‘Machete Squad’ graphic novel tells of Las Vegas vet’s service in Afghanistan

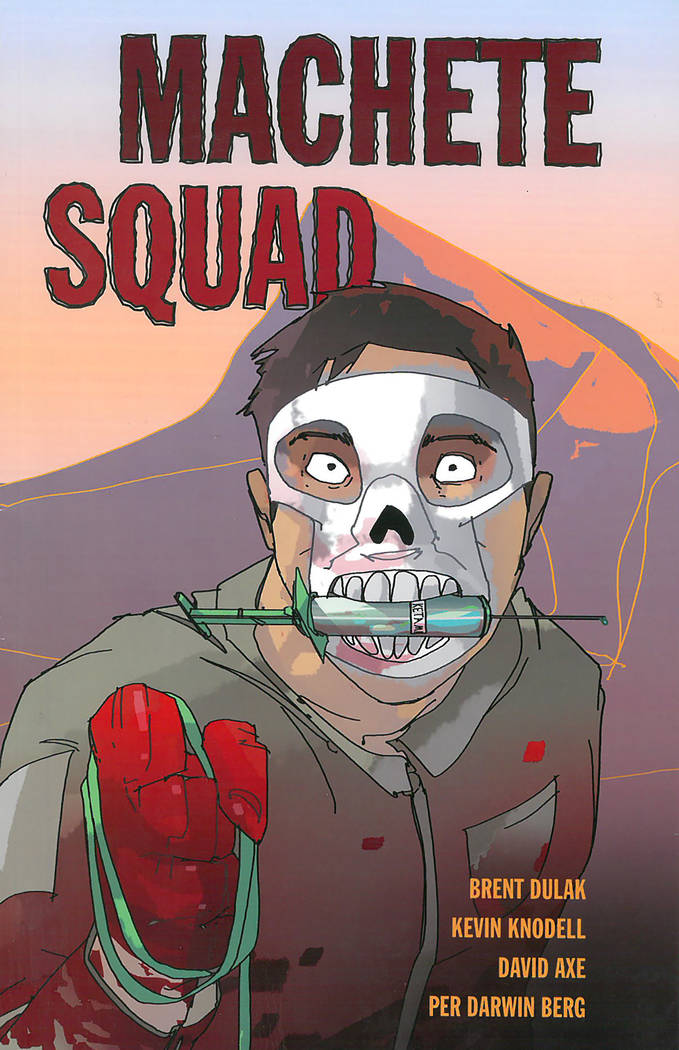

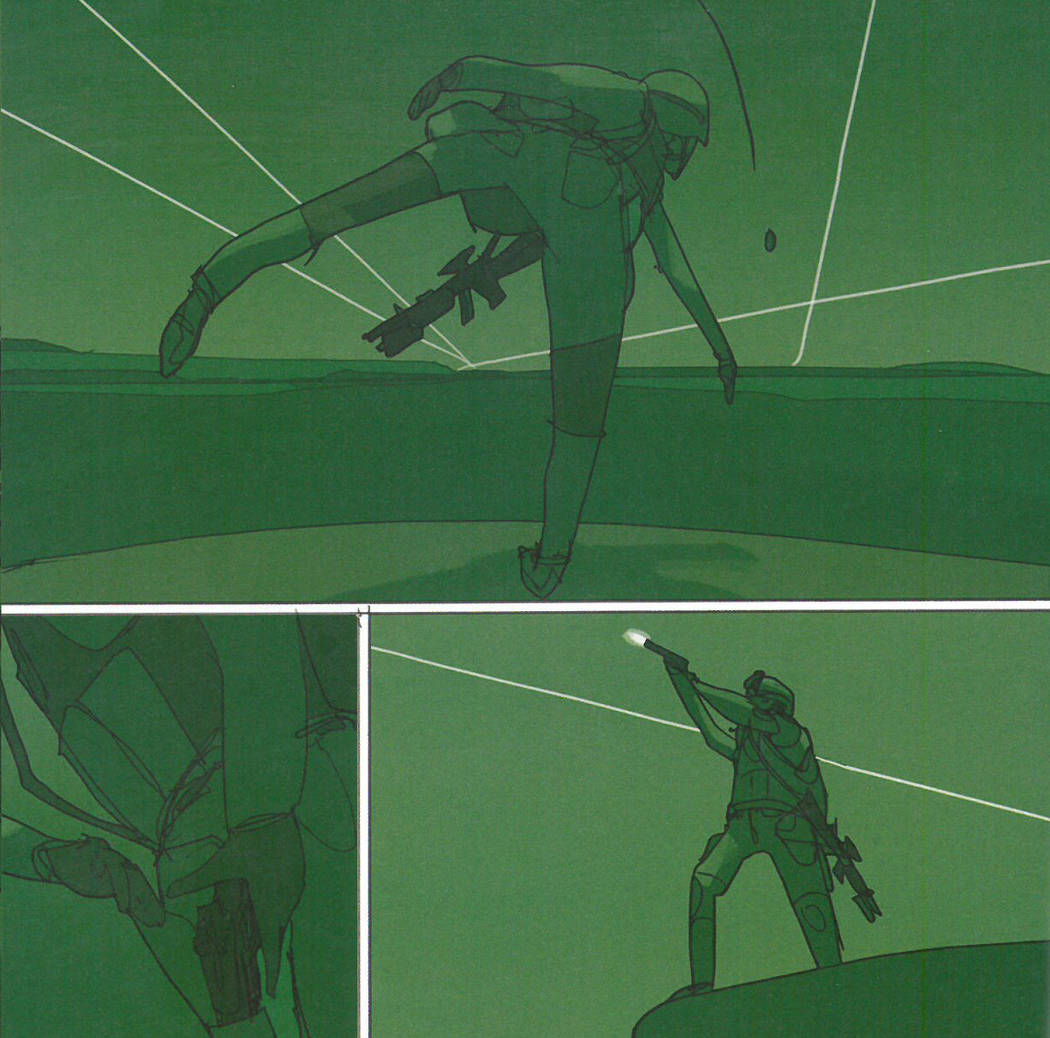

It’s not surprising that “Machete Squad,” a graphic novel about Brent Dulak’s experiences as an Army combat medic in Afghanistan, would be intense.

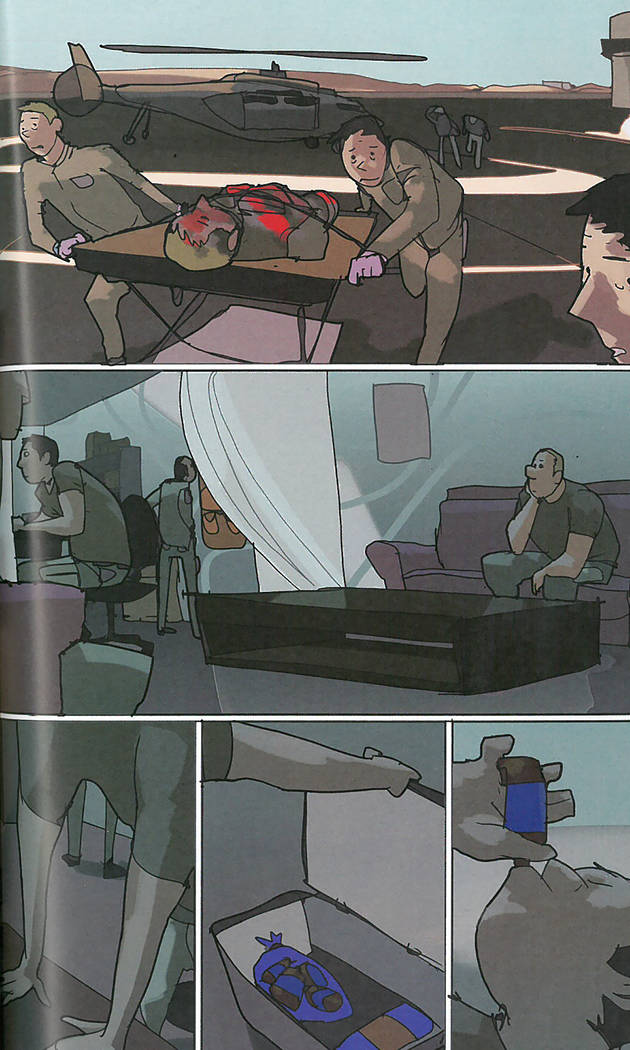

The book does have scenes that depict combat and the bloody chaos of an aid station. But just as brutal are a few pages at the beginning — the ones that show a soul-deadened Dulak before he ships out — that illustrate the emotional violence of war.

Today, Dulak is a physician assistant who works in the emergency department of University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. “Machete Squad” ($18.95, Dead Reckoning) is based on journals he kept during his deployment to Afghanistan from 2012-13.

Before Afghanistan, Dulak twice had been deployed to Iraq. “I struggled a lot with coping with my first two deployments,” he says. “I’ve always loved to write, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. So I kept a journal to kind of help me process everything I was going through.”

‘Only way out’

Dulak, 34, had no great desire to be a soldier. The Wisconsin native enlisted at age 21 mostly to get his life on track.

