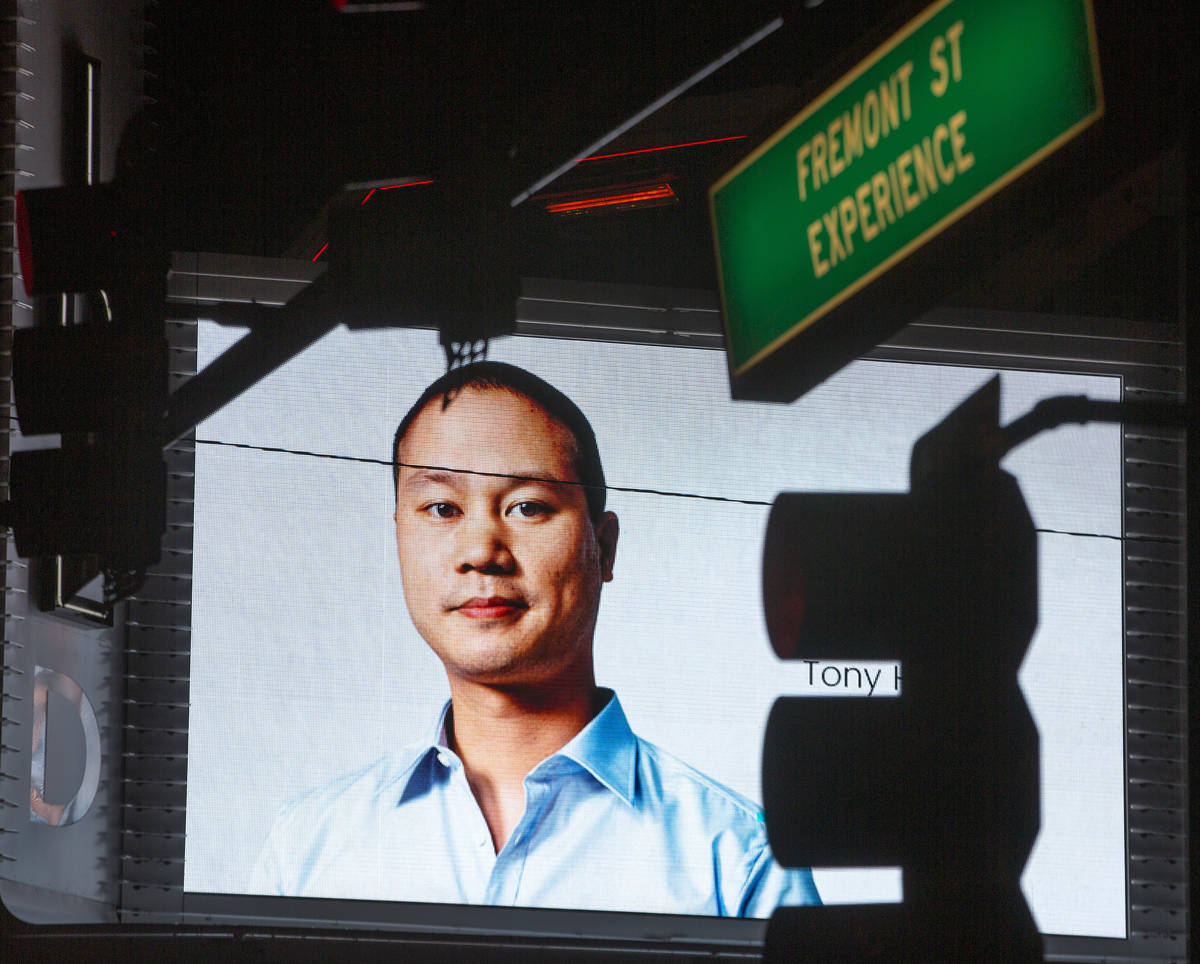

No doubt Tony Hsieh impacted Las Vegas. Was his vision a success?

To former Las Vegas City Councilman Bob Coffin, tech entrepreneur Tony Hsieh was a bit like another man who had an outsized impact on the city half a century ago.

“He was like a little Howard Hughes,” Coffin said of Hsieh. “His impact was as important as Howard Hughes’ impact 50 years ago when the town was in a very deep recession. East Fremont? It looked like a depression hit, and Tony brought it back and brought new people to invest.”

