Afghan refugee grateful for escaping Taliban’s threats, terror

Ahmmad Khan, a wiry 56-year-old, possesses something most people his age in Afghanistan don't have: an education.

Schooled at Kabul University, he learned to teach Farsi, the Persian language spoken in Afghanistan and bordering countries. He taught it to children, adults and even teachers. Sometimes he turned the living room of his small home in Kabul into a makeshift classroom.

He lived a relatively quiet life until the mujahedeen -- so-called holy warriors -- started shooting rockets and setting off bombs.

In the early 1990s, several years after the mujahedeen drove the Soviet military out of the rugged, mountainous country, he expanded his communication skills to include writing short stories and documentaries. While working as a teacher-trainer, he helped the Ministry of Education refine some of its publications so that those who could read could grasp the information more easily.

During the 10-year Afghan-Soviet war and its aftermath, Khan steered clear of politics and focused his efforts on keeping his family safe while educating others.

"It was a simple life, just a simple life," he said last week in his daughter's Las Vegas home, while his wife and members of their immediate family listened.

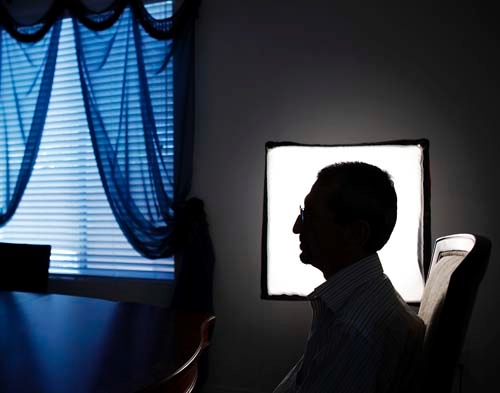

Khan agreed to talk about why he left his native Afghanistan to come to the United States and how he was reunited with his family thanks to the help of Rep. Joe Heck, R-Nev.

He asked that his real name not be used because he feared retaliation against relatives who remain in Afghanistan.

Heck's spokesman, Darren Littell, confirmed that Khan worked as a translator for the U.S. military in Afghanistan. Because of his service, he was eventually granted asylum. Later, Heck's staff arranged for the rest of his family to be reunited with him in the United States.

THREATS AND EXTORTION

Even though the mujahedeen succeeded in preventing a Soviet takeover of Afghanistan, life became miserable for the Khan family. Although there was a government on paper, it had little or no impact on day-to-day life in the capital city.

Life was governed by threats and extortion. Every month, sometimes every week or so, the mujahedeen and later the Taliban -- the equivalent of the Afghan mob -- would knock on the door and demand money. When people didn't give all or most of what was demanded, the gun-toting thugs would rape women and children, or shoot them dead.

They have no regard for life, Khan said.

"The Taliban is the worst people in the world, I think. They don't know anything about Islam, their humanity," he said, adding that they just want to be in control, a spinoff from their training in Pakistan.

As the Taliban grew in power, he lived in constant fear because his wife, four daughters and young son made his family ripe for extortion.

The Taliban never tried to recruit him because he was an educated man, even though his language skills might have been an asset to their cause.

"They cannot go to the educated people. They are going to the uneducated," he said. "When the people are educated, they are not going to fight with each other."

He estimates that the vast majority of Afghans -- 98 percent -- have little or no education from schools in the country.

In fact, the Taliban try to keep the people uneducated, he said. "They come in and blast schools" after they've been constructed in nation-building efforts by U.S.-led NATO troops.

FLEEING TO PAKISTAN

After Osama bin Laden masterminded the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Khan adopted a new role in Kabul as a translator for U.S. forces who were sent to find the al-Qaida leader and destroy Afghanistan's safe harbors for terrorists.

As U.S. forces established outposts throughout the country, life in Kabul became more treacherous for Khan and other Afghans sympathetic to the American presence. In late 2001, his oldest daughter married a U.S. citizen and moved first to Southern California and then to Las Vegas looking for work.

"Life was too hard to live in Afghanistan. Pakistan was more safe," Khan said.

His family found themselves among some 3 million refugees who fled to Pakistan.

"It was an open border," he recalled. "We took a big bus."

Like many, they found safety for a while in Pakistan's capital, Islamabad. There, the problem was not the Taliban but the local police. At night, they would knock at their door and demand money.

In short, they were forced to pay to stay in the country, "sometimes once a month or twice a month," he said.

Occasionally police would stop them at the market.

In 2008, in exchange for his help in Afghanistan as a translator, State Department officials arranged for Khan to come to live with his daughter in Las Vegas and obtain a green card.

Until recently, he worked as a minimum wage employee stocking shelves in a grocery store.

He said one reason he left Islamabad is because "the Taliban is growing up in Pakistan. The second reason is this was not a place to send our daughter and son."

His observation is that Pakistan has a different view of America's presence in the region, especially since U.S. special operation forces succeeded in killing bin Laden during the May 2 raid on his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

"It is not a good life. The Taliban is not thinking about life of humans. They are killing right now, not thinking about man or woman or kids. They are just killing without any reason, without thinking."

'EVERYTHING IS FREEDOM'

In five years, Khan hopes to have achieved his goal of becoming a U.S. citizen.

Here, he said, his young son can ride his bike to get a chicken sandwich at Jack in the Box without fear of a roadside bomb blowing up. And, his wife can shop for groceries without worrying that she will be stopped by the police who ask to see her visa and demand money for being in the country.

"When I go outside for a walk, the kids say, 'Hi. Hello. How are you doing?' There is peace," he said. "There is everything. ... Everything is freedom.

"Unfortunately, in the Third World it is different. They are thinking about themselves. Here they respect elders and respect kids."

He said the biggest misconception Americans have about Afghanistan is that "sometimes they think all Afghans are Taliban. They are not. I'm sure they are not.

"They are good people, they love their country. I want them to become a good country, a good friend for the United States."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.