Widows of 2 officers insist their husbands’ COVID deaths occurred in line of duty

Officer Phil Closi, a 21-year veteran of the Metropolitan Police Department, was in his fourth year of a legal battle over medical retirement when he died of COVID-19.

“When the pandemic started, we knew it could be fatal for him,” said his widow, Jenn. “The kids stopped attending school in person and playing ice hockey. The pulmonologist said work from home, but Metro said that was not possible. The communications bureau refused to let him wear a mask on the phone, because his voice would be muffled for callers.”

At least seven employees died from the virus, but federal records show that Metro only considered two of them line-of-duty deaths. The department declined to comment on why officer Jason Swanger and Lt. Erik Lloyd were the only officers who received this distinction, but Jenn Closi and the widow of another officer said they blame Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo for omitting their spouses.

When an officer dies from COVID-19, according to Metro, the department reviews contact tracing and sends a recommendation to Lombardo regarding whether the death should be considered a line-of-duty death.

Lombardo, who is running for governor, wrote in a statement to the Las Vegas Review-Journal: “Anytime we lose an officer it is devastating for LVMPD, the families and for our community. We are grateful for their service, and they will never be forgotten.”

Phil Closi was diagnosed with industrial asthma in 2017 and had severe scarring in his lungs. Then 44, he had worked fire evacuations at Mount Charleston, had worked as a bike officer on the Las Vegas Strip and had directed traffic under the rocket fuel-filled air near Nellis Air Force Base during his career. His pulmonologist said all of those assignments resulted in 51 percent lung capacity by the time he was diagnosed and placed on light duty.

Metro reversed its policy on masks several times, but Jenn Closi claims her husband was still exposed to bug spray and cleaning chemicals against his doctor’s orders. The department did not respond to a request for comment regarding that claim.

The Closis traveled to Florida on July 16 because Phil Closi’s doctor advised him that humid air was better for his lungs. The day before they left, Phil Closi texted his wife: “I feel like I’ve been hit by a bus. I don’t feel well … It’s just my lungs acting up.”

Positive COVID test

He tested positive for COVID-19 within 10 days of his last shift, and doctors said it was “probable” that he contracted the virus at work, his widow said. Phil Closi died Aug. 11 at 48.

“I was told the night he passed away that our health insurance died with him,” Jenn Closi said through tears. “My whole family had COVID. Instead of consoling my kids, I spent 2½ hours fighting with the health trust. That’s a battle that didn’t need to happen, in my opinion.”

If Phil Closi’s death had been deemed a line-of-duty death, his family would have been covered under his health insurance, with no out-of-pocket costs, until his children were 26 and his wife was 65. Jenn Closi waited to hold her husband’s funeral while the department determined whether his death occurred in the line of duty. Ultimately, she scheduled the memorial for June.

Although he will receive a 21-gun salute, Closi’s casket will not be escorted by a police motorcade, police will not announce his “end of watch call” over the radio, planes will not fly overhead, bagpipes will not be played, and his name will not go up at Metro headquarters, Police Memorial Park or in Washington, D.C.

“If he had been able to retire, he would have lived,” Jenn Closi insisted.

Jenn Closi said Lombardo made the final determination that her husband did not die in the line of duty. She said Lombardo also had the power to let her husband medically retire but pushed the case into several appeals.

“It took 15 days for me to be contacted, on Aug. 26, with a voicemail from the sheriff offering his condolences,” she said. “He never formally told me anything, and I never received anything in writing about his status as line of duty.”

She said the final hearing regarding her husband’s claim for medical retirement took place while he was in the intensive care unit.

“My husband told anyone who would listen that they wanted him to die before it was over,” the widow said.

