Gilcrease animals get along fine, but humans keep squabbling

If you're living at the Gilcrease Nature Sanctuary, odds are you survived some sort of trauma.

Bambi, a female mule deer, was so new to the world that she still had the umbilical cord dangling from her belly when somebody dumped her at the front door three years ago.

Green-winged macaws Bonnie and Clyde, the only bonded bird pair to survive a fire that ripped through the sanctuary last year, are separated while Bonnie recovers from a throat infection.

Even William Gilcrease, the reclusive 93-year-old founder, endured povertylike living conditions while the Las Vegas land empire he and his deceased brother, Ted, once oversaw dissolved. Caretakers and managers orchestrated controversial real estate sales worth tens of millions of dollars that never seemed to result in major upgrades to the sanctuary.

Now the sanctuary Gilcrease took a lifetime to cultivate is suffering trauma of its own.

Lawsuits have been filed, accusations have been made, and infighting has erupted between board members and others vying for control of the organization, and as much as $4 million that is thought to be in its coffers.

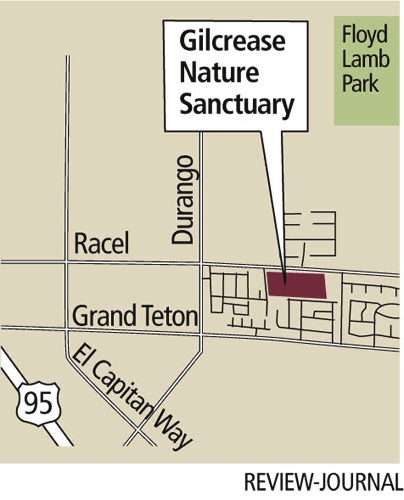

The battles threaten to overshadow efforts to have the approximately 9-acre property at Racel and Al Carrison streets annexed by Las Vegas. That is part of a broader plan to rehabilitate the sanctuary for more than 1,000 native and exotic birds and other animals so it can become a sustainable community attraction after Gilcrease is gone.

"Even with all the hell they've been through, they still could be in a strong position," said historian Joe Thompson, a friend who frequently checks in on Gilcrease. "Personally, you hate to see places like this go down, because there are so very few community places in Las Vegas."

SANCTUARY FROM SUBURBIA

The nature sanctuary isn't much to look at from the entrance off Al Carrison. The parking lot is a narrow strip of asphalt that abuts a shabby, two-story wooden home with a brown plastic-and-wire fence screening the inside from public view.

The rustic look is in stark contrast to surrounding neighborhoods made up of large, modern stucco homes and new shopping centers that characterize the area about 15 miles northwest of downtown Las Vegas.

Past the fence is a small, concrete courtyard bordered on the north by Bambi's roomy pen, which includes a small house with climate control provided by a swamp cooler.

To the east lie several acres of cages, pens and ponds that are home to macaws, cockatoos, parrots, parakeets, ducks, geese, swans, ostriches, emus, goats, miniature horses, donkeys and tortoises, among other creatures.

It took Gilcrease years to build the menagerie, mostly through a willingness to shelter and care for whatever happened to land on his doorstep.

"In the old days if somebody died or they had a drug bust and they had exotics, nobody would take them, so Mr. Gilcrease would take them," Executive Director Barbara Price said during a recent tour. "There was nowhere else for them."

The enclosures are shaded in some cases by sagging rooftops, mature trees and modern, reflective plastic.

In the center is a small amphitheater with a concrete stage and grass-covered seating. A large pond is fed by well water, to which the sanctuary has rights to 40 acre-feet annually.

Over the entire property is a cacophony of birdsong, screeching, honking and huffing.

"We were mostly just a family ranch pieced together until the fire," Price said, referring to the March 19, 2010, electrical fire that ripped through a portion of the sanctuary and killed about 200 birds and Zapato, a pet dog.

Workers have mostly repaired damage from the fire, but the incident is still seared into their minds, Price said.

"It was absolutely horrible and heartbreaking and everything else."

One of the most difficult jobs was breaking and removing slabs of scorched concrete. "It was a constant reminder," Price said.

Despite the makeshift nature of the sanctuary, the animals appear well cared for, the enclosures are clean, cool and shaded, and walkways are passable.

