Like Las Vegas, Miami battles onslaught of squatters

MIAMI — After a huddled briefing outside a strip mall, the convoy of Miami-Dade cops drove to a grimy-looking house and moved in, guns drawn.

One carried a semiautomatic rifle, another a shield, and another a sledgehammer.

Their target? Squatters.

Las Vegas has grappled with a widespread squatter problem in recent years, a lingering side effect of the housing crash. But it’s not alone: Squatters also took over vacant homes throughout the Miami area, a fellow poster child for the real estate boom and bust.

In many ways, their situations have been all but identical. Squatters in both areas have routinely shown fake leases to police, claimed to have found their house on Craigslist, operated fraud labs, and followed or been linked to people with anti-government “sovereign citizen” ideology. They’ve also used or sold drugs, trashed the place and stolen or lacked utility service.

Squatting is not unique to Las Vegas and Miami, and, like any crime, will almost surely persist, as long as there are abandoned properties for the taking. But Miami’s experience shows that Las Vegas isn’t the only one to have dealt with this dark aftermath of the housing bust even as the economy improves, and that officials outside Nevada have taken other steps to crack down.

Perhaps the biggest difference: Miami-Dade police operated a full-time squatters unit for more than three years, where Las Vegas police, who have reported “vast increases” in squatter-related service calls, haven’t formed one and don’t plan to.

A number of people in South Florida say the squatter problem isn’t as bad as it used to be, amid sharp drops in foreclosures and underwater borrowers and a rebounded housing market. But squatters still move in.

Miami city police Detective Jesse Henriquez, the department’s one-man squatter detail, said he’s worked on more than 100 cases in the past 2½ years and still knows of “squatter brokers,” or people who drive around neighborhoods, often in luxury cars, to find empty homes and rent them out.

The Miami-Dade Police Department, which works unincorporated and other areas of the county, scrapped its dedicated squatter unit in January, police say. But it still handles cases through its economic crimes bureau, and Detective Danny Garcia said his squatter workload hasn’t changed the past few years.

“We were just given 10 cases this morning,” he said recently.

And, as police and real estate pros know all too well, such homes can spiral into a mess of problems.

Miami-Dade police encountered a house where squatters were growing marijuana on the first floor and operating a strip club on the second.At another, they arrested a high priest of Santeria, an Afro-Caribbean religion, who had draped a chain link across the threshold of a door to block evil spirits from entering.

There also was a squatter house where mixed martial arts fighters were training – and selling weed and crack on the side. The police brought the SWAT team for that one.

‘To me, that’s illegal’

