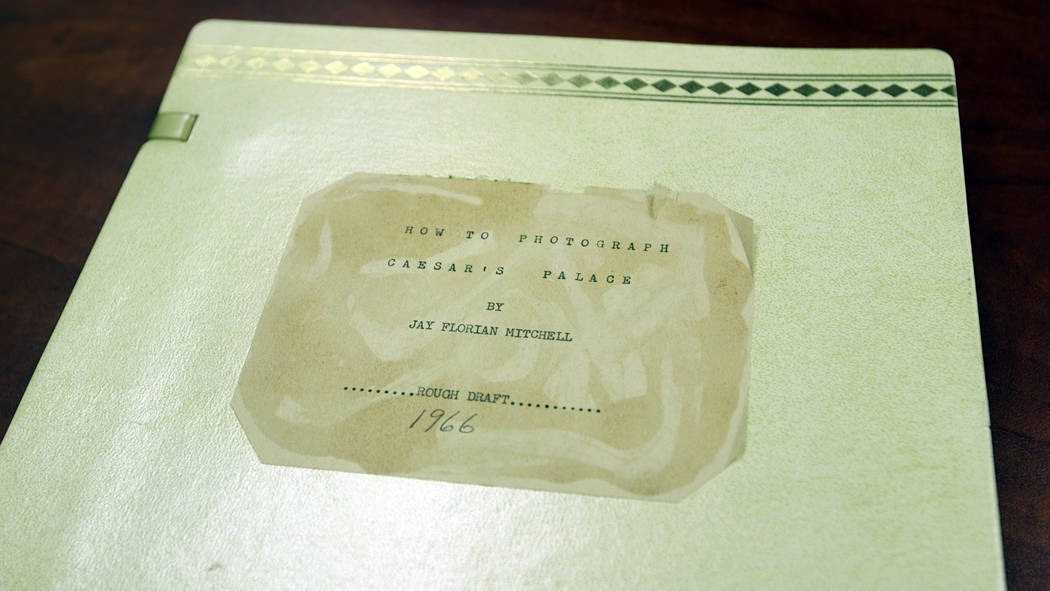

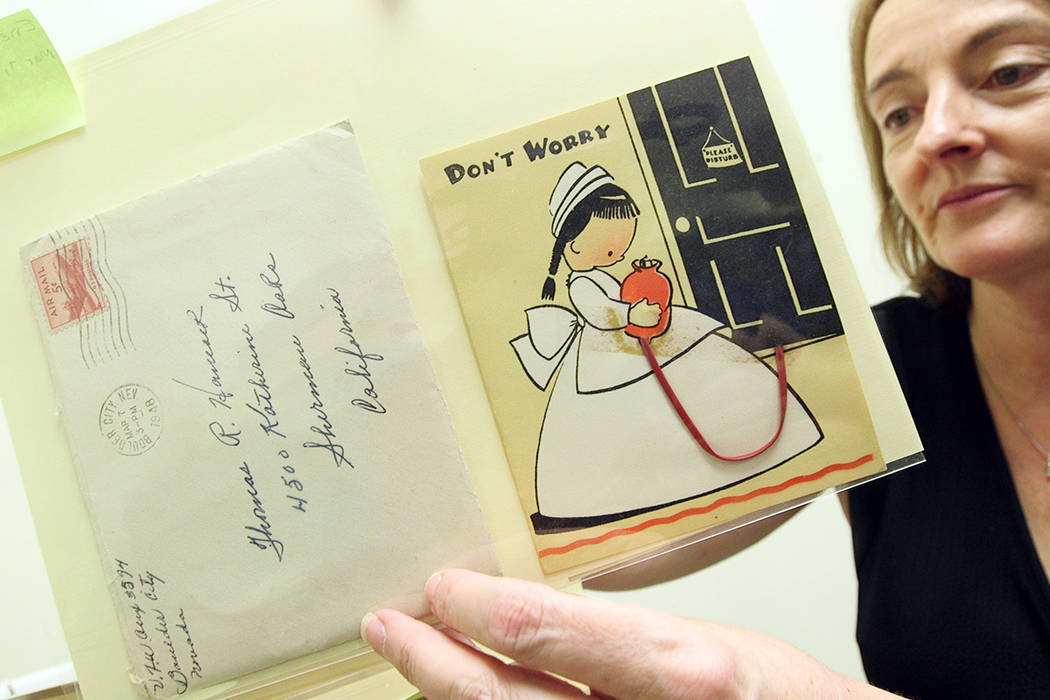

Beneath the museum’s public space hides an incomprehensible accounting of the state’s history. Thousands and thousands of photos, historic footage, artifacts, outfits, trinkets, knickknacks, fossils and memorabilia lie in storage, waiting for the day they are unearthed and displayed in the right exhibit.

Hulme explains that museum staff will plan out temporary exhibits a year or two in advance. It takes that long to formulate the concept, identify what the museum possesses to fit it, determine whether additional pieces are necessary to complete it and execute the design, she says.

There’s no hard and fast rule on what “triggers” an exhibit, Hulme says. A significant artifact, piece or addition to the museum could be cause for a new exhibit. So can a moment in time.

The museum was working to put together an exhibit commemorating the history of sports in Nevada, she said. It was the right time to do so, as Las Vegas hosts the Golden Knights, Aces, Lights and Aviators and will soon claim the Raiders. The exhibit’s opening would coincide with the Raiders’ arrival in 2020, she says.

As part of their efforts, museum staff asked Golden Knights fans to donate their tickets and memorabilia for posterity.

“History doesn’t always have to be the past,” Hulme posits.

Each exhibit is built from the ground up, she said as she led the reporters through the carpentry room and workshop. Once settled on an idea, the museum constructs the mounts, displays and cases, as well as the signs — now in both English and Spanish — for each exhibit, she says. The state-funded museum relies on its roughly 60 to 70 volunteers to research, catalogue inventory and build the exhibits.

Some pieces are reused. A rather lonely man, a long, grayed beard affixed to his waxy face sat in a workshop room chair with one arm posed to hold the other.

“He’s been many thing things over the years,” Hulme says of the dressed mannequin missing a finger. “He may have been (John C.) Fremont in his last guise.”

