Billy Walters, the ‘Michael Jordan of sports betting,’ tells all in book

Chicken or feathers.

That was the working title for Billy Walters’ autobiography, “Gambler: Secrets from a Life at Risk,” which will be released Tuesday.

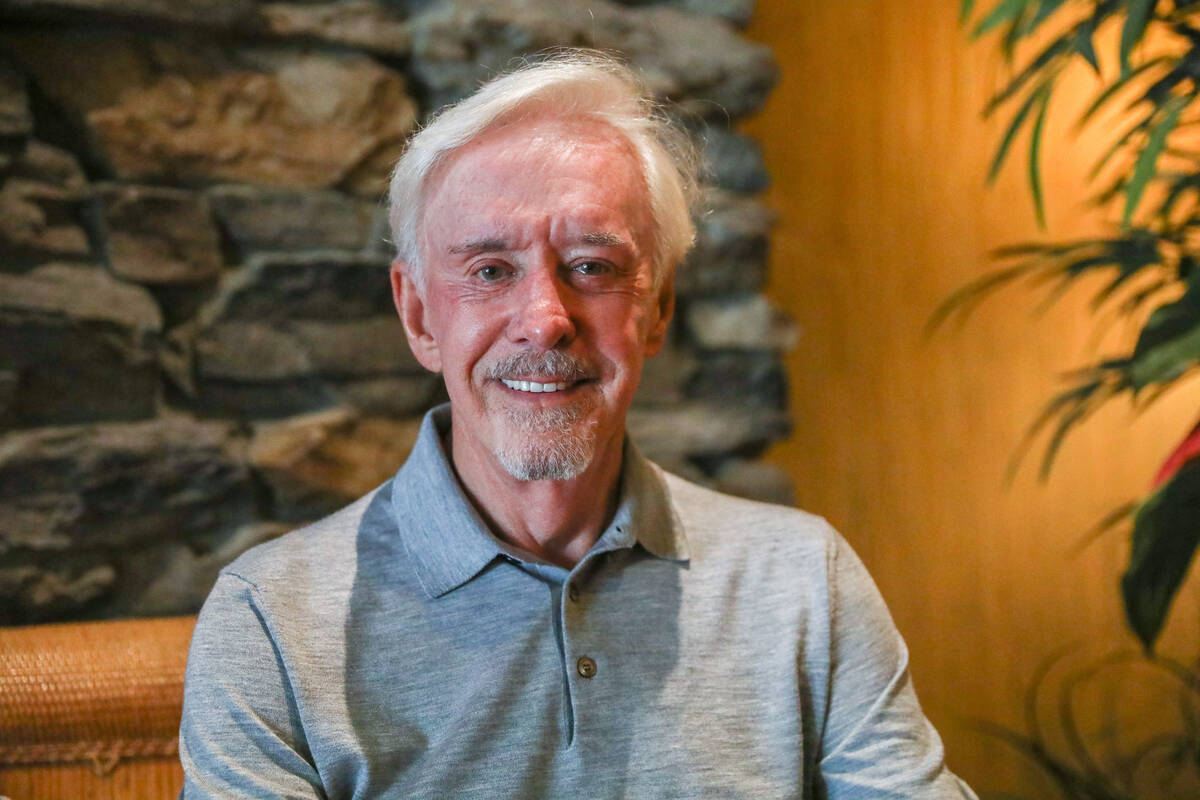

“That’s a gambler’s life. You’ll have good days and it’s chicken, and you’ll have bad days and it’s nothing but feathers,” Walters told the Review-Journal during a recent interview at Bali Hai Golf Club, which he owns. “I’ve had more ups and downs than most.”

The Las Vegas businessman and philanthropist is widely regarded as the most successful sports bettor of all time.

“Billy Walters is the Michael Jordan of sports betting,” South Point sportsbook director Chris Andrews said. “He won more than anybody.”