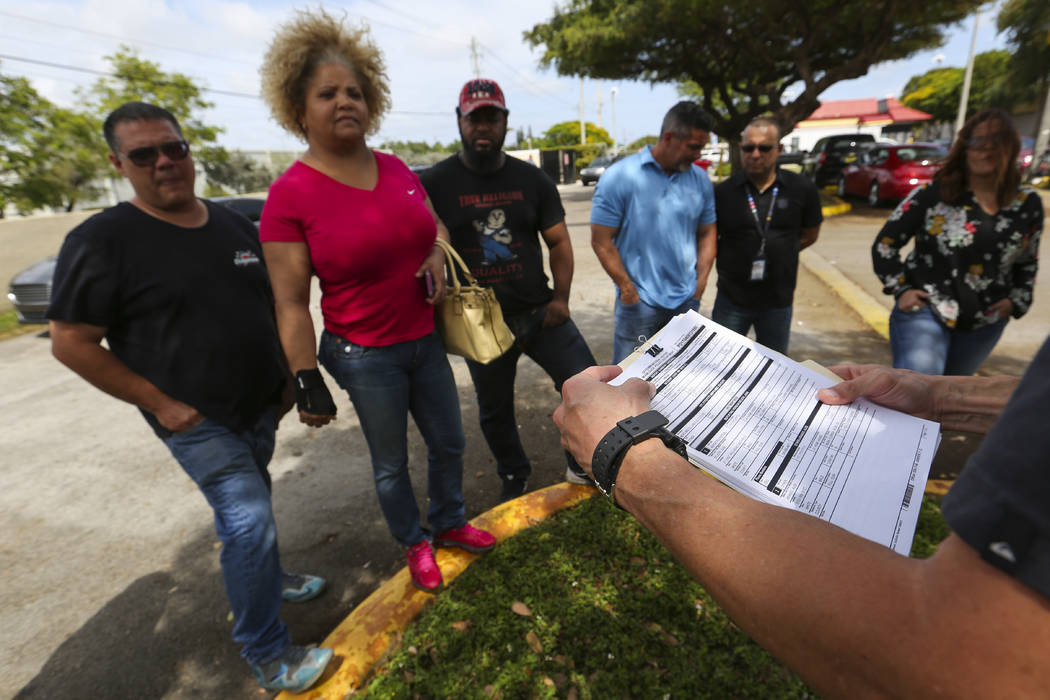

In a strip mall parking lot in northern Miami last month, Garcia was going over paperwork. Joined by 10 or so other Miami-Dade cops — including undercovers and a muscle-bound, minivan-driving lieutenant – he introduced them to the owners of the house they were targeting and noted that six people were reported to be inside. One, he said, had a name that was popular with sovereign citizens.

When they drove down the street to clear the house that day, three people were inside – a man, a woman, and the woman’s son, who looked about 5 and ran into her arms.

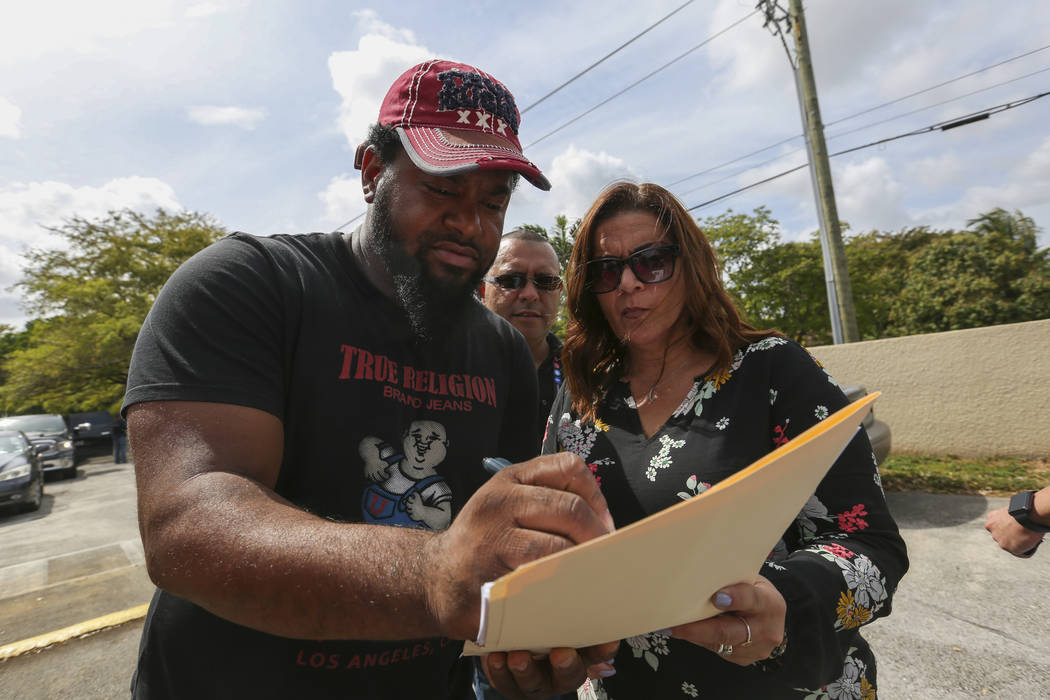

Police say they found two inflatable mattresses, a generator, and a kitchen without a stove or refrigerator. But the squatter removal wasn’t as simple as they thought, as the man came out holding an adverse possession claim.

Adverse possession laws can let people take ownership of abandoned real estate, but with strings attached. In Florida, they include paying back taxes as well as the property taxes for the next seven years.

Claims soared in South Florida after the market crashed. Sovereign citizens — known for financial scams, nonsensical writings and occasional violence — were among those making claims, according to police and Lazaro Solis, deputy property appraiser for Miami-Dade County.

“I’ve been working for this office for many years, and I only heard about (the law) when it actually flared up,” Solis said.

Coral Gables passed an ordinance in 2013 that defined squatting as occupying a property without the owner’s or tenant’s consent. As City Attorney Craig Leen sees it, if someone claims adverse possession, they’re all but admitting to being a squatter.