During the tour with Price, Rachel Kamaunu, 37, of Longview, Wash., and her children Emily, 4, and Mason, 1, strolled across the grounds.

The kids pushed their way to the edge of a pen where they could feed several goats that sidled up for handouts.

Kamaunu, who lived in Las Vegas for 13 years before moving away about four years ago, described the sanctuary as an affordable respite from the city.

She said shade from the mature trees makes the preserve pleasant even during hot summer days, and the birds and animals entertain the children.

"I love it. It is great interaction," Kamaunu said. "The kids get to see the animals. You don't get to do that in a lot of places."

Maintaining the property is full-time work for several people.

Price, General Manager Oscar Gilcrease, adopted son of William, and several workers and volunteers are on the grounds daily. They feed and monitor all the birds and animals, clean cages and walkways, and maintain the structures.

Price said cleaning and maintenance is crucial as the sanctuary looks to evolve from a curiosity for neighbors and locals into a higher-profile destination for visitors that attracts corporate and foundation support.

"People with money don't want their name associated with it unless it looks good," Price said.

SANCTUARY'S TURBULENT PAST

While Price and other workers use shovels and brooms to clean the sanctuary, cleaning up legal and financial messes dating back many years isn't so simple.

The Gilcrease Nature Sanctuary was the overlooked affiliate of Gilcrease Orchards, a popular pick-and-pay farm overseen by the late Ted Gilcrease.

Both properties are vestiges of a Gilcrease land empire that peaked in the 1950s at more than 1,500 acres.

According to the organizations' websites, the sanctuary was established in 1970 and the orchard in 1977.

William was a co-founder of the orchard with Ted, who died in 2003.

In recent years the two properties became the subject of scrutiny. This was particularly true around 2005 when longtime manager Mary Ellen Racel sought to sell to Spinnaker Homes 40 acres of orchard property for a reported $15 million to $20 million.

News reports quoted critics who questioned whether the sale was necessary and wondered aloud what happened to millions of dollars in proceeds from earlier land sales.

The publicity also put the spotlight on Racel's relationship with William, whose signature was needed to sign off on transactions.

"I think that she got Mr. Gilcrease to sign papers and she was disposing of different parcels of land to developers," said former Clark County Commissioner Thalia Dondero, now a member of the sanctuary board. "I don't know what her motive was, but somebody made money."

Thompson said William Gilcrease was neglected and lived in poor conditions during Racel's watch, despite his valuable land holdings.

"I found somebody who was incredibly neglected and was just astonished at the conditions he was being kept in," said Thompson, who first visited William in 2003 while gathering material for an oral history project. "He was living in there in absolutely filthy and neglected conditions. He was not eating properly. It was just disgusting."

In an interview, Racel and her partner, Maureen Mackey, said the land sales were necessary to keep the orchard afloat and that William's living conditions were the result of his own eccentricities.

"She made sure he had round-the-clock nurses. He fired them all, of course," Mackey said.

"The bottom line was Bill has always lived the way he had with his animals in the house doing their thing," Racel said. "Bill was the best example of a hoarder I could think of."

Racel was forced out through a lawsuit from William Gilcrease, the Gilcrease Orchard Foundation and the sanctuary.

The lawsuit took two years to resolve and, in addition to ousting Racel, resulted in a $4 million grant from the orchard to the sanctuary.

Despite protestations from Racel, people close to Gilcrease say his health and living conditions improved after the ouster, even though he still doesn't have the trappings associated with most people who have millions of dollars in assets.

"In my mind this guy should be pampered and elevated until the day he dies," Thompson said. "That being said, he is much better off than he was before."

Dondero concurred.

"We talked to him the other day and had a meeting with him. He looked really good," Dondero said, adding that Gilcrease retains his tender touch with small animals and birds on the grounds. "You just never know. Sometimes he has little birds in his pocket."

Attempts to contact Gilcrease directly for an interview were unsuccessful.

Oscar Gilcrease referred a reporter to Diana Foley, an attorney representing his father.

"I don't think he is ready," said Oscar Gilcrease, who works on the sanctuary grounds. "You would have to talk to his lawyer."

Foley said in an email that Gilcrease "does not wish to make a statement at this time."

Although Gilcrease and his sanctuary appear to be in abler hands following the previous lawsuit, it isn't the end of the organization's legal battles.

