Federal report outlines reforms to Las Vegas police

Las Vegas police training is scattershot and inconsistent. Policies are cumbersome. Poor radio communication and other tactical errors often happen during officer-involved shootings, according to a wide-ranging U.S. Department of Justice study of the agency released Thursday.

The study lays out 75 findings and recommendations for the agency, covering issues from a lack of "fair and impartial policing training" to reforming a "police-friendly" Use of Force Review Board.

"I strongly feel this report can help the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department," said Bernard Melekian, director of the Justice Department's Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, or COPS. "The potential here is great."

Officials said the goal is to change the culture of a department that is open to change but has for years lacked even basic measures of accountability for officers' actions in a shooting.

"That's the main reason for the recommendations - the lack of accountability that's gone on," said James K. "Chips" Stewart, a former Oakland, Calif., police chief who headed the study.

The Justice Department also addresses other organizations beyond the Metropolitan Police Department. They recommend that Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson take a more active role investigating police shootings, not just fatal ones. And police unions were advised to encourage their members to cooperate with investigators after shootings.

The 154-page study is an extensive, sometimes bluntly critical look at a department that has faced increased scrutiny in the wake of controversial incidents and a yearlong investigation of officer-involved shootings by the Las Vegas Review-Journal. The agency shot and killed a record 12 people last year and tied its record of 25 total shootings in 2010.

The number has dropped significantly this year.

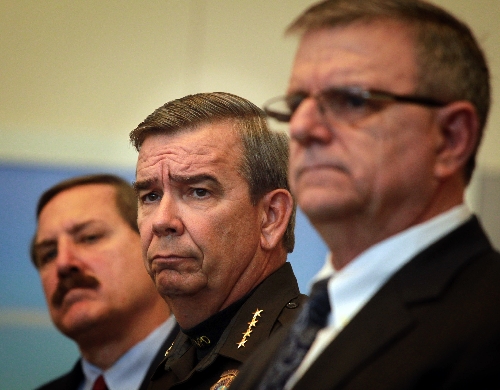

Sheriff Doug Gillespie pledged to implement the Justice Department's suggestions. His department has completed many of them already, he said.

"We will not be judged today based on this report," he said. "We will be judged based on how we follow through on the recommendations in the months to come."

U.S. OFFICIALS TO FOLLOW UP IN SIX MONTHS

Federal officials praised Gillespie and his department for transparency and cooperation with investigators, but the officials said they plan to check on the department's progress within six months and issue a follow-up report in a year.

Melekian said the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division could still sue the department and seek a binding consent decree that would force changes. That decision could depend on how the agency reacts to the COPS program recommendations.

Stewart said they've given the department a path to success.

"It can build community trust, enhance accountability in use of force and reduce the number of preventable officer-involved shootings, while enhancing officer safety," he said.

If the study results in fewer shootings, federal officials believe it will be a model for future federal intervention into police departments - a collaborative process instead of the contentious and more costly Civil Rights probe.

The study wasn't enough to satisfy the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada and the Las Vegas chapter of the NAACP, which both filed a petition a year ago seeking an investigation by the Civil Rights Division, which can be far more controversial than the COPS approach.

"We want more reforms than what are in this report," ACLU of Nevada Executive Director Dane Claussen said.

They were critical that the study doesn't require Las Vegas police to adopt the changes, that the study's authors didn't seem to support the coroner's inquest process and that they didn't advocate equipping officers with body cameras.

The scope of the Justice Department's investigation started in 2007, when the "accountability mechanisms LVMPD had in place to impartially and thoroughly review OISs were extremely limited," the report said.

Since then, things have improved. But not enough.

Las Vegas police already have adopted many of the Justice Department's policies. But changing policies alone doesn't accomplish the end goal: changing department culture.

The study's authors interviewed officers in a variety of roles throughout the department and sat in on several training sessions. They came away with honest answers from cops and troubling impressions that reveal how hard it can be to change the culture of a major police department.

Instructors who were to teach a new use of force policy this year undercut the changes, the authors noted.

"Most troubling is the fact that, on some occasions, LVMPD instructors expressed outright disapproval of some components of the new policy to trainees during class," the report said.

When it came to regular training for hand-to-hand combat and Taser use, the sessions were inconsistent, ranging in length from just 30 minutes to four hours.

Pressure to "keep cops out on the street" and "get training done and out of the way" was common, the report said.

The department also doesn't provide specialized training aimed at eliminating ethnic bias. The report notes that in the 10 shootings of unarmed people during the study period, seven were black.

"The span of an officer's career is mostly void of such training," the study said.

Other voids include:

■ Some officers complained that they aren't getting enough training on de-escalation techniques, a progressive approach the department rolled out earlier this year that focuses on ways officers can avoid turning non-violent encounters with citizens into violent ones.