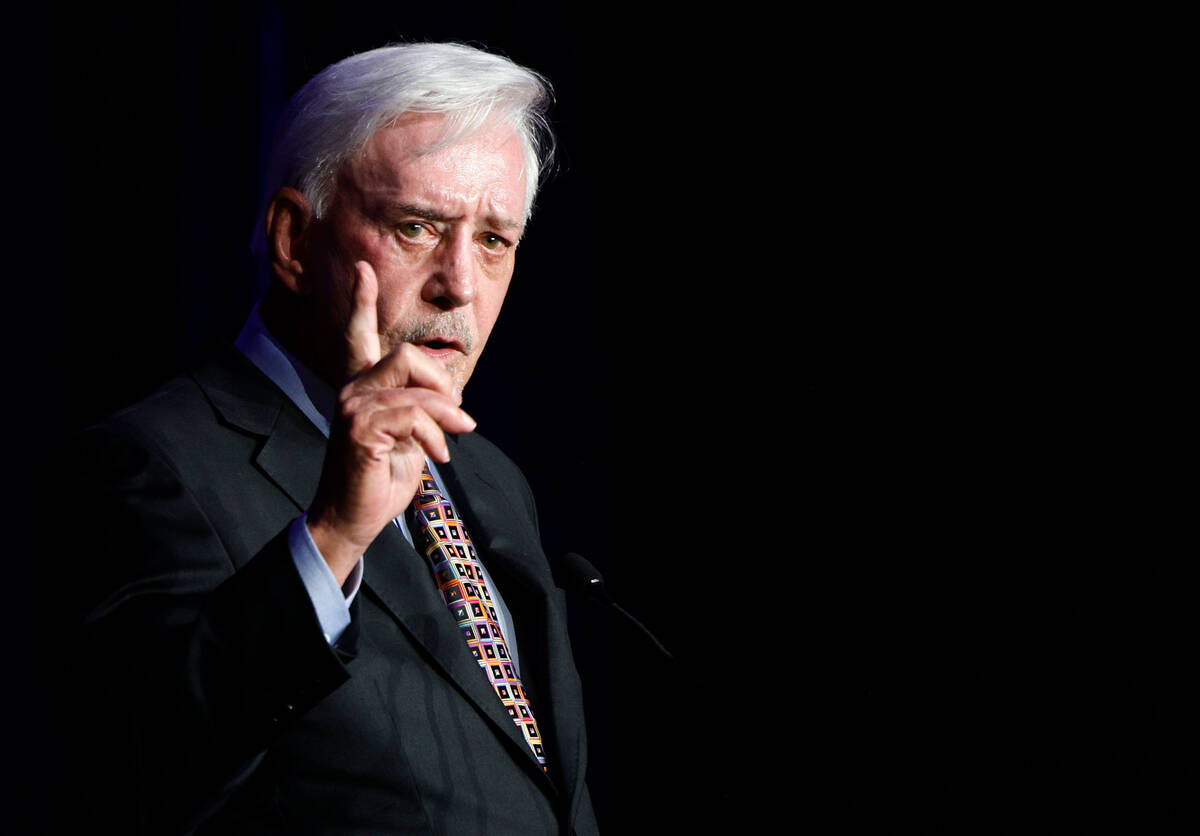

In the book, written with Armen Keteyian, Walters gives an unvarnished account of his rags-to-riches life story and takes readers on a wild ride inside the world of high-stakes gambling.

Walters has bet billions of dollars and won hundreds of millions since the 1980s, when he became a member of the Computer Group — acknowledged as the first syndicate to apply sophisticated algorithms and computer models to sports betting.

Born into rural poverty in Munfordville, Kentucky, and raised by his grandmother in a one-bedroom rental with no running water, Walters recounts beating addictions and surviving beatings, armed robberies and shakedowns by mobsters, as well as being indicted six times and serving 31 months in prison while dealing with personal tragedies after he was convicted of insider trading.

