7-year-old girl’s murder at Nevada casino still haunts 20 years later

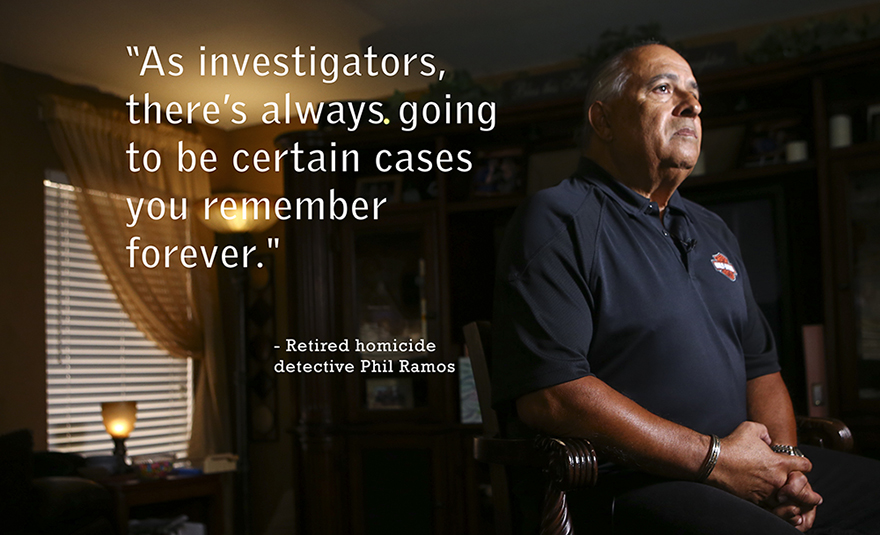

Phil Ramos still sees her smiling face, forever frozen in a photograph.

Her name is Sherrice Iverson, and she was 7 when she was lured from an arcade into a Primm casino restroom 20 years ago, forced into the largest stall, sexually assaulted and slowly strangled before her killer snapped her neck.