■ While some officers are trained in crisis intervention, designed to recognize people with mental illnesses or other disabilities, many haven't been recertified in as long as nine years.

■ Some detectives assigned to investigate officer-involved shootings get no training on how to do so.

Proper - and useful - training is critical to keeping officers and the public safe, and the Justice Department's team has ideas for remedying the department's deficiencies. They include requiring more, and better, training in reality-based scenarios, and audits of training sessions.

Gillespie said he wasn't surprised by many of the study's findings, but he was particularly bothered that instructors weren't properly following through with policy changes.

"That concerns me, and that's an aspect of the report that I'll pay particular attention to," he said.

POLICE POLICIES DRAW SCRUTINY

In its investigation, the Review-Journal found that the department is slow to recognize patterns in shootings, or missed them entirely. The department didn't change policies in ways that would reduce shootings and didn't hold officers accountable for policy violations in a shooting, the newspaper found.

The Justice Department reached the same conclusion.

"They were not in keeping with best practices," Melekian, a former chief of police in Pasadena, Calif., said of the agency. "They were outdated and, quite honestly, not meeting the community's needs."

Even the department's new use-of-force policy is "cumbersome and not structured in a clear and concise manner that allows officers to quickly apply guidance in the field."

The COPS office and CNA, the Virginia-based nonprofit hired to do the study, used data provided by the newspaper to analyze five years of shootings. They found that shootings of unarmed people were more likely when an officer initiates an encounter, such as stopping someone for jaywalking, and they encouraged more training on when such stops are legal.

Tactical errors, including breakdowns in radio communication, occurred in at least 40 percent of shootings. Those problems included failure to update dispatchers, using the wrong radio channel and not communicating with officers en route to the scene. The department recently announced that it will scrap its new radio system because of technical problems. Two of the 35 communication breakdowns involved radio malfunctions.

The Justice Department recommends that officers use radios in training scenarios, something they rarely do now.

The study also noted weaknesses in the agency's street-level supervisors. They found that tactical errors and fatalities were more prevalent when multiple officers were on the scene.

That has been the case in some of the department's most controversial shootings in recent years, including last year's killing of disabled Gulf War veteran Stanley Gibson. Even with supervisors on the scene, one of several officers fired his AR-15 rifle seven times into the unarmed man's car. Exactly what happened has not been made public, and the case is under grand jury review.

Researchers also observed six reviews of shootings by the department's Use of Force Review Board, a panel of citizens and officers who determine whether an officer's actions violated department policy.

The Review-Journal's investigation showed that the panel was inherently skewed in favor of the officer, and it cleared officers 99 percent of the time over a 10-year span.

The study's authors described the board as "police friendly." In each hearing, they noted, the department investigator presenting the case said nothing about the history of the officer under review, offering no information about prior disciplinary issues or shootings.

That was in stark contrast to the history of the person who was shot, or shot at, they observed. That person's history of encounters with police, drug use and other patterns of behavior were laid out for the board, the authors said.

Also, "Leading questions were posed to the involved officer in each (hearing) we observed," they wrote.

The Justice Department's recommendations include auditing hearings to ensure training is successful and a new method of finding citizens to serve on the board.

Audits and increased accountability were emphasized in the report. The public appearance of credibility is paramount, and some members of the community expressed frustration about "police leadership that tolerates lapses."

As one former police official confided to the Justice Department's team: "They are not consistently vocal enough in demanding accountability for officer excessive use of force violations."

DOJ PRAISED BY DISTRICT ATTORNEY

Wolfson had high praise for Justice Department's study.

"I think it's a new day for this community based on this report," he said.

He said he would consider the agency's recommendation that his office gain more training and develop expertise and investigate all "significant" use of force and issue detailed reports. He currently does that for fatal encounters with officers, which was a significant departure from past practice.

The Justice Department also addressed the controversial county coroner's inquest process, questioning its role now that prosecutors make public their reviews of fatal police shootings. They recommend the County Commission, which overhauled the process just last year, revisit the subject. It is expected to do so next month.

Wolfson said he would like to see some public process in addition to release of his office's decision letters.

Gillespie, who saw the report for the first time Thursday, said that he didn't see anything objectionable in the study and that he expects his officers will able to implement all of the recommendations.

"I've always said, there's room for improvement," Gillespie said. "Nobody likes to be told you're not meeting the mark. We'll get past that, and we'll focus on the parts of the report that will help us."

Contact reporter Lawrence Mower at lmower@reviewjournal.com or 702-405-9781.

U.S. Department of Justice report on officer-involved shootings by Las Vegas policeDeadly Force: When Las Vegas Police Shoot, and KillLas Vegas Review-Journal investigative series