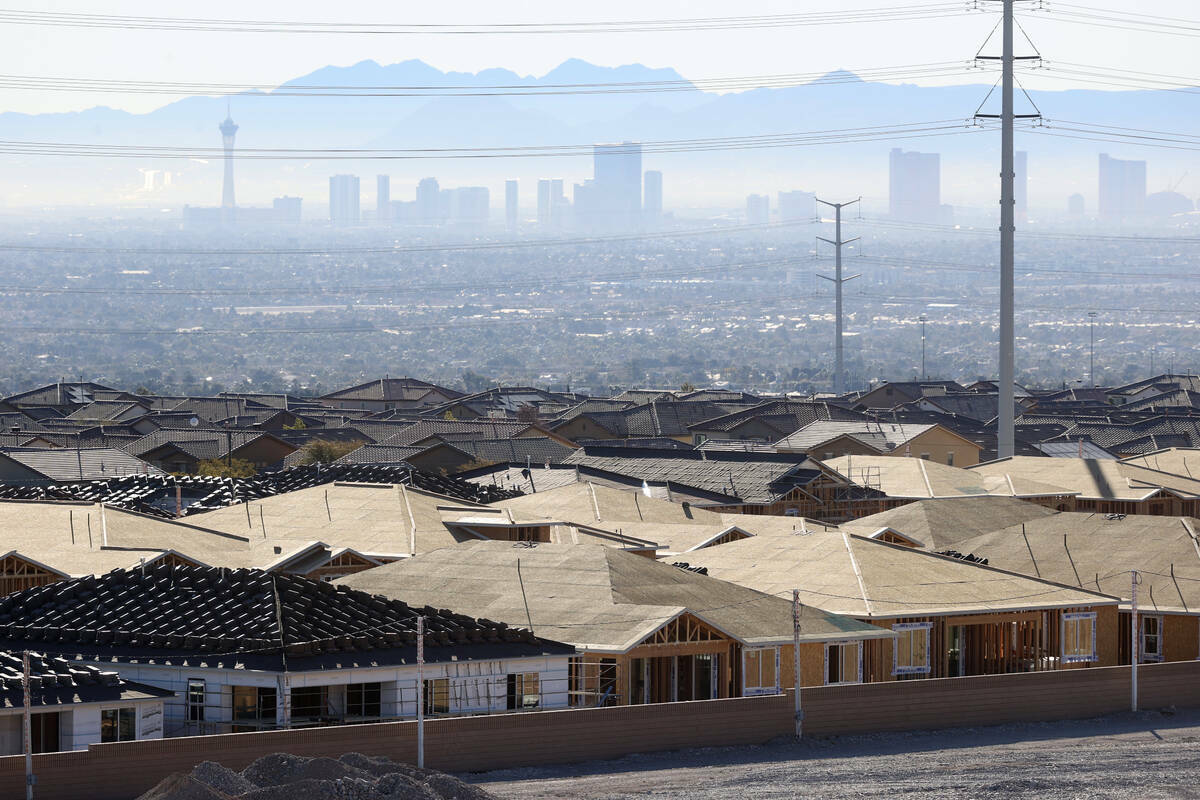

Welcome to Las Vegas’ housing crisis in 2024

There is no way around it, the Las Vegas Valley has a big problem, said the leader of the Nevada Housing Coalition.

“Straight answer is we have a housing crisis in every sense of the imagination,” said Maurice Page, executive director for the coalition.

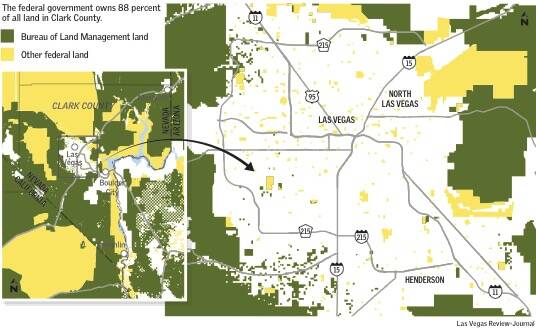

Nevada is short more than 78,000 affordable rental units for extremely low income renters, according to estimates from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Plus, the valley is landlocked with 88 percent of Clark County alone controlled by the federal government.