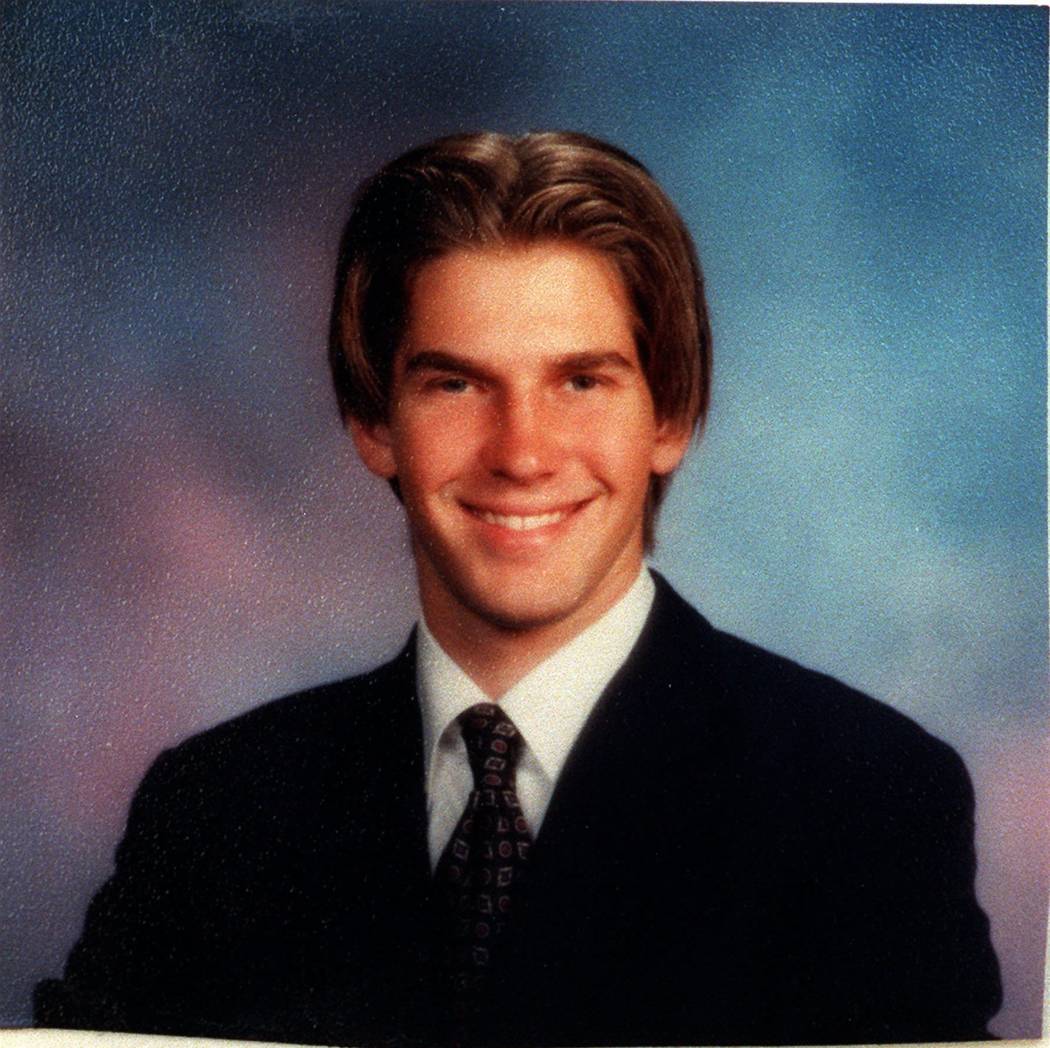

A copy of that portrait — her smile wide and earnest — now sits in a cardboard box marked as “evidence” at the Regional Justice Center in downtown Las Vegas. The man convicted of her murder, Jeremy Strohmeyer, sits at High Desert State Prison in Indian Springs.

The shocking case started a national conversation on casino security and whether gaming properties should be required to provide child care. Its fallout also led to a new good Samaritan law aimed at protecting child victims of crime.

Ramos, now retired, was one of its lead homicide detectives.

“As investigators, there’s always going to be certain cases you remember forever,” Ramos said this month in his northwest Las Vegas home. “The Sherrice Iverson case is definitely one of those, just because of the dynamics of it: the absolute sheer innocence of the victim, the brutality of how she was killed, and the nonchalant attitude of Jeremy Strohmeyer.”

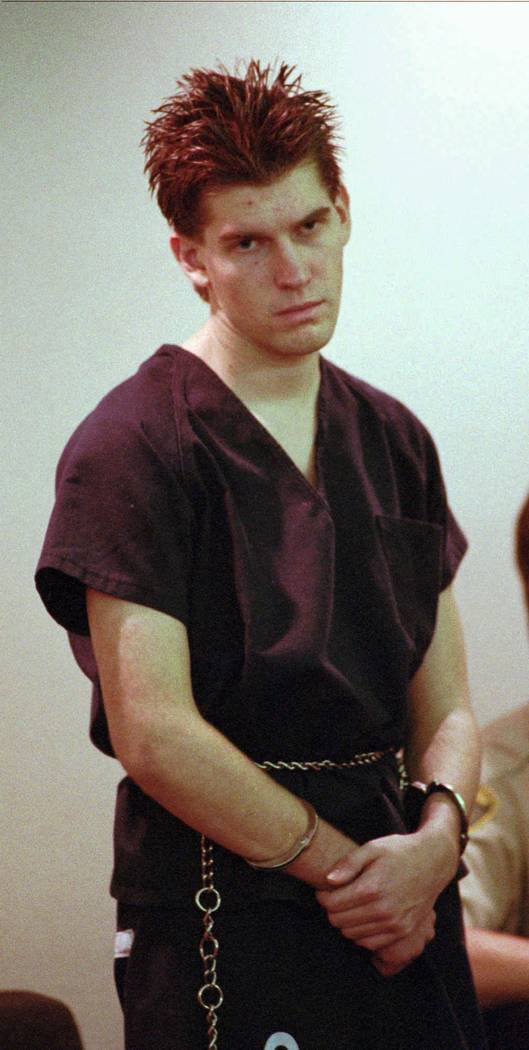

Strohmeyer, now 38, is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for murder, kidnapping and sexual assault. At the time of the slaying, he was a high school senior, adopted at birth by a well-off Long Beach family, Ramos said. He pleaded guilty to his charges in 1998, and in exchange, prosecutors agreed not to seek the death penalty.

