MIA: Las Vegas family still searching 40 years after Vietnam War’s end

Some Vietnam War veterans say the United States never lost the war because they didn’t surrender.

Others insist they were winning when they left Vietnam years before Saigon fell to communist forces, ending the war 40 years ago, April 30, 1975.

But for Zak Farrell of Las Vegas and the families of 1,625 other U.S. military personnel — and seven from Nevada — who are still unaccounted for, the conflict over political ideals that eclipsed three decades and cost the lives of more than 58,000 American soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen continues today.

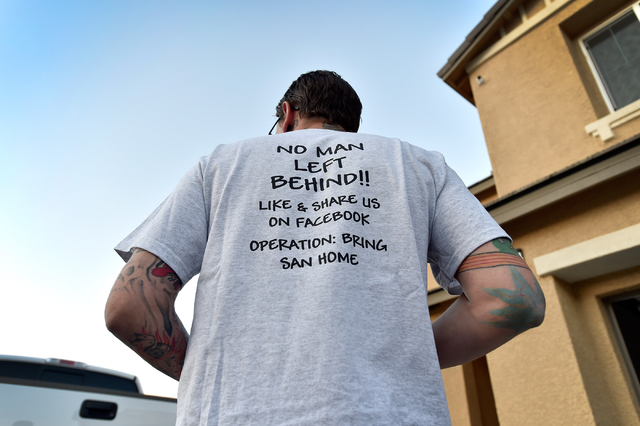

“It’s not over yet. I feel like it’s still doing damage,” Farrell, 34, said, wearing a steel Missing-in-Action bracelet inscripted with the name of his uncle, 1st Lt. San D. Francisco, and a T-shirt that shows a black-and-white photo of the Air Force pilot above the words “MIA/KIA 11/25/68 Bring Him Home!!”

“It will probably never be over because too many people lost too much during it and you’ll never ever be able to get that back,” he said.

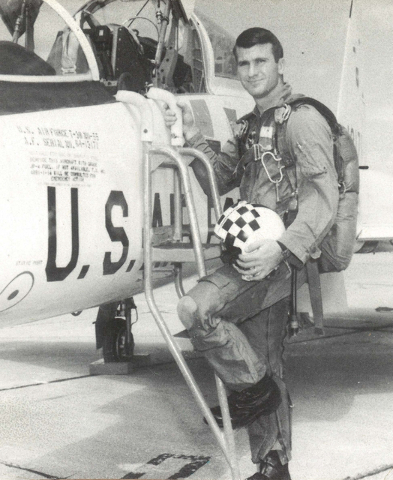

The biggest loss for him is never having the chance to know his uncle, a smart, athletic role model. His uncle grew up in Burbank, Wash., played football with a scholarship at Central Washington State College, earned his Air Force officer commission through the ROTC program in 1966 and served his country at a time when anti-war protests had divided it.

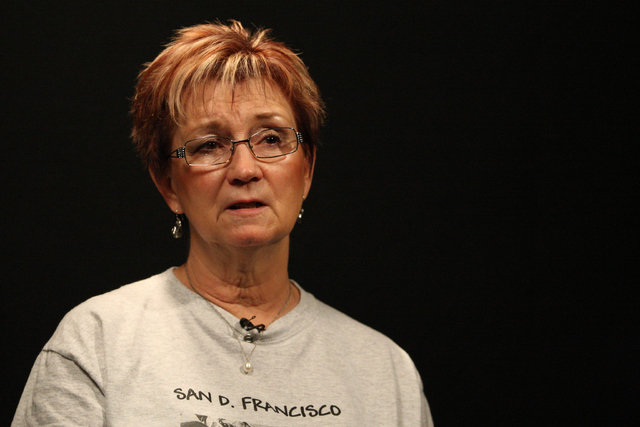

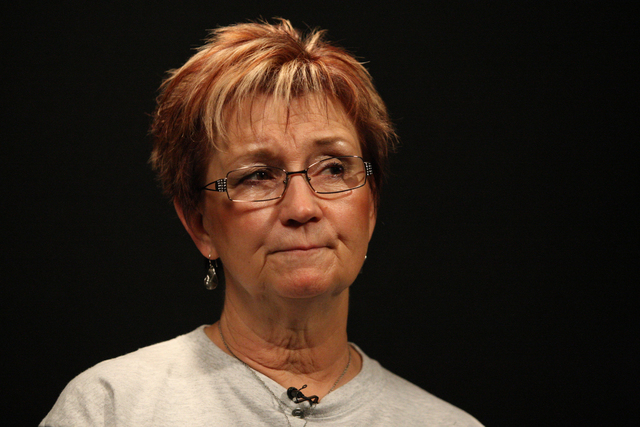

“It was a war that when he came home, he wouldn’t have been honored,” Zak’s mother, Terri Francisco-Farrell, said Tuesday after she flew from Pasco, Wash., to Las Vegas to be with her son to mark today’s 40th anniversary of the war’s end and promote her nonprofit San D. Francisco Awareness Campaign.