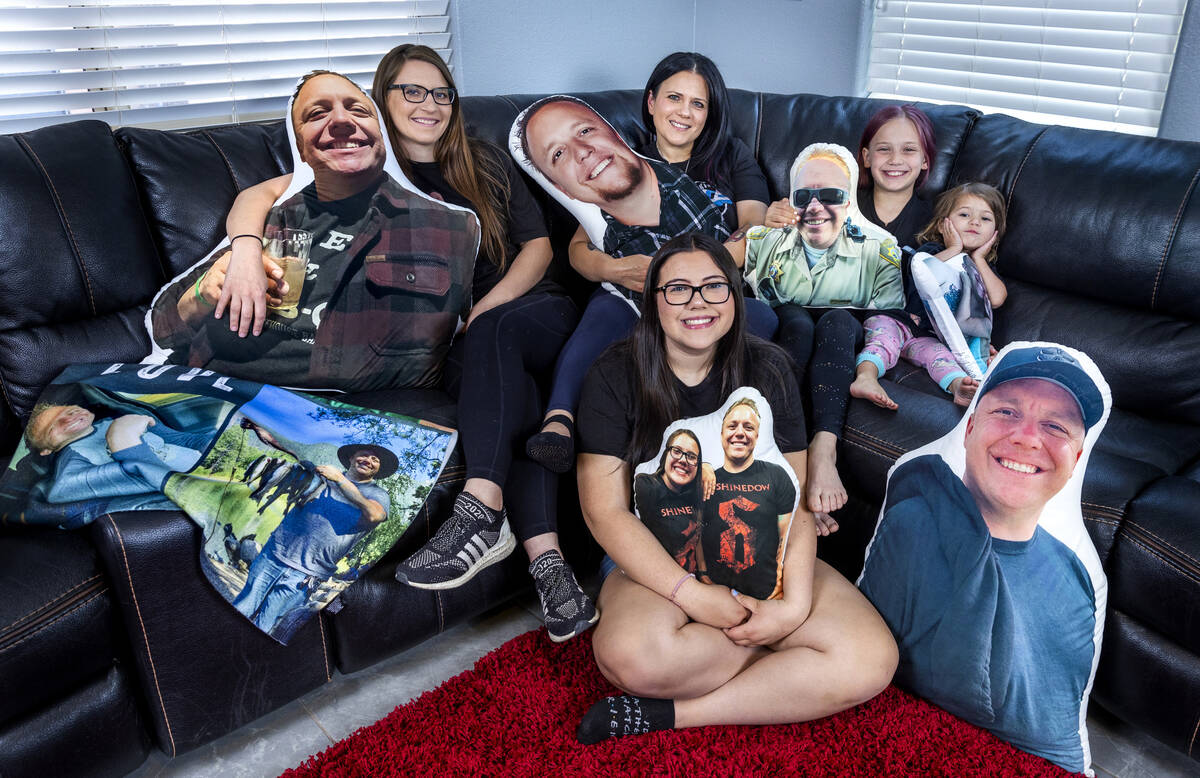

Now, Jenn Closi, her 17-year-old daughter and her 15-year-old son are left with just the stories of the officer who wanted to make a better city for Las Vegas’ youngest residents.

Phil Closi started a school violence awareness program at local high schools after a fatal shooting at Palo Verde High School in 2008. He worked in the D.A.R.E. program and volunteered with radKIDS, which taught children how to fight off abduction.

“He helped to humanize the badge for many children here in the valley,” Jenn Closi said.