In 2000, Strohmeyer appealed, arguing that his lawyers pressured him to make the deal. In 2006, a federal judge upheld the conviction.

Strohmeyer continues to fight for the possibility of parole. A hearing on the matter is scheduled for June 12.

“Every time I drive to Southern California by state line, I look over there, where the resort is, and replay it,” Ramos told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “Whenever I’m in Southern California, in Long Beach, I think of it. Whenever I hear about a kid being killed, I think of it.”

Collateral damage

Sherrice was found about 5 a.m., after her father desperately searched for her, screaming her name. To this day, the hotel staff retains a collective sense of guilt.

“They felt bad about forcing her off the casino floor, because then she became vulnerable,” former Primm Valley Resort medic Bart Stinson said. Nevada law prohibits children from lingering in casinos.

Stinson, now 62, had just commuted from Las Vegas the morning of May 25, 1997. To clock in about 6:30 a.m., he had to pass the downstairs arcade, where he noticed bright yellow crime scene tape blocking the nearby women’s restroom. An officer was standing guard.

“I thought it was a crazy girlfriend or boyfriend,” Stinson said. It wasn’t until he walked upstairs into the EMT briefing room, exactly one floor above where Sherrice was killed, that he learned of the horror that had happened just a few hours prior.

“I was taken aback,” he told the Review-Journal this month. “In the middle of the night at a casino, you don’t think it would be a 7-year-old girl.”

Though Stinson didn’t respond to the scene, he said his co-worker, a young man, did.

“He was a chain smoker. Tough kid. But it screwed him up,” Stinson said. “He was in therapy for the rest of the time I knew him.”

Stinson said the housekeeper who found Sherrice — and then guided Sherrice’s father into the restroom stall to see her — was deeply affected, too.

“She would have panic attacks. The rest of the time I worked there, I would get calls for her,” he said. They would happen randomly, as she was cleaning a room, or walking the casino floor. “She was in real bad shape.”

The murder happened shortly after 3:48 a.m., when Sherrice was last seen on surveillance footage, walking into the restroom. Her 14-year-old brother was somewhere else in the casino, and her father, Leroy Iverson, was upstairs playing slot machines.

Iverson didn’t have money for a room. The plan was to stay and gamble for several hours while his kids played in the arcade. He told police he had done it several times in the past.

“She was like any 7-year-old, running around, screeching. And they’re not supposed to be on the casino floor,” Stinson said. So more than once that fateful night, casino employees reunited a wandering Sherrice with her father, and told him he needed to attend to her.

More than once, she ended up back in the arcade, where Strohmeyer found Sherrice while perusing the property with his friend, David Cash Jr. Cash watched as Strohmeyer forced Sherrice into that stall. He even leaned over the stall and tapped on Strohmeyer’s head, but he never intervened, never reported the crime and never faced criminal charges.

Innocent child

Sherrice would be 27 now.

She was a smart Los Angeles second-grader who loved learning and had dreams of becoming either a nurse, police officer or dancer, her mother, Yolanda Manuel, told Strohmeyer in court the day of his 1998 sentencing.

“Are you a demon? Are you a devil?” she asked Strohmeyer, raising her voice before apologizing to the judge for her demeanor. “You are so evil if I had a wish here I would put you to death the same way you put my child to death. If it was my prison, I would blindfold you and shoot you in your feet and send you back to your cell.”

Efforts to find Manuel for this story were unsuccessful. Her California lawyer, Steve Lerman, who also represented Rodney King, told the Review-Journal that Sherrice’s death “ruined her life.”

Sherrice’s father died in 2000. Efforts to reach Harold Lee Iverson, her brother, now 34, were unsuccessful.

“Sherrice was just as innocent a child as you could think of. This poor little thing did absolutely nothing,” Ramos, the detective, told the Review-Journal. “She was just being a kid, just playing in the arcade.”

Ramos said Strohmeyer “targeted her from the minute he got down there to that arcade.”

“He was like a lion on the Serengeti, chasing down his victim.”

On a scratchy cassette tape of Strohmeyer’s confession, recorded four days after the killing, the honor-roll student can be heard matter-of-factly describing the act.