In 2012, the former Zappos CEO launched a side venture that put $350 million toward the revitalization of downtown Las Vegas. Hsieh wanted to transform the area into a connected community, a true hub for creative entrepreneurs to grow and share their ideas.

Over the years the Downtown Project, later renamed DTP, crystallized from a vision to downtown’s reality. The project drew its fair share of critics, but nevertheless helped transform downtown Las Vegas into a destination.

According to a 2017 Applied Analysis report, DTP has 407 ongoing or completed construction projects, has brought nearly $210 million in economic output, and helped create more than 1,500 jobs, resulting in roughly $70 million in salaries.

DTP has 61 small business investments within Las Vegas, according to the report, and owns roughly 45 acres of land in and around Fremont East and East Village Districts stretching from Las Vegas Boulevard to 14th Street. Much of that land has yet to be developed.

“In some ways it is like anything is better than empty parking lots,” Hsieh told the Review-Journal in March 2012, during the venture’s infancy. “The thing about a city is, even outside of Vegas, I don’t think there is ever a point where people say, ‘OK. This city is done.’ There is always something, a way for the city to evolve or be improved. I guess it is kind of analogous to the whole happiness thing. It isn’t trying to achieve some end goal; it is about ongoing progress.”

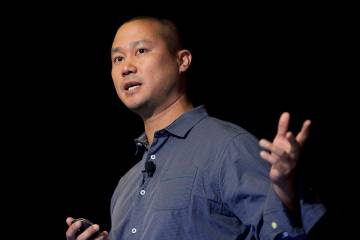

Hsieh’s vision

Michael Cornthwaite, owner of the Downtown Cocktail Room and formerly a close friend, said Hsieh first began discussing downtown’s future with him in 2009. At that time, Las Vegas was on the heels of the Great Recession and facing a long path to recovery.

“I think he was exactly who downtown needed at the time,” Cornthwaite said. “Times were tough, there were just a few of us in the area, and all were struggling to stay open in the economic crisis.

“He was ambitious in his goals. And, perhaps — looking back — they weren’t realistic in scale. But to anyone that was around in the beginning, what he did for downtown was nothing short of a miracle,” Cornthwaite continued. “It was a solid six years of magic.”

Hsieh’s vision attracted a number of people in the startup scene, including Frank Gruber, former CEO of Tech.Co, who moved to Las Vegas in 2012.

“He showed us the plans for what he was trying to do and the blank slate of downtown, which at the time was pretty dire in 2012,” Gruber said. “We saw the vision and believed that it could be done.”

Gruber’s company later became one of many to receive funding from DTP, a total of $2.5 million.

Tech.Co also was one of DTP’s success stories; after growing within downtown Las Vegas, the company was acquired by U.K.-based Global Digital Media Business in 2018.

But not all companies with DTP funding found success.

Critics arise

In 2014, the project stumbled.

Money got tight. Some of the startups DTP invested in shut down operations. Three prominent entrepreneurs involved with the venture died by suicide. DTP laid off 30 employees that year — approximately 10 percent of its workforce.

A number of onlookers who had long praised Hsieh and DTP began to critique the project.

In an open letter to Hsieh, former DTP employee David Gould wrote “‘Business is business’ will be the defense from those you have charged with delivering the sad news. But we have not experienced a string of tough breaks or bad luck. Rather, this is a collage of decadence, greed, and missing leadership.”

Gould told the Review-Journal later that day, Sept. 30, 2014, he still cared about the project and the people involved, and that Hsieh’s vision was “a correct one; it was an inspiring one.” Yet, his attraction to the project’s ideals soured as poor management and people interested only in money derailed its original mission.

“There were individuals I believe kind of squandered that,” he said. “It’s like they left the water faucet on all night. They didn’t understand that even though we had $350 million, it was still a finite amount.”

Aimee Groth, author of the 2017 book, “The Kingdom of Happiness: Inside Tony Hsieh’s Zapponian Utopia,” said DTP’s strategy was to place bets on a number of ventures. After a couple of years, certain startups began to run out of funding and were unable to secure a second round of investments.

