‘It was so unsafe’: Hospital patients discharged to homeless shelter, unregulated facilities

On a rainy day in January, a bus dropped off brain-injury patient Chester Duhamell in a wheelchair outside a Las Vegas homeless shelter following his discharge from Desert Springs Hospital Medical Center.

The concerned driver called the 59-year-old’s wife in Arizona. The hospital had not notified Vanessa Duhamell that it would discharge her husband that day, she later said.

She called the couple’s daughter in Las Vegas, who was at work and didn’t get the message right away.

It would be several hours before Duhamell’s family would find him — shoeless, coatless, soaked to the skin and smelling of urine.

“They dropped me on the sidewalk, and I was to fend for myself,” Duhamell said in a Zoom interview.

“It was so unsafe,” said Vanessa Duhamell, whose husband remains physically and cognitively impaired from a stroke. “That somebody could actually do that to another human being is unreal.”

Discharged patients who are still recovering from illness or injury are regularly left at the Courtyard Homeless Resource Center, a city of Las Vegas representative said. Frail patients also are discharged to unregulated facilities or sent home in the middle of the night in ride-hailing vehicles without a guardian or caregiver first being notified, records show.

Adding to questions surrounding the case was that Duhamell was not homeless.

Fines by state regulators for discharge violations are rare. The Las Vegas Review-Journal found only two instances in more than five years in which regulators had fined a Las Vegas-area hospital for the manner in which a patient was discharged. The largest fine was $1,500, according to documents obtained through public records requests.

The Duhamells’ daughter, Erin Mcguire, drove the homeless corridor near the resource center of downtown Las Vegas, shouting for her father from her open window. She then parked blocks away and began to search on foot among the throngs of people huddled outdoors in the downpour.

She said she found him outside the center under an awning that partially blocked the rain. A homeless woman, who had given him a pair of socks and a blanket, told Mcguire that if it was her dad, she would have wanted someone to make sure he was OK. Mcguire insisted the woman take the $80 in her wallet.

Desert Springs leads in citations

Since 2018, regulators have cited Southern Nevada’s major acute-care hospitals for discharge planning deficiencies at least 11 times, a review of complaint reports shows.

Nathan Orme, an information officer for the Bureau of Health Care Quality and Compliance, said the state has not seen evidence that unsafe discharges are a growing issue, but that there have been a “quantity of inappropriate discharge complaints over time.”

An improper discharge tends to be an isolated incident, he said, “rather than a facility-wide issue affecting multiple patients.” Yet it is “always a very serious issue to the individual whose care is neglected by such a discharge.”

Of these 11 instances of deficiencies, three pertain to discharges from Desert Springs, the highest number for any hospital. These instances are in addition to the claims by the Duhamells, who did not file a complaint with state regulators.

Desert Springs, located east of the Strip on Flamingo Boulevard, stopped admitting patients in the spring.

Five of the 11 complaints involve hospitals within the Valley Health System, a subsidiary of Universal Health Services, which includes Desert Springs. Prior to Desert Springs’ closure, the Valley Health System operated six, or nearly half, of the area’s 14 major acute-care hospitals.

Under Nevada Administrative Code and federal rules, a hospital is required to identify each patient who is likely to suffer “adverse health consequences” absent adequate discharge planning. A hospital must consider patients’ ability to care for themselves and to make an appropriate placement after discharge.

Recent data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services shows that only 43 percent of Desert Springs patients upon discharge understood what their care would be after they left the hospital, which is below the national average of 51 percent and the state average of 47 percent.

“There are care plans in place so patients and/or family members receive verbal and written education prior to discharge,” Valley Health System representative Gretchen Papez wrote in response to a Review-Journal inquiry.

Anecdotal information suggests that unsafe hospital discharges are a significant problem across the country, but little data is collected on the issue, said Charleen Hsuan, an assistant professor of health policy and administration at Pennsylvania State University.

Federal regulations are comprehensive, said Toby Edelman, a senior policy attorney with the Center for Medicare Advocacy. However, “they’re only good if they’re enforced,” she said, noting that the manner of a patient’s discharge “is not something that gets an enormous amount of attention” from regulators.

Nowhere to go

Because Chester Duhamell had acquired a contagious condition, planning for his discharge became an odyssey, his wife said.

Two years after a stroke left him partially paralyzed on his left side, the heavy machinery mechanic fell and hit his head, which caused bleeding in his brain and required hospitalization. He was discharged to a long-term acute care facility, which later released him to a rehabilitation facility.