Ramos can be heard on the tape, too, asking Strohmeyer if Sherrice’s eyes were open or closed before he left the stall. The detective was searching for some glimmer of remorse.

“I don’t, I don’t think I really looked at her eyes,” Strohmeyer said. “I don’t recall really looking at her face at all.”

Plea for forgiveness

Strohmeyer is married now, to a woman he met through letters about 14 years ago. They were wed in the visiting room of Lovelock Correctional Center in 2009.

“The label ‘prison wife’ may warrant some negative attention because a lot of people are ignorant to the fact that not all of us women who stand by our incarcerated men are desperate, or delusional,” his wife, Desiree, wrote in a blog last year, a day before their seventh anniversary. “We love. Plain and simple. I’m a normal woman. I like wine, I have a cat, I drive a Toyota, I work and am a functioning part of society.”

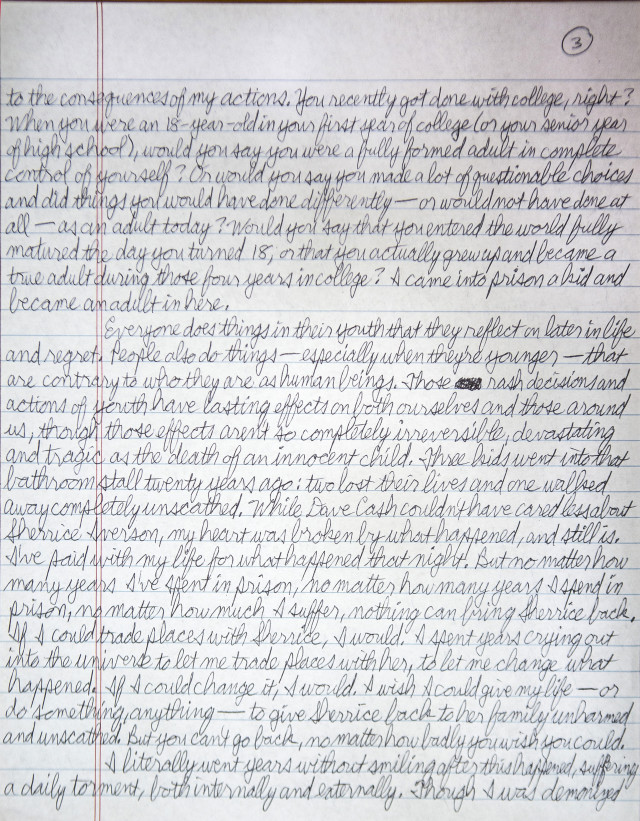

In a handwritten letter to the Review-Journal this month, after he was asked about the case, Strohmeyer said he wants Sherrice’s family to know he is sorry.

“I want to ask for their forgiveness, and I want them to know I would give anything to trade places with Sherrice,” Strohmeyer wrote. “I just want them to know I am sorry, more sorry than words can ever say. I wish nothing but peace and good lives for them wherein their lives are not defined by this horrible tragedy as mine has been.”

In the letter, Strohmeyer said he has committed to improving himself and the world around him. He said he works with young prisoners, trying to get them to be “less impulsive, to think about their actions.”

“Prison is an angry, hateful, paranoid place most of the time, where everyone is your enemy,” he wrote. “I try to defuse that blind malevolence in the hopes of making life more bearable for those around me, as well as in the hopes of evincing the goodness inside each of these guys so they’ll go back into the world with hopeful and helpful hearts instead of hearts filled with anger and bitterness.”

He does so, according to the letter, because he owes that “to Sherrice, her family, and society.”

Ramos doesn’t buy it. When read some of Strohmeyer’s comments, the detective paused for a few moments.

“I don’t know what to make of that,” he said. “I don’t have any kind of sympathy for him in any way, shape or form. He was a vile person who committed an unspeakable act. There’s no way any remorse he thinks he feels right now is going to change any feelings that I had for him at the time that he did this, or even today.”

“I know that eventually he will die in prison,” Ramos continued. “And that’s about the only salvation anyone, myself included, can receive after what he did.”

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter.

RELATED

In Strohmeyer case, 'bad Samaritan' David Cash led to new law

Resorts official says industry improved vigilance in keeping children off casino floors