“Hippies, flower power, peace, love and groovy,” she said. “I was growing up in an era of anti-war, but yet my brother was over there in war. I thought he was so great he would be coming home.”

Because the war was over before he was born, Zak admits he has scant knowledge about it other than what little he learned from its mention in high school history classes.

“I can’t say I’m too knowledgeable on the Vietnam War,” he said. “I know it caused a lot of grief among people. It caused a lot of divide among people. Some people felt it was a necessary war. Others felt it wasn’t. All I can say about it is people lost a lot of family, friends, loved ones and it’s just a horrible thing.”

Regardless of ideologies on a free society and stopping the spread of communism in Southeast Asia at the time, “San,” was a “very great man, and I’m sad I never got to meet him in person,” he said. “He was just an all-around good person. If someone was in trouble, he’d be there to help them. If someone was being made fun of, he’d stand up for them. He was just the guy everyone wants to be like.”

Zak penned a letter about him in 1997 that reads: “He made everyone feel good about themselves. He was known as a gentle giant, big and strong yet polite and courteous. The class nerd was a normal person to him. “

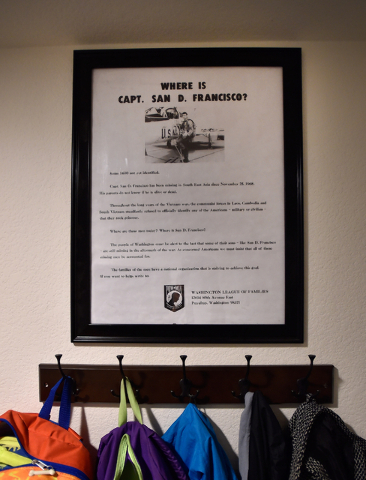

FIGHTING TO FIND SAN

Francisco-Farrell was 16 when her brother’s F-4D Phantom fighter jet was shot down over North Vietnam on a mission to escort a reconnaissance plane.

He had volunteered to fly it in the absence of another pilot, just days before he was to go on leave from Thailand to meet his wife in Hawaii.

That day, Nov. 25, 1968, farmers and North Vietnamese troops outside a village in Quang Binh province on the north-central coast saw parachutes of 1st Lt. Francisco and his backseat partner, Maj. Joseph Morrison, float down after they ejected from the crippled jet. Morrison was shot and killed while resisting capture.

Francisco broke both legs as he landed. He was being held captive when U.S. fighter-bomber jets flew over to clear the search-and-rescue area. They unleashed cluster bombs. One exploded and killed him in an open area while his captors took cover in a trench.

“He died instantly and was buried where he fell,” his sister said. Since he was the 2,000th U.S. pilot to die in the war, North Vietnamese soldiers exhumed his grave a few days later to photograph his body for propaganda.

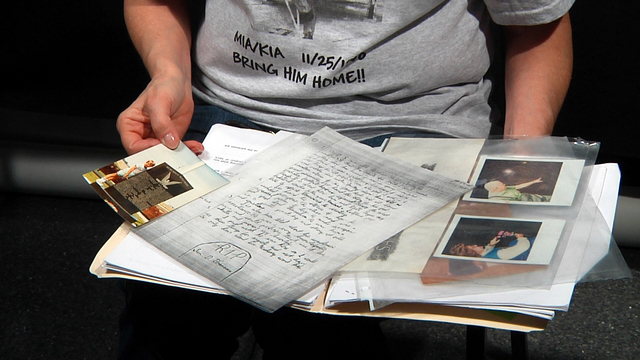

In February, nine months after the U.S. Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency produced a report on his death based on eyewitness accounts and two years after Vietnam’s government welcomed Missing-in-Action investigations in Quang Binh province, Francisco-Farrell obtained a report that unraveled the mystery that had haunted her for nearly 47 years.

She blames the Defense Department agencies for dragging their feet on investigating and recovering remains of missing service members. She said she would still be in the dark about her brother’s whereabouts today had it not been for the efforts of former U.S. Rep. Richard “Doc” Hastings, R-Wash., a family friend who traveled to Vietnam near the end of his political career to, among other things, find out what happened firsthand.