Once the rehab facility learned that he’d acquired Candida auris, a serious fungal infection often transmitted in medical settings, it transferred him to Desert Springs in September 2022.

The hospital failed to find an appropriate rehabilitation facility that would accept him while he still tested positive, his wife said, noting that he had insurance.

In addition to needing rehab, being discharged home wasn’t an option. Vanessa Duhamell, who is in end-stage kidney failure, said her nephrologist told her she could not risk becoming infected with the deadly fungus.

Last December, the hospital proposed transferring him to a homeless shelter or weekly motel, his wife said. The family objected, noting he was unable to live by himself.

Papez said she couldn’t comment on an individual patient’s situation because of patient privacy laws.

Hospitals regularly experience discharge bottlenecks because of the limited number of post-acute-care beds, she said.

“Depending upon each patient’s unique circumstances, we work with them, their families, outside health care facilities, agencies, case managers and community health workers for the best possible discharge for all patients,” Papez wrote.

But Vanessa Duhamell said that once her husband no longer tested positive, the hospital quickly released him before making contact with her.

‘A disservice to human beings’

A discharged patient who remains medically fragile is dropped off at least once a week at the homeless resource center, said Kathi Thomas with the city of Las Vegas, which operates the center where people can stay and get a meal, a shower and housing assistance.

“They have come in Ubers or taxis. Or they show up in a hospital gown with their hind parts showing,” said Thomas, director of community services. “We don’t always know the backstory. But it happens frequently enough that we’ve been concerned. … I think it’s a disservice to human beings.”

Hospitals are under pressure to release patients once insurance no longer covers a stay, she said. There also are too few beds in rehab and other facilities to accommodate all the discharged people.

The city operates a recuperative care center near the resource center for those still recovering. Patients must be referred to the facility by a hospital, a shelter or the city’s street medicine team. With just 38 beds, the care center’s size is inadequate to meet the community’s needs, Thomas said.

The homeless and the poor are especially, though not exclusively, susceptible to unsafe hospital discharges.

Hospital regulators cited Valley Hospital Medical Center, another Valley Health System facility, for the manner in which it discharged a homeless woman last November.

Videotape footage showed security guards escorting the woman, who normally used a wheelchair, out of the hospital with only a walker. KSNV-TV, Channel 3 footage showed the woman falling to the ground as the security guards walked her off hospital property.

The state fined Valley Hospital $1,500 in connection with the incident, records show.

Papez said that when a hospital undergoes an investigation for a discharge planning concern, it analyzes its processes to make any necessary adjustments.

Discharging to unregulated facilities

Regulators have cited hospitals for discharging medically fragile patients to unregulated facilities, investigation reports show. The state can notify a hospital of violations without fining them.