A door guarding the museum’s items greets intruders with a yellow warning of an extinguishing system: “keep door closed at all times.”

It guarded the cavernous storage spaces holding pieces old and new from a telephone exchange to a cross memorializing the Oct. 1, 2017 massacre. A collection of moths and butterflies 22,000 strong paired with an herbarium consisting of the plants on which they lived, fed and bred highlighted the once-living residents of the museum storage.

Another of those residents arrived (alive) at the museum as a baby - Norbert, a leopard frog tadpole. He lived in the museum’s education room, where kids could watch him grow and metamorphosize over the course of his life. Hulme would post progress updates about him on “Tadpole Tuesdays.”

“This is what he looks like this week — look at his little legs growing,” she recalls. “And then I got the call: ‘Sarah, Norbert has passed.’ I was like, ‘He hasn’t grown to a frog yet!”

Norbert, similar to the animals that typically arrive at the museum already dead, was frozen until the museum acquired the funding to send him out for taxidermy, Hulme says.

On a late-August day, Norbert sat on a table next to two taxidermied songbirds; a black-throated gray warbler and a western meadowlark in a singing pose.

“Norbert will live forever,” Hulme affirms.

Someday her little preserved friend will return to public display. Until then, he’ll remain beneath the feet of museum patrons along with the rest of Nevada’s hidden history, frozen in time.

Contact Mike Shoro at mshoro@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @mike_shoro on Twitter.

Nevada State Museum

Where: 309 S. Valley View Blvd.

Hours: Tues. through Sun., 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (Closed Mondays)

Admission: Free for children and members of the state museum system or Springs Preserve. $9.95 for Nevada resident adults. $19.95 for non-Nevada resident adults

Phone: (702) 486-5205