“Doc Hastings fought until he retired in November last year to get that information,” she said. “I have been briefed by JPAC (Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command) and the DPMO (Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office) for the last two years, but they’ve been vague and condescending.”

The two agencies were deactivated Jan. 30 after a revelation in Congress about their roles in scandals, mismanagement, failures to recover remains, and staging phony arrival ceremonies for bringing the remains of war dead home. The Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency now handles the tasks that the two agencies were supposed to perform.

Francisco-Farrell traveled to Washington, D.C., in June to seek the release of the investigative reports, which are supposed to be completed shortly after visits to grave sites.

“It took them a whole nine months to get that information to me, and that’s where I have a little bit of a problem,” she said.

As of today, she said her brother, who was listed in June 1978 as killed in action and promoted to major while missing, is still not on a retrieval list even though his grave site in a 20-by-40-foot area has been surveyed and marked with a painted tree at the direction of two living witnesses.

How does she feel about this?

“It makes me want to get a group of people together, get the plane, get the people, go to Vietnam — I have the coordinates. I have a map — and go get him myself instead of waiting for the government to do what it is they need to do,” she said. “They just need to go in and excavate.”

She said the Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency has a work plan. “They’ve got the map. They’ve got the two people who are still alive. One gentleman is 84. The other one is in his 70s. So the urgency of getting this done this year is imminent.”

A spokeswoman for the Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency, Air Force Lt. Col. Melinda Morgan, said Wednesday she had requested Francisco’s file to check on its status.

“Every single family member is important to us and we are working to provide the fastest possible accounting of the service member who may still be unaccounted for from past conflicts and provide it to the families,” Morgan said.

VIETNAM VET’S VIEW

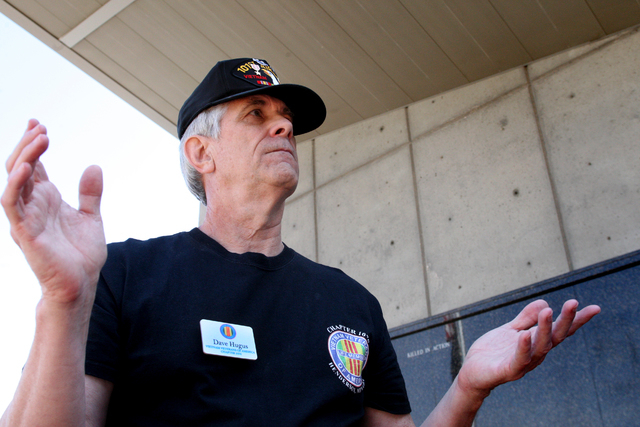

Vietnam War Army veteran Dave Hugus said having a loved one missing in action “is the worst thing that can happen to a family. It condemns them to infinite uncertainty.”

Like Francisco, Hugus, a member of Henderson’s Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter 1076, received his Army officer’s commission in 1966. That was after graduating from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind.

Now a retired lieutenant colonel, Purple Heart recipient and decorated infantry combat commander, he served two tours in Vietnam, first with the 101st Airborne Division in 1968.

Then after nearly bleeding to death from a grenade strike that pulverized his knee, he defied a doctor who thought it would be best to amputate his leg. Instead he recovered, passed physicals and combat training requirements and returned to Vietnam, serving with the 25th Infantry Division in 1970-71.

He knows pain and sorrow from the loss of many comrades in his units, and he endured the days when Vietnam vets were shunned by the public and even other veterans groups.

“Unfortunately the 40th anniversary is a much better anniversary than the 10th or the 20th,” he said, standing in the shadows of the veterans walls outside Henderson City Hall.

“For some reason in the Vietnam War, the public climate was so anti-government, so anti-authority that anybody who was associated with the government even as kind of an innocent participant was put in the government box,” he said.

“So there was this failure on the part of the American people to differentiate between their disagreement with the foreign policy of the United States and those people who were charged with the execution of that policy.”

Public support for veterans has swung like a pendulum since World War II, going from positive to neutral during the Korean War to negative during the Vietnam War and back to positive for post-9/11 operations that had a halo effect for recasting Vietnam-era veterans in positive light.

In Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq “we’re not dealing with a military problem. We’re dealing with a political problem that has a military component,” he said.

As for the Vietnam War, Francisco-Farrell said she’ll be thinking today about it “not being the end for a lot of families, and thankful that it did end.”

For more information about Francisco-Farrell’s “Operation: Bring San Home,” and how to donate go to www.sdfawareness.org

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.

Related

Las Vegas veterans’ thoughts on Vietnam War anniversary