Walters also discloses explosive details about his relationship and betting partnership with pro golfer Phil Mickelson.

Walters writes that Mickelson wagered more than $1 billion on sports the past three decades, his gambling losses approached $100 million, and he tried to place a $400,000 bet on the Ryder Cup.

Walters also writes that he believes he could have avoided prison if Mickelson had testified at his trial. Walter’s daughter died by suicide while he was imprisoned, and he writes that he “could have saved her if I’d been on the outside.”

After decades of fiercely protecting his proprietary sports betting system during an unprecedented 36-year winning streak, Walters finally reveals the secrets to his success in granular detail in a master class for sports gamblers.

He said he felt compelled to write the book after he got out of prison. He was released in May 2020 to serve the remainder of his five-year sentence at home because of the coronavirus pandemic. His sentence was commuted by then-President Donald Trump on his final day in office on Jan. 20, 2021.

“There were a number of motivations,” Walters, 77, said. “I’m not getting any younger. I love gamblers, and now that my dream has come true with legalized gambling throughout the United States, I want to share everything I know about sports betting and gambling with the world.

“I wanted to share my entire life because I know I can help a lot of people. I’ve had addictions. I’ve been up. I’ve been down.”

‘The Kid’

Walters wrote that he was just 18 months old when his father died and his mom left town, leaving him and his two sisters with relatives.

“I was lucky. I caught the lottery,” he said. “I could’ve had four parents and I couldn’t have had a better role model than my grandmother.”

When his grandmother went to work, she left him at his uncle Harry’s pool hall, where he became an accomplished pool hustler by age 10 and was known to locals as “The Kid.”

Walters said he didn’t know what he wanted to be growing up. But, looking back, it was apparent.

“I wanted to be successful, I knew that,” he said. “At 7, 8, 9, 10 years old, I knew that gambling and risk-taking was going to be part of my life. It was something I enjoyed and I loved.

“I guess I should’ve known then — I wanted to be a gambler.”

He made his first sports bet at age 9, when he lost $125 to the town grocer on the New York Yankees to win the 1955 World Series. It was all the money he had saved from two years of mowing lawns.

“But that first betting loss on sports didn’t turn me off from gambling. Just the opposite,” he wrote. “The thrill of having all my money on the line was nothing less than addictive.”

Go for broke

Walters — also a golf hustler who in addition to sports betting has made hundreds of millions in the stock market and business, owning 13 golf courses and 22 car dealerships at his peak — wrote that he earned the equivalent of a $500,000 salary in today’s dollars at age 20 as a car salesman.

He sold an average of 32 cars a month in 1966, when he made $56,000, and his record was 56 cars in a month.

But Walters was a self-described “heavy drinker, chain-smoker, and a gambling addict with a capital A” who lost money as fast as he made it. He went broke about 200 times, losing his $50,000 house in a card game one night.

“I never had any fear of losing,” he said. “I never even thought about getting broke because I knew eventually one day I was going to be successful. When I got broke, that was part of the pursuit.”

He came to a crossroads in his life in Louisville, where he was arrested for bookmaking. He could stay in Kentucky and get back into the automobile business. Or he could move to Las Vegas and become a professional gambler.