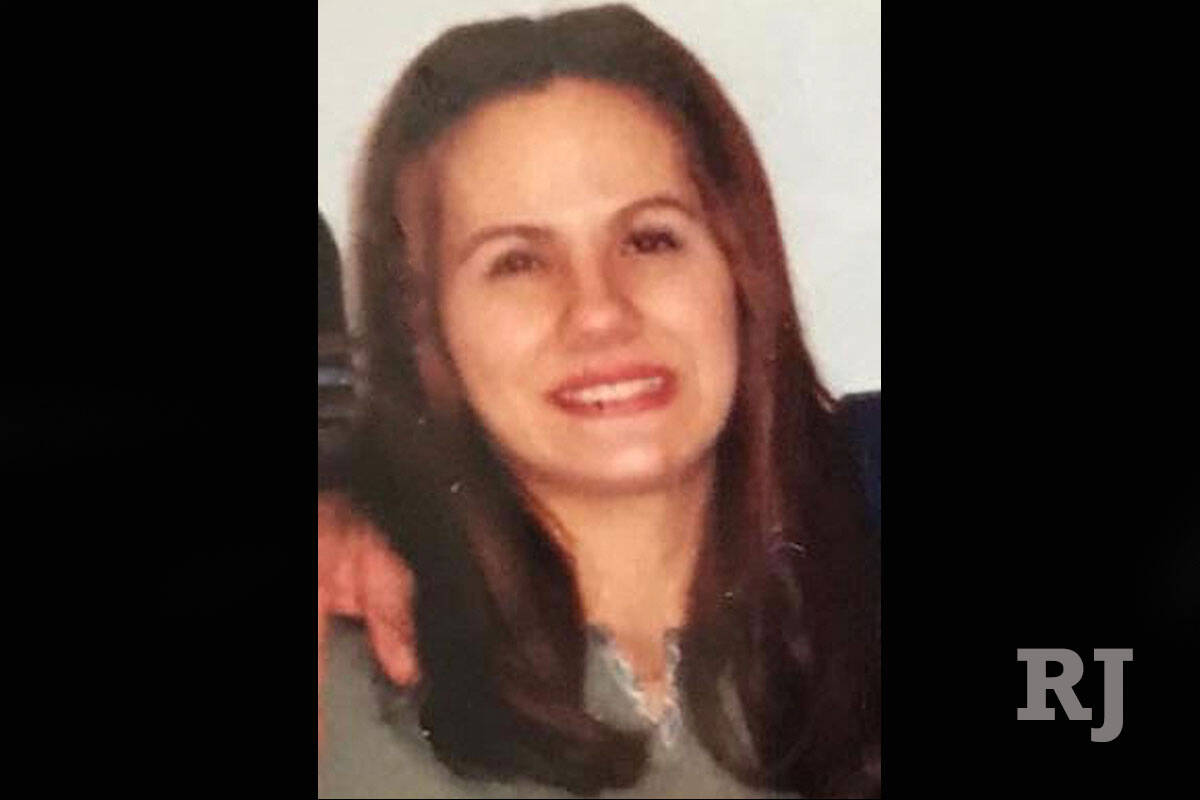

The state cited North Vista Hospital in North Las Vegas for discharge deficiencies after it released a severely mentally ill woman to an unregulated independent living facility. According to a police report, the 48-year-old woman, who had been on suicide watch at the hospital, killed herself the day after her discharge.

A case manager said the patient was discharged to the first independent living facility that would take her and not to a licensed group home, a type of facility that provides a higher level of care, because she “did not have the financial means to pay for a licensed group home,” a citation report states.

During her hospital stay, the nursing staff documented the patient’s ongoing attempts to harm herself.

The patient was Ethel Christian Girard Mateos, her aunt, Josefina Pacheco, told the Review-Journal in 2018.

“They should have kept her there at the hospital or found another place where they could treat her better,” Pacheco said.

Regulators in 2019 fined North Vista $800 for discharge planning deficiencies in connection with the incident.

“Fining is one of the few pieces of hospital discipline that we have,” said David Himmelstein, a distinguished professor of public health at The City University of New York and a lecturer in medicine at Harvard University.

But he said the fines need to be stiffer to change behaviors.

“Eight hundred dollars is nothing to a hospital,” he said. “That’s what they charge for an aspirin tablet.”

In 2018, the state cited but didn’t fine Desert Springs Hospital for discharging a partially blind, diabetic woman to an unlicensed, unregulated group home.

The woman had been discharged two months before a state inspector uncovered her situation. The home’s operator told the inspector that the hospital had paid her to take in the 57-year-old woman, which the hospital disputed, saying it had paid only for rent, records show.

The inspector observed the woman keeping her insulin, which required refrigeration, in a dresser drawer.

Discharges overnight, in ride-hailing vehicle

A failure to notify a patient’s guardian at discharge accounted for three citations, the most frequent type of discharge deficiency.

Discharge planning violations capture only a portion of what could be considered unsafe discharges. Many questionable discharges fall under other categories of deficiency.

For example, regulators cited a hospital under a provision related to providing emergency services when it discharged a developmentally disabled patient late at night without notifying his public guardian. The patient, who was given a bus pass by the hospital, was found after riding the bus all night, records show.

Patients’ families complained about their loved ones being sent home in ride-hailing vehicles. One such incident proved to be tragic, according to a lawsuit filed last December in District Court.

Marceil Scott, 87, came to the ER after a fall, but Centennial Hills Hospital Medical Center released her in the middle of the night, putting her in a ride-hailing vehicle without first contacting her caregiver or son, according to the lawsuit. She was not wearing a coat that freezing night and did not have her walker.

After being dropped off at her house, Scott, who had some mental impairment, could not remember the code to the keypad to enter her home, according to the lawsuit. She fell on her front lawn, where she was not discovered until the next morning. She returned to the hospital with hypothermia and injuries. She died a month later.

Legal counsel for Centennial Hills, a Valley Health System hospital, told the Review-Journal earlier this year that the nursing staff and physicians met the standard of care at all times.

If you’re thinking about suicide, or are worried about a friend or loved one, help is available 24/7 by calling or texting the Lifeline network at 988. Live chat is available at 988lifeline.org.

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MaryHynes1 on X. Hynes is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.