“I ran with a bad crowd when I was younger,” he says. “I got into juvenile trouble and made stupid decisions and didn’t think things through. It was that classic case of, ‘You’re wasting your potential.’

“It got to the point where I was making windows 60 hours a week, drinking when I wasn’t working, and just generally wasting away. Things were just deteriorating.

“I was never ‘Rah-rah, let’s run off to Iraq to fight a war,’ ” Dulak says. “But I knew it was my only way out.”

Nor did he have any desire to go into medicine. But while waiting to sign his final papers at the military entrance processing station, “they had ‘Saving Private Ryan’ on the big-screen TV in the lobby,” he says. “Every time I saw the movie, I loved the medic.

“So I went in, and he asked me what job I want, and I said, ‘How about combat medic?’ He says, ‘Easy.’ ”

Iraq

Dulak left for basic training on Dec. 27, 2005, the day he turned 21. He then received additional training as a combat medic specialist and served stateside in Texas until his deployment to Iraq from 2007-08.

“I was with a medical unit so I wasn’t going to be going off on missions and things like that,” he says, although the base “got mortared almost every single day.”

But adjusting to the stress and the routine was difficult, and Dulak began to to experience what he now recognizes as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It’s hard, especially if you’re there so long,” he says. “You lose all concept of time because you’re detached from what your life used to be and you become detached from who you are as a person. You just lose yourself.

“PTSD is real. It doesn’t matter whether you’re shot at. I had it after 15 months on a base where we had a Burger King across from the housing area.”

Still, Dulak re-enlisted for a six-year hitch when his initial contract ended. The recession had hit, the housing market had collapsed, and, he says, “I knew if I got out right now I was just going to go back to what I was doing before.”

Dulak again was deployed to Iraq, this time for a 12-month stint, from 2009-10. Again, it was “a relatively simple deployment,” he says, despite going on patrols, facing “the ever-present danger of IEDs, and continuing to ignore PTSD.

“I never stopped and thought I had PTSD,” he says. “It was just like: ‘Oh, I guess I’m just an angry guy, I’m just that guy that sucks at relationships. I’m that very angry guy who sucks at relationships. That’s just my personality. I don’t have PTSD.’ So, you kind of kid yourself. Or maybe at the time I wasn’t really aware.”

Afghanistan

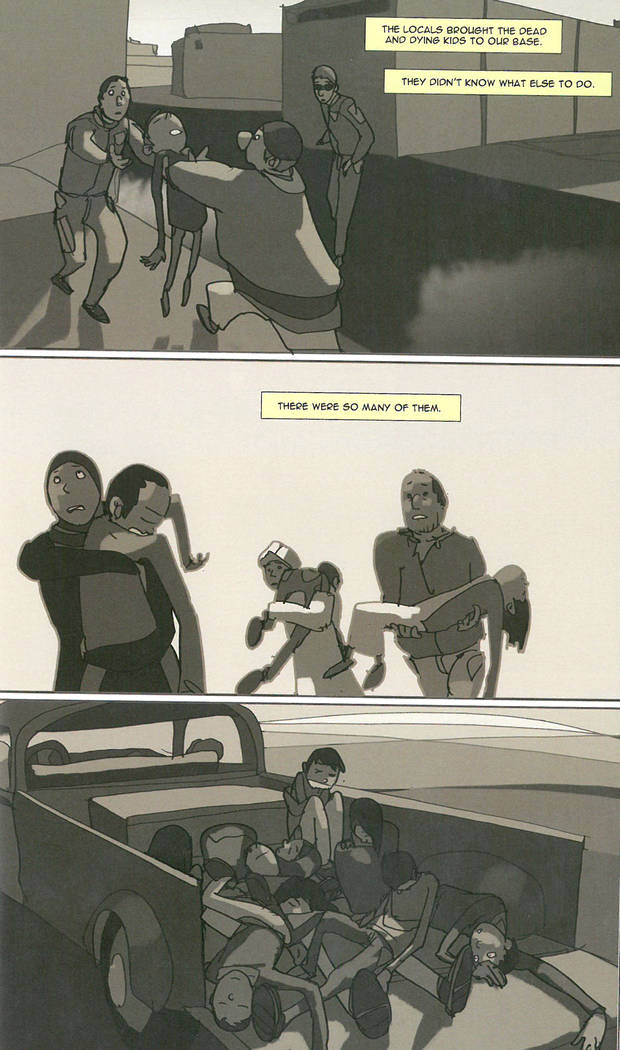

In 2012, Dulak was sent to Afghanistan’s Kandahar province for a nine-month deployment to a combat outpost at Sperwan Ghar. For several weeks, Dulak — now a sergeant commanding his own squad — had been receiving reports of high casualties from the squad his was to replace.