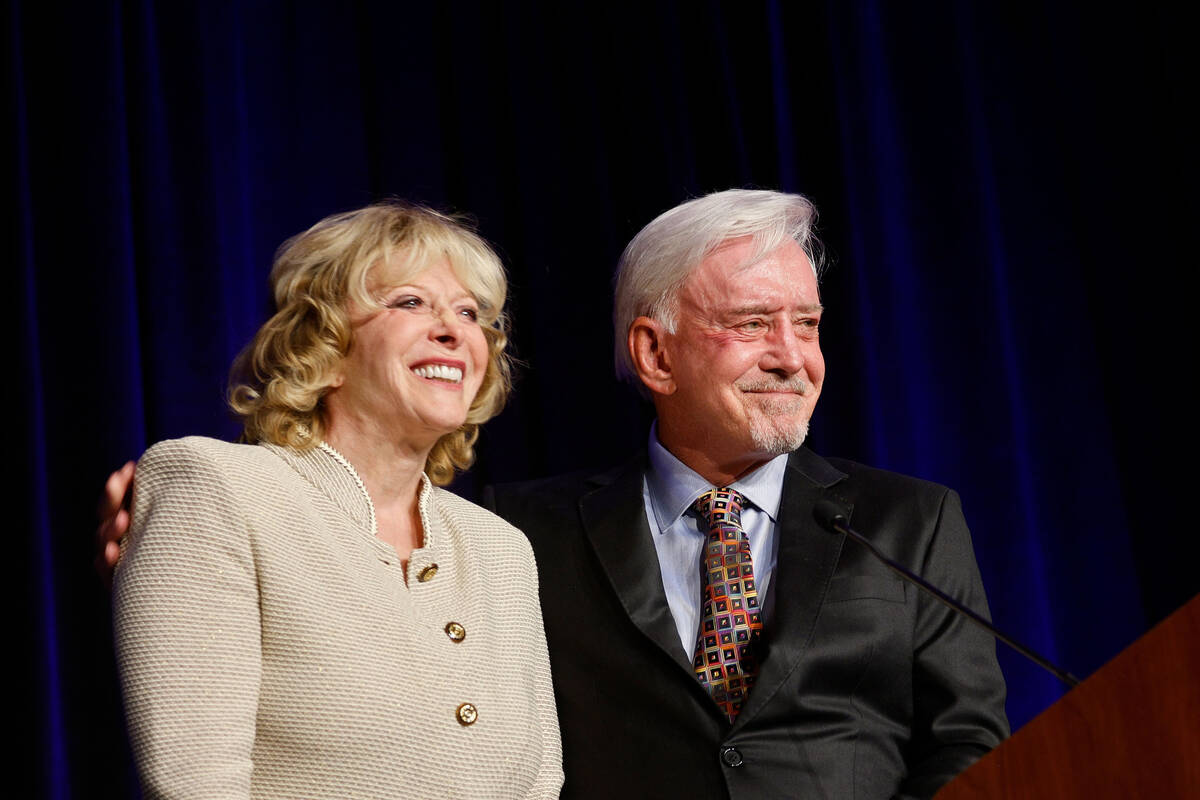

At the time, Walters said he and his wife, Susan — who have been married for 46 years — might have been the only people in the world who thought he would be successful. His friends gave him zero chance.

“They posed a simple question,” he wrote. “What are the odds that an alcoholic and degenerate gambler with no money management skills could survive in a city that ate addicts for lunch and dreams for dinner?”

Walters was $300,000 in debt and facing felony charges in Kentucky when he moved to Las Vegas in September 1982.

But he had an ace up his sleeve in the form of the Computer Group, which he had placed bets for in Louisville.

‘Cooking with gas’

“I was a handicapper in Kentucky, but I was a pencil-and-piece-of-paper guy,” he said. “I knew that I was cooking with wood, and they were cooking with gas.”

Michael Kent was a math and computer wizard who wrote the code that launched the Computer Group. His regular job was developing nuclear submarine technology at the Westinghouse Electric Corporation in Pittsburgh. After initially producing power ratings for the company softball team, Kent wrote a computer program to predict numbers on football games against the Las Vegas line.

Within three years, Kent was betting $50,000 a week on the NFL through a network of friends that helped mask his identity from wary bookmakers.

When Walters joined the group in Las Vegas, his job was to move millions of dollars in wagers through an intricate global network of runners and beards while protecting the Group’s identity.

“He put together an amazing logistics outfit that he could bet anywhere at the same time,” longtime Las Vegas oddsmaker Michael “Roxy” Roxborough said. “Not just in Nevada, but around the world.”