The current board is embroiled in another lawsuit filed in June by ousted board President Elanor Ahern and current board member Sue Newman.

Ahern was voted onto the board in April and elected board president in May, after lobbying for the positions with promises of financial contributions to the sanctuary, other board members said.

But just 10 days after Ahern was elected president, she was ousted in a vote her lawsuit states violated the organization's bylaws, according to the complaint.

Ahern contends in her lawsuit that other board members and Price resisted her efforts to force an audit of the organization despite evidence of shoddy bookkeeping.

Ahern attorney Michael Root cites a letter from accountant Mark Alden complaining of incomplete and inconsistent records and lack of cooperation within the organization.

"We're unsure of the accounting facts now," Root said. "We just want to find out what the truth is. We hope there is no looting."

Others tell a different story.

Dondero and board member John Foley, who also is the sanctuary attorney, say Ahern was voted out because of a series of strange actions following her election as president.

Almost as soon as Ahern was elected, they said, she had the locks changed on the sanctuary and removed important paperwork from the premises.

"No one has the right to come in and all of a sudden change all the locks," Dondero said. "It is an organization; it isn't anyone's personal operation except Mr. Gilcrease's."

Dondero said the lawsuit is a costly distraction from the pending annexation, which will help the sanctuary link up to the city sewer system, and a renovation of the property.

"I'd rather see the money go to the sanctuary and improvements we need to make and to the birds and animals," she said. "What we are trying to do is make it into a more presentable place."

Ahern and Newman have been seeking to sow doubts about the annexation at city meetings when the subject was on the agenda.

Ahern told council members she was wrongly voted out as board president and questioned whether Gilcrease would have to move off the property if the annexation goes through.

She also said Price wasn't authorized to sign papers on behalf of the sanctuary. So far, city officials appear poised to allow the annexation to go forward.

"He is not going to have to leave the property," Ward 6 Councilman Steve Ross, whose ward includes the sanctuary, told Ahern and Newman after a recent City Council meeting . "I'm not going to do anything that harms Bill Gilcrease."

GRINDING FORWARD

On a sunny day midweek at the sanctuary, there is no evidence of the looming legal clouds.

Price is hustling around the property with engineer Joe Haun, surveyor Mike Holton and two visitors.

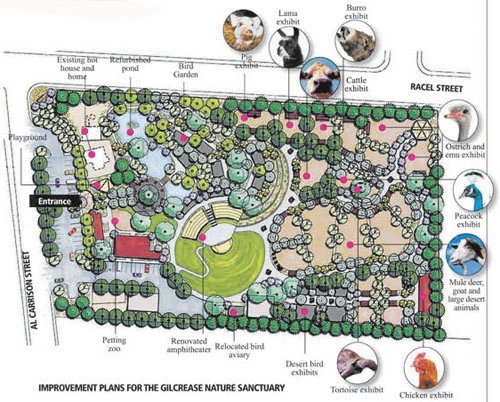

She's carrying a bright green, glossy book that contains the sanctuary master plan.

Haun and Holton say they will be ready after the annexation to plan and design phase one, a remake of the parking lot, facade and entry way.

The entire renovation budget for seven phases that would remake the entire sanctuary is just $500,000 from the $4 million grant, according to Price.

The rest of the money is set aside for investments aimed at spinning off interest income to fund operations.

By starting with the parking and facade, Price and the others hope to attract attention to the sanctuary that could lead to more visitors and contributions.

"One of the reasons they chose to go with the front is to get that curb appeal," Haun said. "Right now you could practically drive past this place and not notice it."

If more money comes in, the remaining phases of the master plan call for updated exhibits and an expansion onto about four acres that are mostly unused.

Backers envision more trees, plants and educational exhibits aimed at teaching people about natural history, culture and the responsibility required to own exotic birds and other pets.

But Price says no matter what happens, the plan is to keep the sanctuary simple and friendly, the way Gilcrease was known to operate the property.

"We're going to keep as much of a rustic, natural feel as possible. We don't want to go all neon, you know," Price said. "We don't even want fake rock, like Springs Preserve. We are going to try to make it as natural as we can."

Contact reporter Benjamin Spillman at bspillman@ reviewjournal.com or 702-229-6435.

Gilcrease Nature Sanctuary and master plan