“Someone shouldn’t break into someone else’s house to live there,” he said. “To me, that’s illegal.”

Tactical teams

Some local governments in South Florida still treat squatting as a civil matter, according to Pedro Realty International owner Liza Mendez. That used to be the common response from police departments, but Miami-Dade’s was the first to go after squatting in an organized way, said Danielle Blake, senior vice president of housing and government affairs for the Miami Association of Realtors.

It launched a dedicated squatter task force in 2013. The group did undercover work, started a database to keep track of homes they targeted and were helped by an in-house analyst who researched the properties, police say.

When it came time to get squatters out, officers went in tactically, setting up a perimeter at the house, pulling their guns and issuing loud commands, said Sgt. Marisol Garbutt, who used to run the squad.

“There is no shortage of criminals or illicit activity … and we never know, going into these homes, we don’t know what’s happening on the other side of that door,” she said.

Miami-Dade police said last month that the department had stopped operating a full-time squatters unit and shifted detectives to a team that handles mortgage and condo fraud. Asked why, they did not give any reasons.

In a statement to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, economic crimes Lt. Carlos Gonzalez disputed the notion that the squatter unit was disbanded, saying its detectives were “reallocated” to a different squad and given “additional responsibilities” for real estate and financial crimes.

They still mainly investigate squatter cases, Gonzalez added. But he, too, did not provide any reasons for the change.

Nevada lawmakers and local officials have taken various steps to crack down on squatting in the Las Vegas area, whose housing market also is on stronger footing. Still, the Metropolitan Police Department received almost 5,400 squatter-related service calls last year, up 73 percent from 2014, as well as 148 squatting-related police reports.

Metro handles the cases through its area commands and has no plans to form a dedicated squad, said Officer Michael Rodriguez, a spokesman.

He said the department looked into starting one but added cases can lead to lengthy investigations involving multiple suspects, property and legal records, and landlord-tenant laws. He also noted Las Vegas was hit with a record amount of violent crime last year, a more pressing matter for Sheriff Joe Lombardo.

Metro investigated 168 homicides last year, the most since at least 1990.

“We simply don’t have the manpower right now to create a squad specifically designated to tackle the squatter problem,” Rodriguez said.

Garbutt said it was helpful to have a dedicated team. As she described it, quality-of-life issues were the top complaint — squatters would steal water or electricity, for instance — and the squad could work efficiently to remove them and restore the house and neighborhood “back to where it was.”

But sometimes, when police try to yank people from other people’s homes, things don’t go as planned.

‘Something weird is happening here’

The two-story, 1950s-era house in northern Miami has exterior stains, a headless palm tree, a large, randomly placed wooden fence in the front yard, and an electrical cord running from a side window to the back of the property.

County records show a string of code violations in the past decade, and owner Valentina De Leon said she and her family moved out less than a year ago after the lights and water got shut off.

De Leon, who owns a hair salon and hails from the Dominican Republic, said through an interpreter that she stopped by every day and maintained the house. But then, neighbors called to say people were partying there.

She called police, who drove up April 18 to remove the squatters. After the two adults and the child came out, the police spent the next few hours largely milling about and on the phone with various officials, trying to figure out what to do.

Ultimately, the trio stayed. It was a civil issue, Garcia said: Not only was there an adverse possession filing, but the occupants also had paid the last two years’ worth of property taxes, officials confirmed to him.

The adverse possession claim was denied because the applicant used a business name, not a personal one, Garcia said. But if the owners wanted the people to leave, they’d have to evict them.

“Something weird is happening here,” Valentina said at the scene.

The rejected applicant, Bob Dolcine, filed another adverse possession claim for the house on April 19, the day after the aborted removal, but this time in his own name, county records show.

When the Review-Journal called the number listed on his applications, a man answered. But after the paper asked to speak about the house, there were several seconds of silence before he said, “Can I call you back?”

The Review-Journal didn’t hear from him again.

On the day the cops showed up, the man who came out holding the adverse possession paperwork declined to answer questions from the RJ, including what his name is.

“My name is whatever you want it to be,” he said.

Around 6:50 p.m., as the cops were getting in their cars to leave, he picked up a garbage bag out front and dropped it in a container.

He then walked into the house and closed the door, making himself right at home.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Follow @eli_segall on Twitter.

Related

Steps officials have taken to end squatting in Las Vegas, Miami areas

The house was for sale — but the sign suddenly went missing