The Computer Group won $25 million in one year — almost $70 million today — according to a 1986 Sports Illustrated cover story on gambling.

Million-dollar losses

But Walters was still fighting his demons. Following a dinner at the Horseshoe with his wife to celebrate having $1 million in their bankroll for the first time, he lost $1.2 million during a drunken blackjack session. It was a familiar pattern.

After attending Benny Binion’s 80th birthday party, an inebriated Walters lost $1 million in a single session at his casino.

“Then I won $2 million betting sports and went back to the Horseshoe — tell me if you’ve heard this story before — and got drunk and lost that, too,” he wrote.

It wasn’t until 1989 that Walters, shaken by the death of his close friend, poker pro Fred “Sarge” Ferris, quit smoking and drinking. Cold turkey.

“Since I quit drinking, I’ve played a lot luckier,” he said. “That’s one of the major reasons I’ve achieved financial success.

“But make no mistake about it, whatever success I’ve had, it would’ve never happened if I hadn’t been married to Susan Walters. She’s made a much better man of me.”

Organized betting

The FBI began investigating the Computer Group in 1984 for illegal bookmaking. Walters was charged but acquitted. He also beat three other similar indictments in Nevada.

“When I came to Las Vegas, there’d never been an organized group of bettors,” he said. “… Up to that time, the only people law enforcement saw organized were bookmakers, and many of them were affiliated with organized crime. We weren’t. But because of the size of what we were doing, we were misunderstood.”

After the demise of the original Computer Group, Walters started his own syndicate in the mid-1980s.

“I realized that eventually the line was going to catch up with what we were doing, because the advantage was narrowing every year,” he said. “That’s when I decided to get involved with multiple people such as Mike Kent and get independent pieces of information.

“I was able to combine things, kind of similar to what hedge funds do, or a guy like Warren Buffett does. He looks at lots of different pieces of information from different analysts and then he decides what he wants to do.

“That’s what I started doing in 1985, 1986, and that’s what I’ve done since then. That’s the only reason I’ve been able to be as successful as long as I have.”

On a busy college football Saturday in his heyday, Walters wrote that he would orchestrate $20 million in wagers worldwide on about 150 games and tap into more than 1,600 betting accounts while hiding his identity.

“Everyone was trying to steal his plays,” bookmaker Nick Bogdanovich, now Circa sportsbook manager, said.

