Hummingbirds filmed taking fast drink in Vegas

As a freelance photographer for more than a half century, Don Carroll has weathered his share of challenges.

He has traveled around the world using special effects to capture unique angles for images for the covers of fashion magazines.

His photo of a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, the Dalai Lama, graced the December 1992 cover of Paris Vogue magazine.

And while living in New York with his wife, Noriko, on Sept. 11, 2001, he grabbed his camera and rushed to the World Trade Center to capture the chaos in the wake of the hijacked jetliner attacks.

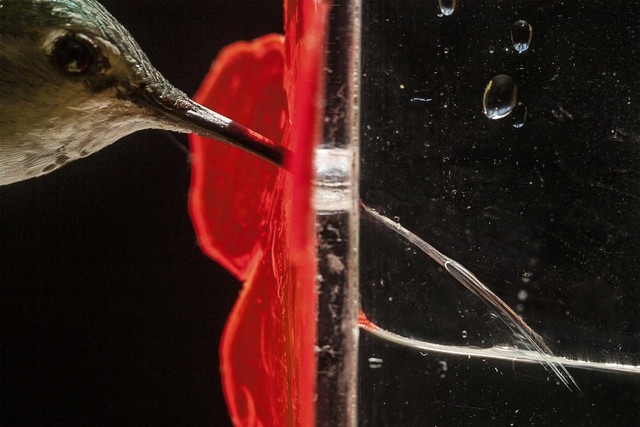

But never until the broiling summer of 2012 had he experienced such a challenge as when they set out in the backyard of their east Las Vegas home to take close-up, high-speed images that reveal how hummingbirds use their extended tongues to drink nectar.

The results, after two years of experiments and countless hours of editing thousands of frames, has left scientists and hummingbird enthusiasts alike buzzing about their spectacular photos and poetic, slow-motion film.

Their work proves that the tiny, fast-flying birds don’t suck nectar from feeders and flowers with their strawlike bills. Rather they trap it with fringe on their split tongues and draw the fluid inside their bills by moving their tongues in and out at 15 times per second.

“Filming the hummingbird out here in the July Las Vegas sun was probably the hardest photography I’ve done in more than 50 years,” Don Carroll said.

“To get enough light on the feeder so that we could get the shutter speed that we needed, we used several mirrors reflecting the sun. The temperature at the feeder would exceed 150 degrees,” he said. “We would eject the nectar, fill it up with ice-cold nectar and within a minute it would be warm again.”

They found out Tuesday that their film, “Secrets of the Hummingbird’s Tongue,” was selected from more than 600 entries to be among those featured at the seventh annual Imagine Science Film Festival. The weeklong events begin Oct. 17 at several locations in New York, including Google Headquarters, Rockefeller University and the American Museum of Natural History.

The Carrolls’ curiosity about how hummingbirds drink stems from a previous project, a book and video titled, “First Flight: A Mother Hummingbird’s Story.” They photographed the hatching of a black-chinned hummingbird’s tiny eggs in a nest of sticky spiderwebs and downy plant fibers they found balanced on a clothesline on their back porch when they moved to Las Vegas.

While they focused on eggs hatching and baby hummingbirds making their first flights, Don said, “In the back of my mind I kept saying, ‘I want to see what this tongue really looks like.’ Since the hummingbird’s tongue is in and out of its bill at 15 times a second you couldn’t see it. It’s always a blur.”

Noriko described their task: “The tiny tongue is really difficult to see inside of the nectar. You have to be so precise. So he invented various glass feeders, for close-up filming. He wanted angles never seen before.”

“The tongue kind of goes in and then comes out, and goes in and comes out. It’s so rapid that in between, we were wondering what it was actually doing. We saw at that point we have to have a slow-motion camera,” she said.

Don said experts on hummingbirds who examined their footage “were all rather shocked because most scientists are doing this kind of research in the lab, with a hummingbird in a cage under very controlled conditions.”

“We were able to get closer and sharper images. We had better lighting on it than anyone else because we shot it out in the sunlight,” he said. “We had to con the birds into coming to the feeder.”

Noriko said they had to make special see-through feeders so that cameras could be positioned for unique angles.

“He could film from the bottom, looking at the end of the tongue coming at us. This was never seen before. Don made a lot of different experiments before he succeeded,” she said.

The Carrolls also had to carry out their project to comply with the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which says it is illegal to hold a hummingbird, its nest, eggs or young, or restrain them in captivity without a valid permit. Violations carry fines of between $15,000 and $200,000.

“So you have to be very careful,” Don said. “The colleges and universities can do it, certain ornithologists can do it, researchers can do it. But we didn’t fall into any of those categories. I still wanted to see and film what was happening. So I found a way around all of that.

“We never physically touched a bird. We never did anything to the bird that could in any way harm it. So these are all wild hummingbirds in nature in Las Vegas.”

The Carrolls regularly faced unexpected problems.

“It was a little frustrating at times because it was so hot out there,” Don said. “I’ve got a wet towel over my head. Noriko has got a wet towel over her. And we’ve got the camera covered with a wet towel in order to keep the temperature down.”

There were technological hurdles, too.

“One of the things that no one understands, unless they’ve tried to do this, is that when you’re working at such very high magnification, moving something an eighth of an inch moves it like halfway across the video frame,” Don noted. “And sometimes it will take it right out of the frame and you get back there and you think everything is perfect, you’ll say, ‘What happened? Where is it?’ It’s way out on the edge of the frame.

“So you go back and adjust it again. You’ve got the instability of the camera sitting on a tripod out in the middle of the yard. You’ve got the feeder moving from the wind. You’ve got the sunlight moving. The mirrors are shaking from the breeze,” he said.

Heat also affected silicon and epoxy that were used to construct the special feeders, causing them to leak.

“You’d suddenly see the feeder just drain down, and all the nectar would come out. And then you’ve got to go in and rebuild the feeder again.”

Biologists and researchers were most appreciative of the Carrolls’ work.

In 2013, they shared some of their photos and footage with ornithologist Alejandro Rico-Guevara, of the University of Connecticut’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, who wrote back, “These are by far the best images of hummingbirds drinking nectar ever shown. Even stepping away from my biased perspective, I think the segment is really inspiring and conveys unseen magic capturing the essence of the tongue dancing with the nectar.”

Don said he hopes their work will inspire other hummingbird photographers and researchers.

“They’ll see what we’ve done and take it to the next level,” he said. “We’re just basically a steppingstone.”

For their next project they plan to use infrared photography and a loaned Olympus camera that shoots 50,000 frames per second to unravel another mystery: how hummingbirds swallow so fast.

“Over the next few years we’ll try and find a way to do this,” he said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.

Get the DVD

Signed DVDs of "First Flight: A Mother Hummingbird Story," including "Secrets of the Hummingbird’s Tongue," are available at hummingbirdstory.com for $25, which includes sales tax and shipping. DVDs can also be purchased by writing to: Concept Images LLC, 50 Radwick Drive, Las Vegas NV 89110, or calling, (702) 437-1614.