Same month, another death

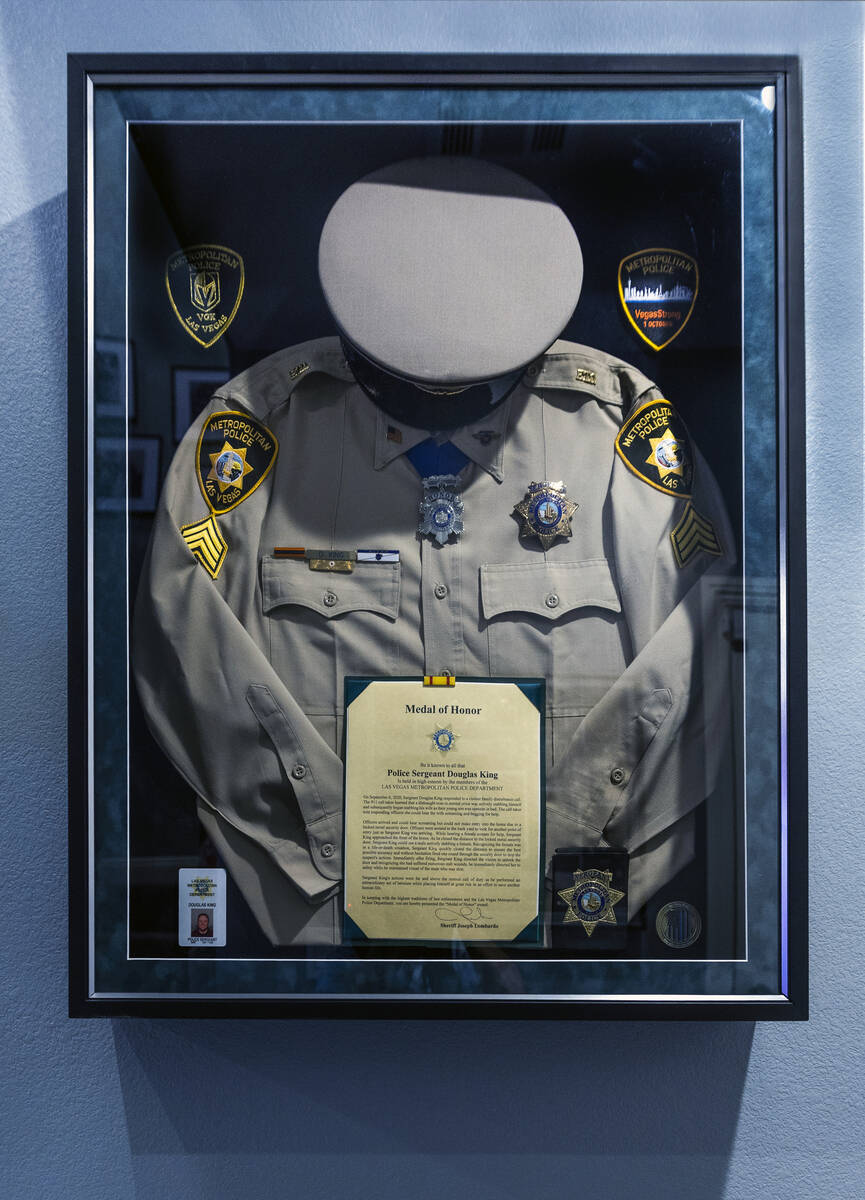

Less than two weeks after Phil Closi’s death, Sgt. Douglas King, 35, died of COVID-19 on Aug. 23. King was one of the first officers to arrive at the Route 91 Harvest festival shooting in October 2017, and later would receive the Medal of Honor posthumously for fatally shooting a man who stabbed his wife in Summerlin.

“My husband was a hero,” said Cinnamon King, who worked as a civilian employee in the communications bureau.

She recently retired from Metro after 15 years, so her benefits were not affected by her husband’s death. She and her husband worked opposite shifts and rarely saw each other, but she said Lombardo determined that it was not a line-of-duty death because he thought Douglas King caught the virus from his family.

“He had worked the whole two weeks prior to getting symptoms,” Cinnamon King said.

She said she learned that 16 other officers in the Summerlin Area Command were sick during that time frame.

“My daughter was only 8 when he died,” the widow said. “She had the world’s best dad. His picture deserves to be up on the wall at headquarters and the memorial wall in Washington. We deserve to be part of the memorial run at Police Memorial Park in his name. She deserves that. Her dad saved lives.”

Douglas King, a second-generation Metro officer, worked for the department for 17 years. His dad was a traffic officer for 25 years, and his uncle, Sgt. David Kinterknecht, was killed in the line of duty in 2009 in Colorado. The Montrose, Colorado, post office was renamed in his honor in 2019.

Cinnamon King said she and her husband had a daughter together, but he also helped raise two of her three other children.

“This person Metro lost was not just a regular officer,” the widow said. “He was one of the good ones.”

Contact Sabrina Schnur at sschnur@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0278. Follow @sabrina_schnur on Twitter.