Market mover

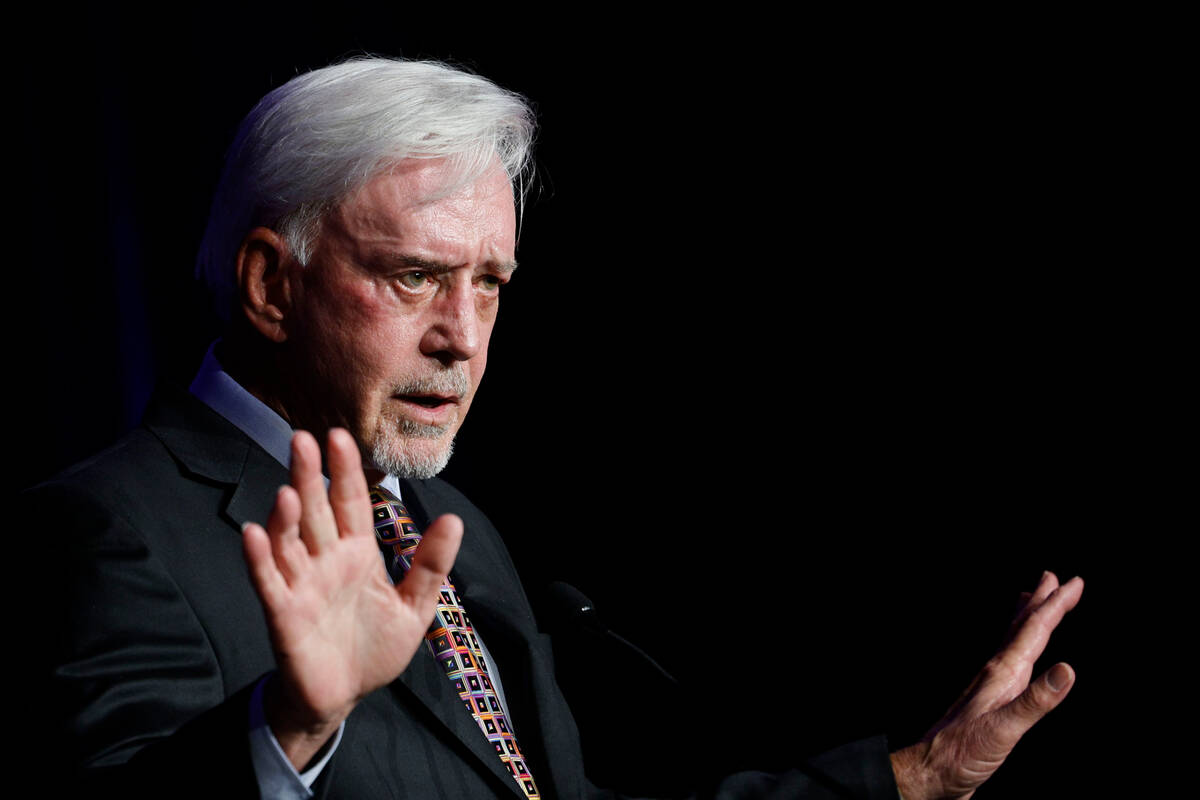

Walters became a master at moving the line, which he said stemmed from his need to counteract the countless bettors who have tried to shadow his gold-plated picks over the past five decades.

To confuse his followers, he would throw head fakes. For example, in the morning he would bet a 6½-point favorite and everybody would wager on it, causing the line to climb to 7½. In the afternoon, Walters would come back and hammer the underdog at the better number.

“I moved the line a lot. But I was kind of forced to do it,” he said. “I would have bookmakers that I would bet, and the second I would give him the bet, they would have three or four guys in the office trying to bet all the bookmakers they could bet. As a result, the line would move or places that I was wanting to go bet, I couldn’t bet.”

“So I would go in and give him the opposite side, and I’d let him bet all these other guys and I would turn around and bet everyone in the world on the other side.

“I had the same issues, unfortunately, with a lot of partners that I had, because the agreement with all of them was that you can’t tell anyone who you were betting on and you’re not allowed to bet on the games. I would go into accounts and I would bet them, and my partners would see who I bet on and they would sneak over and bet. … So I would go into their accounts and I would put bets in there on the wrong side. For the same reason. … I did those things to teach lessons.”

Walters’ 36-year winning streak — which included a $5.5 million windfall on the Saints winning the 2010 Super Bowl — came to a halt in 2017, when he had to prepare for his insider trading trial.

When he got out of prison, he said it took a year to update his computer program before he started betting on sports again.

“For as long as I live,” Walters said. “I’ll bet on sports.”

Contact reporter Todd Dewey at tdewey@reviewjournal.com. Follow @tdewey33 on X.

Walters to donate proceeds from book to charities

Billy Walters' son Scott was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor at age 7. He survived but was left brain-damaged.

Having a disabled son has led Walters to donate millions of dollars to charities, including Opportunity Village. He plans to donate all of his net proceeds from his autobiography, "Gambler: Secrets from a Life at Risk," to the home for intellectually disabled people in Nevada, as well as the Cedar Lake Foundation in Louisville and the Hope for Prisoners Billy Walters Center for Second Chances in Las Vegas.

"If you're fortunate enough to be successful in life and you don't give something back to help others, I think you're making a huge mistake," Walters said. "That's one of the things that I get more fullfilment from than anything."