“I think the world was tough on (Hsieh) during 2014,” Groth said. “People were hard on him in part because he cast this really grandiose vision, so he allowed himself to be measured against this really high standard.”

Groth said Hsieh’s plans for downtown were constantly changing — at one point, he wanted Las Vegas to be the shipping container capital of the world. Later on, plans shifted to making the city the co-working capital of the world.

Zach Ware, Hsieh’s friend and business partner, said much of Hsieh’s original vision to create the most connected large city in the world is “thriving.”

“When we originally formed Downtown Project, our goal was to help accomplish in five years what it takes most cities decades to accomplish,” he said. “Tony was proud of the catalyzing effect Downtown Project and Zappos had on increasing the energy and connectedness of the downtown community even though, as he had said, we made lots of mistakes as we learned.”

While Hsieh’s DTP brought in venture capitalists and entrepreneurs to Las Vegas, the city was never able to measure up to larger tech hubs like Silicon Valley. But those involved with the project, like Gruber, said that was never its intention.

“(Becoming Silicon Valley), that’s a big endeavor that took 50 or more years,” he said. “DTP validated Vegas as a place for starting up and fueled a lot of excitement. Startups moved here, moved to Vegas, and became part of that movement. It was bringing people together.”

Gruber said DTP’s vision is still a work in progress, but emphasized the restructuring of an area like downtown Las Vegas takes time.

“It’s not done yet, unfortunately,” Gruber said. “You can’t build a church for Easter Sunday. You have to build it incrementally.”

Downtown housing

Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries, roundly praised Hsieh for investing hundreds of millions into an area people used to avoid and transforming it into a food and entertainment destination.

“Some of (his investments) worked, some of them did not,” but he ultimately chose to spend $350 million on downtown when he could’ve spent it elsewhere, White said.

While White had only praise for Hsieh, others didn’t fully buy what the man who sold happiness had to offer.

Critics pointed to DTP’s lack of investment in downtown housing over the years.

Hsieh told the Review-Journal in December 2012 that he didn’t see housing as a priority for the project, noting the venture was nearly done buying up real estate.

“We are not focused on residential and for the most part are leaving that to other developers,” Hsieh said. “Instead, we are focused on office space for entrepreneurs, retail, small businesses, and in general helping make Fremont East a place of entrepreneurial energy and a safe, walkable neighborhood.”

By March 2013, the project frustrated some longtime downtown business owners by pricing them out of their leases through the development of East Fremont. One such casualty was the Fremont Family Market & Deli, at the time the lone grocer in downtown. Co-owner Steve Yono told the Review-Journal his landlord sold the building to DTP.

“Business owners say they understand the need for redevelopment, but add that they were never approached by the city or developers about what they’d like to see happen,” the Review-Journal reported.

Housing eventually came. The first DTP-funded housing would open in April 2015 with the 211 Apartments at 211 N. Eighth St. The complex opened with 315 units and rents ranging from $650 to $850, utilities and internet included.

DTP later partnered with Arizona developer The Wolff Co. to build Fremont9, a 232-unit rental complex at 901 Fremont St. that opened in 2018.

Next steps for DTP

In 2014, the Review-Journal reported that Hsieh’s role in DTP was largely hands-off. He bankrolled the $350 million initiative, but said at the time that he was “not the decision-maker” and was “not involved with any of the day-to-day details.”

DTP spokeswoman Megan Fazio said Hsieh had held a visionary role for the project. He employed other decision makers a few years after its inception to run the program, but was still involved in its “ultimate decision making and visions.”

With Hsieh gone, Fazio said the project plans to continue its mission, maintain operations of its properties under Gov. Steve Sisolak’s directives and “tell (Hsieh’s) story through the development of his assets.”

DTP owns seven plots of raw land that have yet to be developed, according to the 2017 report.

“Tony saw something no one else could and took the risk developing east of Las Vegas Boulevard,” she said via email. “I hope that in the years to come we can show his vision through the execution of what he wanted for Downtown. … Aside from us all losing a friend, mentor and visionary, the operations of DTP will continue.”

Contact Bailey Schulz at bschulz@reviewjournal.com. Follow @bailey_schulz on Twitter. Contact Mike Shoro at mshoro@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @mike_shoro on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Rio Lacanlale contributed to this report.