Steve Aichroth, administrator for the Nevada Housing Division, agrees the valley is in a housing crisis. He said the state department is working to incentivize the private sector to build more affordable units and has administered $1 billion in housing assistance since the pandemic, including rental assistance, homeowner assistance, eviction diversion and housing development.

The shortage of housing has hit the desks of various politicians and looks to be a prime issue in the November election. Sen. Jacky Rosen, D-Nevada, sent a letter dated June 13 to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development expressing her concern over the impact corporate investors are having on the housing market.

“At a time when hardworking Nevada families are facing high prices and low supply when looking for a place to call home, predatory practices by corporate landlords exacerbate existing barriers,” the letter states.

A Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation, done in conjunction with research data from Shawn McCoy, director of the Lied Center for Real Estate and an associate professor at UNLV, found investors could own more than 15 percent of all of the valley’s residential housing stock.

Several stakeholders, analysts and government officials who spoke to the Las Vegas Review-Journal all agreed the valley is in a “housing crisis” and serious action needs to be taken. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, someone making minimum wage in the state of Nevada would have to work 82 hours a week, essentially double a regular working week to be able to afford a one-bedroom apartment at fair market rate.

Purchasing power of California residents

Page said one of the biggest problems is Nevada’s proximity to the mighty purchasing power of California residents who have been inflating the valley’s real estate prices and squeezing renters for decades.

The median sale price for a Los Angeles home, according to Redfin, is $1.05 million. The average wage in the state is $73,220, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The median sale price for a home in the valley is $440,000 and the average wage is $55,490, Redfin said.

“In my estimation we needed to start looking at this issue as far back as 2011 or 2012 after the recession, because what we saw were individuals and investors starting to come to Nevada to buy up homes,” Page said.

Page said the pandemic put the local housing crisis into overdrive as remote workers flooded into the valley, and now the shortage of real estate and affordable homes and rentals are pinching all aspects of residential real estate.

Clark County has also thrown hundreds of millions of dollars at the problem through various funds including its Welcome Home Program and Community Housing Fund. But Aichroth did concede that is seems simply trying to spend our way out of the problem isn’t necessarily working.

“So yes, government is part of the problem, but is government part of the solution? Yes. We occupy that space, we like to think that we are on the solution side of creating the opportunities to provide these homes, and I think we are in a different place than where we were heading into the Great Recession,” he said. “There was a lot of freewheeling and so the government clamped down and that’s to prevent something like that happening a second or third time, so there needs to be regulation in the private market to do this.”

Government in the way?

The Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act, which was passed in 1998, has come under increased scrutiny as of late as many say hundreds of thousands of acres within the valley are prime for development but are not being put up for auction by the Bureau of Land Management in a timely manner.

Theresa Coleman, the district manager for the Southern Nevada District Office, said in an email response to the Review-Journal that the BLM works closely with local governments and that parcels that are made available are determined through a joint selection process.

The interested party must ask the local government where the land is located to approve the land being sold. If the local jurisdiction agrees, it submits a nomination to sell the land to the BLM. BLM then moves the land to be sold at an upcoming auction.

Approximately 27,000 acres (which is approximately the size of Summerlin) remains available for “disposal” by the BLM.

Bob Cleveland, chief executive officer for Rebuilding Together Southern Nevada, which helps low income people with home repairs, said unlocking land for development is a good step, but it’s more complicated that the government simply getting out of the way of the private sector and letting capitalism take its course. In fact, he said that could make things worse given the current market and overall economy means price points are incredibly high for developers.

“Long term, yes, short term I don’t think it matters,” he said when asked if the government releasing more land for residential development will help the valley’s housing crisis.

“There is a lot of land that has already been released. The housing crisis comes because there is no affordable housing and you talk about people coming here from California, they’re selling their three bedroom house for a million bucks, and coming here and buying a 2,500-square-foot house for $600,000 and it’s just driving the prices up and that is going to continue and there’s nothing we can do about that. Just because you release BLM land that just gives developers more room to build and they’re not going to build affordable housing.”

Contact Patrick Blennerhassett at pblennerhassett@reviewjournal.com.