Meet the man whose ‘crazy idea’ jump-started Nevada’s COVID Trace app

Entrepreneur Andrew Pascal built a company that builds apps.

So when the Las Vegas resident considered what he could do to help Nevada during the pandemic and learned of the challenges inherent to contact tracing, the answer seemed clear enough.

His company would develop a contact-tracing app. Or so he thought.

Pascal, 54, did become a driving force in bringing to the state the COVID Trace app that launched on Monday. But not in the way he first envisioned.

Early in the pandemic, Southern Nevada Health District investigators were calling each person who tested positive for the coronavirus to request the names of close contacts who might have become infected. The investigators would in turn advise these contacts to self-quarantine to curb the spread of COVID-19. But as cases mounted, investigators were quickly overwhelmed, and backlogs piled up.

“Are you kidding me?” Pascal said in an interview this past week, describing his reaction to what he initially learned about the mechanics of contact tracing. “In the face of the pandemic, where you have this rapid transmission of a virus, you gotta talk to everybody and try to somehow construct the network of people that they’ve been exposed to?

“How could you possibly do that fast enough and inform people fast enough for it to really matter and make a difference?”

A ‘crazy’ idea

Early in April, Pascal announced to his wife and two daughters at breakfast that he wanted to create a contact-tracing app.

“Do you think this is kind of crazy? I think it’s a solid idea,” he told them.

“They’re supportive of each of my crazy ideas. That’s where it kind of started for me.”

Pascal is the founder, chairman and CEO of PLAYSTUDIOS, which develops casino games for mobile and social media platforms. He began to talk with his team about building an app, one that would preserve privacy and whose use would be strictly voluntary.

As Pascal researched this idea, he explored whether there might be a suitable app already in development. “But I really didn’t find anyone other than a specific group up in Washington state that seemed to have just been really focused on solving the problem elegantly, simply.”

The group in Seattle included Dudley Carr and his brother, Wes, software engineers who had been working since March to develop a contact tracing app that put privacy front and center.

“That’s kind of how we’re wired,” Dudley Carr said. “We really want to jump in to help solve problems.”

Google and Apple unite

In May, app development took a huge leap forward when rivals Apple and Google joined forces to offer technology for a notification system for contact tracing that would work on both iPhones and Androids. They stipulated that their technology could only be used in partnership with public health authorities.

Their technology allows mobile phones to anonymously exchange random IDs or “tokens” when users are within close proximity of one another, as determined by Bluetooth signals. To help ensure these random IDs can’t be used to identify a user or their location, they change every 10 to 20 minutes.

An algorithm calculates whether over the course of a day a user has cumulatively been the equivalent of 6 feet from an infected individual for at least 15 minutes, Carr said.

No personal information is captured during the exchange of tokens. The tokens are temporarily stored on the user’s phone.

Those who test positive for COVID-19 in Nevada are asked by health officials in Nevada if they are using the COVID Trace app. If so, they will be provided with a code they can enter into their phone. By entering the code, phones with which their device has exchanged tokens will receive notification if, based on the algorithm, there was possible exposure. They also will receive advice about what to do next.

Carr and his team used the Google/Apple technology as the basis for the app they were developing, one that would be geared toward the needs of Nevada.

But the technology was just one piece of bringing the app to the state.

“The technology is one aspect, but it’s important to engage businesses in the community and unions and so on,” Carr said. “The rollout is as important, if not more important, than the tech.

“And I think that’s really where Andrew was the driving force to actually get that all happening for Nevada.”

Evangelizing for the app

Early in the outbreak, Pascal had conversations with Jim Murren, chairman of the Nevada COVID-19 Response, Relief and Recovery Task Force, about helping the state’s effort.

Pascal, who a decade ago served as president and chief operating officer of Wynn Las Vegas, and Murren, who stepped down earlier this year as chairman and CEO of MGM Resorts International, have known one another for more than 25 years. Pascal described Murren as both a mentor and friend, and they also are neighbors in the The Ridges, an upscale neighborhood in the far west Las Vegas Valley.

“What I told Dudley was that I felt like Nevada was really in a unique situation, where you had a group chaired by Jim at the urging of the governor to go help find and solve these problems,” Pascal said. “And so we would have a receptive audience not only with Jim and the task force, but also the opportunity to really educate the governor’s office and all the appropriate health agencies within the state about the solution.”

He said he and Murren began to “evangelize” for the app to get buy-in from state health officials, government leaders and businesses. There was some hesitancy, particularly around issues of privacy.

But Pascal said the design of the app carried the day.

“There’s nothing about the Bluetooth tokens that are being exchanged that could in any way be used to compromise someone’s identity or violate the trust and the kind of social contract that the user has with the state providing the service,” he said.

Carr said privacy was top of mind as his team worked on the app, in part because he thinks in general too much data is gathered through technology.

“If not done right, people would not use these apps if they weren’t inherently private,” Carr said.

He described the app as the “gold standard” for how private yet effective an app could be. He is frequently asked how private the app is, but he said the better question is: “Why aren’t more apps this private?”

App obstacles

The trade-offs for such privacy have become a chief criticism of apps based on the Google-Apple platform. Critics have said they don’t provide users with enough information, such as where possible exposure took place, to effectively evaluate their own risk.

Another issue is that the handful of states launching apps are doing so independent of one another, with systems that aren’t interconnected. This means that if a tourist with the Nevada app tests positive in his home state, the devices with which his phone has exchanged tokens won’t necessarily be notified. That is because health officials in most other states aren’t yet coordinating with Nevada to provide the codes for users to input that trigger notification.

But the tourists themselves would be notified of possible exposures to people testing positive in Nevada.

Julia Peek, a deputy administrator for the Department of Health and Human Services, said Nevada officials have begun to contact nearby states about the app to improve coordination. She has described the app as complementary to Nevada’s other contact tracing efforts.

One potential issue could have been paying for the app, but Pascal again stepped in. Through his company, he is underwriting the cost. He declined to provide a dollar figure.

Instead of becoming a builder of the app, “I’ve been more of a kind of an evangelist, and I’ve also helped to underwrite the effort. That was another big part of this, just to remove any potential obstacles,” which meant telling the state, “Look, we’ll pay for everything,” he said.

“We’re delivering a solution that can just be supported and embraced by the state for the benefit of everybody that lives here.”

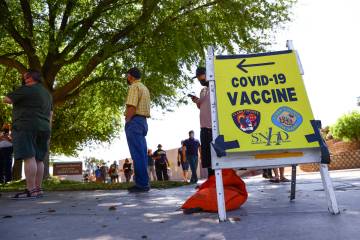

As of Friday, the app had been downloaded nearly 16,000 times.

More information on COVID Trace can be found at the state’s nvhealthresponse.nv.gov website. Those with questions about downloading the app may contact help@covidtrace.com.

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.