“Just hearing the reports, oh crap, this is going to be very, very rough,” says Dulak, who was continuing to self-medicate through “drinking, women and just living a life that’s not healthy.

“I was spiraling pretty hard. I was convinced I was gonna die.”

That deployment marked “the first time I was ever shot at,” Dulak says. “There’s a scene in the book where I step outside to smoke a cigarette and I hear a swarm of bees, and it’s bullets going overhead 24/7.”

Dulak called his unit “Machete Squad,” taken from the adult cartoon series “Frisky Dingo” and meant to serve as a means of building camaraderie. It also served as an oblique reference to the brutal intensity with which his squad worked.

In Afghanistan, Dulak finally acknowledged PTSD, reaching “full awareness that there’s something else going on (and) I’m not just the angry guy.”

Yet, the memories that first surface when he thinks of that deployment are of “small things, like the first night they brought tacos to the dining facility.

“That night was amazing. We all sat down on a couch inside the aid station and I felt a high from so many endorphins running in my body. It was the most content and satisfied I ever felt in my life.”

Coming home

Dulak returned to the United States with about nine months left on his contract. But, he says, “I knew it was the end.”

“I didn’t want to keep pushing my luck,” he says. “It was time to move on. There was nothing more in the military I wanted to do at that point. It was just gaining rank and going into more administrative kind of roles, and I really didn’t want to do that.

“More important, I wanted to be in control of my life. I wanted to be the one to make decisions, to know this is what I was going to do today. Maybe it’s working out at 6 in the morning, maybe it’s getting four breakfast sandwiches at McDonald’s and going back to bed. I wanted to be able to have control of my life which, in the military, you just don’t.”

Dulak became a physician assistant in 2017. He had been in the Army from ages 21 to 28, and has noticed that when he looks on social media and sees “people in their 20s, I feel they’re doing so much more than I ever did. I’ve never seen beaches in Bali. I’ve never visited Europe, other than getting off a plane. I feel (at) a certain part of my life I just missed out on so many experiences.

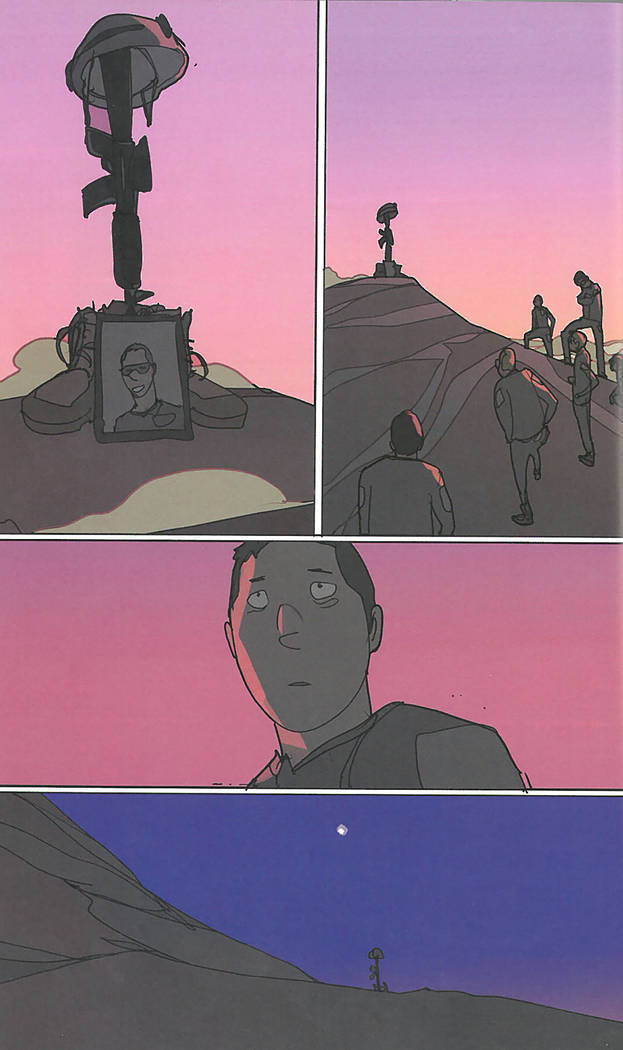

“Now, I can look at it from a different perspective. I have hiked on mountains no one I know will ever hike on. I’ve seen sunsets no one will ever see. I’ve seen places no one in America will ever go to, which is tragic because (they’re) so beautiful.”

“Looking back, I’m very grateful for my time in the military,” Dulak says. “I’d be nowhere near where I am today if I never joined the military. But it ended, and I wanted to go forward and do better things and help others.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.